- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1973 - Have a Change of Scene Page 3

1973 - Have a Change of Scene Read online

Page 3

But could such a thing happen to me?

‘You don’t have to volunteer,’ Jenny said. She seemed to know what was going on in my mind. ‘Why should you? Uncle Henry doesn’t think of details. I’ve said that before, haven’t I?’

‘Let’s get this straight,’ I said. ‘Are you telling me these kids - this Spooky - could threaten me if I worked with you?’

‘Oh yes, sooner or later, he will threaten you.’

‘Does his threat amount to anything?’

She crushed out her cigarette as she said, ‘I’m afraid it does.’

A change of scene?

I thought for a long moment. I suddenly became aware that during this talk with this woman I hadn’t once thought of Judy. This hadn’t happened since the crash. Maybe a kick in the face or even in the groin would make a change.

‘When do I start work?’ I said.

Her warm smile enveloped me.

‘Thank you - you start as soon as you have bought yourself a sweat shirt and jeans, and please don’t use that beautiful cigarette case.’ She got to her feet. ‘I have to go. I won’t be back until four o’clock. I’ll explain about the records and the card index system then - then you are in business.’

We went down the six flights of stairs to the street and I saw her into the cement-dusty Fiat 500. She paused before starting the engine.

‘Thank you for volunteering. I think we’ll make out.’ She regarded me for a moment through the tiny side window. ‘I’m sorry about your problem. It’ll come out all right - you have to be patient,’ and she drove away.

I stood on the ledge of the kerb, feeling cement dust settling over me and the humid heat turning the dust into gritty sweat. I liked her. As I stood there, I wondered what I was walking into. Did I scare easily? I didn’t know. It was when the crunch came that I would know.

I walked down the narrow, noisy street to Main Street in search of a pair of jeans and a sweat shirt.

I wasn’t aware when it happened, but it happened.

A dirty, ragged kid, around nine years of age, suddenly barged into me, sending me staggering. He pursed his lips and made a loud rude noise as he darted away.

It wasn’t until I got back to the Bendix Hotel that I found the back of my expensive jacket had been slashed by a razor blade and my gold cigarette case gone.

TWO

After I had changed into sweat shirt and jeans, I went along to the cop house to report the loss of the cigarette case. I found, a little to my surprise, I wasn’t fazed about losing it, but I knew Sydney would be devastated, and it was only fair to him to make an effort to get it back.

The charge room was thick with cement dust and the smell of unwashed feet. Sitting on a long bench against one of the walls were some ten kids: dirty, ragged and sullen. They regarded me with their small dark eyes as I walked up to the Desk Sergeant.

He was a vast hunk of human flesh with a face like a lump of raw beef. He was in shirt sleeves and sweat trickled down is face and into the creases of his thick neck, mingling with the cement dust. He was rolling a stub of pencil backwards and forwards on the blotter, and as I approached him, he raised himself slightly to break wind.

The kids on the bench giggled.

When I told him about losing the cigarette case he continued to roll the pencil backwards and forwards. Then he suddenly looked up and his pig eyes went over me with the intensity of a blowtorch.

‘You a stranger here?’ he asked. His voice was husky as if worn out with shouting.

I said I was a stranger here, that I had just arrived, that I was going to work with Miss Baxter, the welfare officer.

He pushed his cap to the back of his head, stared at his stub of pencil, sighed and produced a form. He told me to fill it in, then he continued to roll the pencil.

I filled in the form and returned it to him. Under the heading of ‘Value of article stolen’ I had put $1,500.

He read what I had written, then I saw his massive face tighten and pushing the form back to me, placing a dirty finger on the ‘Value of article stolen’ column, he demanded in his husky voice, ‘What’s this?’

‘That’s what the cigarette case is worth,’ I said.

He muttered something under his breath, stared at me, then at the form.

‘My jacket was slashed by a razor blade,’ I said.

‘That right? Your jacket worth fifteen hundred bucks too?’

‘The suit cost three hundred dollars.’

He released a snorting breath down his thick nostrils.

‘You got a description of the kid?’

‘Around nine years of age, dark, bushy hair, black shirt and jeans,’ I said.

‘See him there?’

I turned and looked at the row of kids. Most of them were dark with bushy hair: most of them were wearing black shirts and jeans.

‘Could be any one of them,’ I said.

‘Yeah.’ He stared at me. ‘You’re sure about the value of the case?’

‘I’m sure.’

‘Yeah.’ He rubbed the back of his sweaty neck, then put the form on the top of a pile of similar forms.

‘If we find it you’ll hear from us.’ A pause, then, ‘Staying long?’

‘Two or three months.’

‘With Miss Baxter?’

‘That’s the idea.’

He studied me for a brief moment, then a slow smile of contempt chased across his face.

‘Some idea.’

‘Don’t you think I’ll last that long?’

He sniffed, then began rolling the pencil again.

‘If we find it you’ll hear. Fifteen hundred bucks, huh?’

‘Yes.’

He nodded, then suddenly in a voice like a clap of thunder, he bawled, ‘Sit still, you little bastards, or I’ll get amongst you!’

I walked out, and as I reached the door I heard him say to another cop who was propping up one of the dirty walls, ‘Another nutter.’

It was now twenty after 13.00. I went in search of a restaurant, but there didn’t seem to be any restaurants in Main Street. I finally settled for a greasy hamburger in a bar, crowded with sweaty, dirt— smelling men who looked suspiciously at me and then away.

I then took a walk. Luceville had nothing to offer except dust and poverty. I walked around the district marked on Jenny’s map as section No. 5. I found myself in a world that I didn’t suspect existed. After Paradise City, this seemed to me to be a trip into Dante’s Inferno. I was immediately spotted as a stranger on every street. People moved away from me and some looked back and whispered about me. Kids whistled after me, and some made what is known as a loud rude noise. I walked until 16.00 and then made my way back to Jenny’s office. By that time I decided she must be quite a woman. To have spent two years in this hellhole and still be able to produce that warm, friendly smile was an achievement.

I found her at the desk, scribbling on a yellow form, and she looked up and there was the warm, friendly smile.

‘That’s better, Larry,’ she said, surveying me. ‘Lots better. Sit down and I’ll explain what I jokingly call my filing system. Can you handle a typewriter?’

‘I can.’ I sat down. I wondered if I should tell her about the cigarette case but decided not to. She had, according to her, plenty of problems without listening to mine.

We spent the next hour while she explained the system, showed me her reports and the card index and while this was going on the telephone bell rang ceaselessly.

A little after 17.00 she grabbed some forms and a couple of biros and said she had to go.

‘Shut up at six o’clock,’ she said. ‘If you could type out those three reports before you go.’

‘Sure. Where are you off to?’

‘The hospital. I have three old dears to visit. We open at nine in the morning. I may not be able to get in before midday. It’s my day for visiting the prison. Play it by ear, Larry. Don’t let them faze you. Don’t let them con you either. Give them nothing but advice. I

f they want anything tell them you will talk it over with me.’ With a wave of her hand she was gone.

I typed out the reports, broke them down and put them on cards, then filed them away. I was surprised and a little disappointed the telephone bell didn’t ring: it was as if it knew Jenny wouldn’t be there to answer it.

The evening lay before me. I had nothing to do except return to the hotel, so I decided I might as well stay on and get the filing system up-to-date. I have to admit I didn’t do much work. When I began to read the cards I got engrossed. The cards gave me a vivid picture of crime, misery, despair and pressure for money that held me like a top class crime novel. I began to realise what went on in section No. 5 in this smog-ridden town. When it got dark I turned on the desk light and went on reading. Time ceased to exist.

I was so engrossed I didn’t hear the door open. Even if I hadn’t been so engrossed I still mightn’t have heard it open. It was opened with stealth, inch by inch, and it was only when a shadow fell across the desk that I knew someone was in the room.

I was startled. That was, of course, the idea. With my nerves the way they were, I must have jumped six inches. I looked up, feeling my belly muscles tighten. I dropped the biro I was holding and it rolled under the desk.

I will always remember my first sight of Spooky Jinx. I didn’t know it was Spooky, but after I had described him to Jenny the following morning she told me that’s who it was.

Imagine a tall, very lean youth around twenty-two years of age. His shoulder length hair was dark, matted and greasy. His thin face was the colour of cold mutton fat. His eyes, like tiny black beads, dwelt closely either side of a thin, narrow nose. His lips were loose and red and carried a jeering little smile. He wore a yellow, dirty shirt and a pair of those way-out trousers with cat’s fur stuck to the thighs and around the bottoms. His lean but muscular arms were covered with tattoo designs. Across the back of each hand were obscene legends. Around his almost non-existent waist he wore a seven-inch wide belt, studded with sharp, brass nails: a terrible weapon if whipped across a face. From him came the acrid smell of dirt. I felt if he shook his head, lice would drop on to the desk.

I was surprised how quickly I got over my fright. I pushed back my chair so I could get to my feet. I found my heart was thumping, but I was in control of myself. My mind flashed back to the conversation I had with Jenny when she had warned me the kids in this district were vicious and extremely dangerous.

‘Hello,’ I said. ‘Do you want something?’

‘You the new hand?’ His voice was surprisingly deep which added to his menace.

‘That’s right. I’ve just arrived. Something I can do for you?’

He eyed me over. Beyond him I saw movement and I realised he wasn’t alone.

‘Bring your friends in unless they are shy,’ I said.

‘They’re fine as they are,’ he said. ‘You’ve been to the cop house, haven’t you, Cheapie?’

‘Cheapie? Is that you name for me?’

‘That’s it, Cheapie.’

‘You call me Cheapie. I call you Smelly, right?’

There was a suppressed giggle in the passage which was instantly hushed. Spooky’s tiny eyes lit up and became red beads.

‘A wise guy.’

‘That’s it,’ I said. ‘Makes two of us, doesn’t it, Smelly? What can I do for you?’

Slowly and deliberately, he unbuckled his belt and swung it in his hand.

‘How would you like this across your stinking face, Cheapie?’ he asked.

I shoved back my chair and stood up in one movement. I caught up the portable typewriter.

‘How would you like this in your stinking face, Smelly?’ I asked.

Only a few hours ago I wondered if I would scare easily. Now I knew. I didn’t.

We regarded each other, then slowly and with the same deliberation he buckled on the belt again and I with equal slowness and with equal deliberation, put down the portable typewriter.

We seemed to be back on square A.

‘Don’t stay long, Cheapie,’ he said. ‘We don’t like creeps like you. Don’t go to the cops again. We don’t like creeps going to the cops.’ He tossed a packet done up in greasy brown paper on the desk. ‘The stupid turd didn’t know it was gold,’ and he walked out, leaving the door open.

I stood there, listening, but they went as silently as they had come. This was a chilling experience.

They seemed deliberately to move like ghosts.

I undid the packet and found my cigarette case or what was left of it. Someone had flattened it into a thin, scratched sheet of gold - probably using a sledge hammer.

That night, for the first time since Judy had died, I didn’t dream of her. Instead, I dreamed of two ferret-like eyes sneering at me and a deep, threatening voice saying over and over again: Don’t stay long, Cheapie.

* * *

Jenny didn’t show up at the office until nearly midday. For the past hours I had been hard at work on the card index and I had got as far as letter H. The telephone rang five or six times, but each time the caller, a woman, mumbled she wanted to speak to Miss Baxter and had hung up. I had three visitors, all shabby elderly women who gaped at me, then backed away, also saying they wanted Miss Baxter. I gave them my brightest smile and asked if there was anything I could do, but they scuttled away like frightened rats. Around 10.30 while I was pounding the typewriter the door slammed open and a kid I immediately recognised as the kid who had stolen my cigarette case and had slashed my jacket blew me a raspberry and then dashed away. I didn’t bother to chase after him.

When Jenny arrived, her hair looking as if it would fall down any second, her smile was less warm and her eyes worried.

‘There’s bad trouble at the prison,’ she said. ‘They wouldn’t let me in. One of the prisoners went berserk. Two of the wardens have been hurt.’

‘That’s tough.’

She sat down and regarded me.

‘Yes.’ A pause, then she went on, ‘Is everything under control?’

‘Sure. You won’t recognise your system when you have time to look at it.’

‘Any trouble?’

‘You could call it that. I had a character here last night.’ I went on to describe him. ‘Mean anything to you?’

‘That’s Spooky Jinx.’ She lifted her hands and dropped them a little helplessly into her lap. ‘He’s quick off the mark. He didn’t bother Fred until he had been here two weeks.’

‘Fred? Your accountant friend?’

She nodded.

‘Tell me what happened,’ she said.

I told her, but I didn’t mention the cigarette case, I said Spooky had arrived and had told me not to stay long. I said we both made threatening gestures at each other, then he had left.

‘I warned you, Larry. Spooky is dangerous. You had better quit.’

‘How come you have remained here for two years? Hasn’t he tried to run you out?’

‘Of course, but he has his own odd code of honour. He doesn’t attack women, and besides, I told him he couldn’t scare me.’

‘He can’t scare me either.’

She shook her head. A strand of hair fell over her eyes. Impatiently, she pinned it back into place.

‘You can’t afford to be brave in this town, Larry. No, if Spooky doesn’t want you here, you have to go.’

‘You don’t really mean that, do you?’

‘For your sake, I do. You must go. I’ll manage. Don’t make things more complicated than they are. Please go.’

‘I’m not going. Your uncle advised a change of scene. Sorry to sound selfish, but I’m more concerned with my problem than with yours.’ I smiled at her. ‘Since I’ve arrived in this town I haven’t thought of Judy. That must be good. I’m staying.’

‘Larry! You could get hurt!’

‘So what?’ Then deliberately changing the subject, I went on, ‘I had three old girls here, but they wouldn’t talk to me: they wanted you.’

‘Please go

, Larry. I’m telling you Spooky is dangerous.’

I looked at my strap watch. It was now a quarter after midday.

‘I want to eat.’ I got to my feet. ‘I won’t be long. Is there any place in this town where I can get a decent meal? Up to now, I’ve been living on hamburgers.’

She regarded me, her eyes worried, then she lifted her hands in a gesture of defeat.

‘Larry, I do hope you realise what you are doing and what you’re walking into.’

‘You said you wanted help, that’s what you’re going to get. Don’t let’s get dramatic about it. How’s about a decent restaurant?’

‘All right: if that’s the way you want it.’ She smiled at me. ‘Luigi’s on 3rd Street: two blocks to your left. You can’t call it good, but it isn’t bad,’ then the telephone bell began to ring and I left her going through her ‘yes’ and ‘no’ routine.

After an indifferent meal - the meat was tough as old leather - I went around to the cop house.

There was a solitary kid sitting on the bench against the wall. He was around twelve years of age and he had a black eye. Blood dripped from his nose on to the floor. I looked at him and he looked at me. The hate in his eyes was something to see.

I went over to the Desk Sergeant, who was still rolling his pencil backwards and forwards while he breathed heavily through his nose. He looked up.

‘You again?’

‘To save you trouble,’ I said, not bothering to keep my voice down because I was sure the kid, sitting on the bench, was a member of Spooky’s gang, ‘I have my cigarette case back.’ I laid the flattened strip of gold on the sergeant’s blotter.

He regarded what was left of it, picked it up, turned it in his big sweaty hands, then put it down.

‘Spooky Jinx returned it to me last night,’ I said.

He stared down at the battered strip of gold.

I went on in a deadpan voice, ‘He said they didn’t realise it was gold. You can see what they have done with it.’

He squinted at the flattened metal, then released a snort down his nose.

‘Fifteen hundred bucks, huh?’

‘Yes.’

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

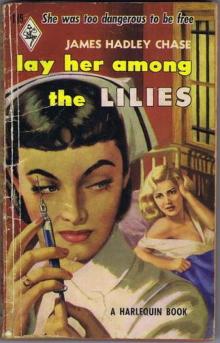

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

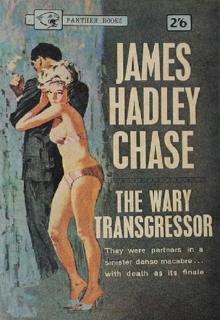

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

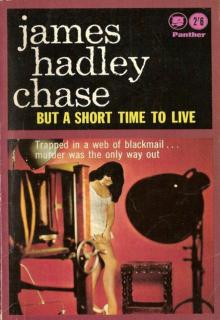

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail