- Home

- James Hadley Chase

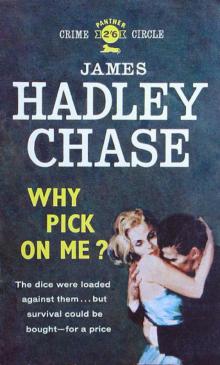

Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? Read online

James Hadley Chase

Why Pick On Me ?

1951

Synopsis

Milly Lawes a Piccadilly streetwalker, found a strange ring in her room one day. An hour later she was dead, and the ring gone. Scotland Yard knew all about the ring though; so did the Secret Service, and before very long, did Martin Corridon, ex-Commando, ex-M15, ex-ethics of any kind . . . Corridon didn't really want to know, didn't want to work with the service again, but Milly had been a sort of friend, and the thought of her cut throat and blood soaked bed was enough to send him off on a trail of sabotage and murder. A trail that had him running as a hunter, and hunted . . .

Table of Contents

Synopsis

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

CHAPTER ONE

I

Corridon moved through the haze of tobacco smoke that hung over the strident red and yellow room, oblivious of the sudden hushed voices, the quick turning of heads, the furtive lifting of a thumb, jerking in his direction.

He was used to being stared at and whispered about wherever he went in Soho. He carried his reputation with him like a leper carries his bell.

He knew he was envied and distrusted; envied for his strength and his callous indifference to danger. Even now, six years after the event, his war record was still talked about. A man who could do what he did, they said of him, could do anything.

His reputation served him as study serves a doctor, a lawyer or an engineer: it was his livelihood. Whenever there was an off-coloured job to be done, it was offered to him. Those who hadn’t the courage to risk their own skins hired him to do the job for them. His terms were invariably the same: half down and the rest when the job is done. More often than not, he took half the promised amount and then refused to do the job. “You can always sue,” he would say, and smile at them. But they couldn’t sue. The jobs ware not the kind you took before a judge.

It was astonishing how long this racket lasted. No one likes to advertise he has been outsmarted, and Corridon relied on that fact. The men he swindled kept a tight-mouthed silence. Corridon continued to listen to the various propositions, make his terms, accept the first payment, and then welsh. He had no qualms of conscience. For five years he had lived in a world of grafters, rogues, crooks, and thieves. He regarded himself cynically as a major parasite living on a hest of minor parasites. They didn’t have to come to him, but their fear, their greed and their dull-witted stupidity forced them to enlist his aid and, once in his hands, they were helpless.

But it couldn’t last indefinitely. Corridon knew that. Sooner or later the word would get round. Sooner or later two or three of these men would confide in each other and then they would realize the ramifications of Corridon’s racket. They would find that their cases weren’t isolated ones, that Solly and Lew and Petey and a host of others had also been caught and skinned. Then the word would go around, and the door would be slammed in his face, and he would have to think of a new method of making money.

The word was going round. A month had drifted by without anyone approaching him, and as the days passed, the bundle of pound notes Corridon carried around with him grew slimmer. He had fifteen pounds in his pocket this night: the smallest amount of money he had carried since leaving the Army.

But it didn’t worry him. Nothing worried Corridon. He believed that his destiny ran in a straight line: it had a beginning and an ending: what happened between these two points was something he had no wish to control. He found it more satisfactory to know that the shape of his life was given over to chance, and that he himself was nothing more than an interested spectator. He knew he could alter his destiny if he wished, but he wasn’t interested enough in himself to bother. He preferred to drift, allowing outside influences, unexpected opportunities and people – particularly people – to weave the foreground of his future.

This night, from sheer boredom, Corridon had come to the Amethyst Club, one of the shadiest night clubs in Soho, in the hope that something would happen to shift him off the sandbank of inactivity into the swiftly-moving current of his previous month’s existence.

Zani owned the Amethyst Club. Immaculate in a dark blue tuxedo, his dark negroid features set in a heavy frown, he stood behind the S-shaped bar, his thick, fat fingers drumming soundlessly on the polished wood.

He watched Corridon sit down behind a table in a dimly-lit corner of the room, and his frown deepened. He didn’t want Corridon in his club. He had heard that Corridon was running short of money, and he imagined Corridon would ask him for a loan. He had already decided it would be unwise to refuse. Corridon had an unpleasant way of reacting to a refusal of money. Generous himself, lending carelessly to whoever asked him, never bothering about repayment, Corridon expected similar treatment. He had never asked Zani for a loan, but Zani was sure, before very long, he would, and Zani hated parting with money.

Corridon pushed his hat to the back of his head and looked around the red and yellow room. There were about thirty men and women in the club: some of them sitting on stools up at the bar, some at the glass-topped tables scattered about the room, some stood in the doorway, all were drinking, smoking and talking.

They paid no further attention to him after he had sat down, and he grinned jeeringly, remembering the nights when they had crowded round him, offering him drinks, trying to attract his attention, wanting to display their friendship with him as a mark of their own importance.

Corridon didn’t mind being ignored. It amused him. But their indifference to him was a warning light. He would have to break fresh ground, not by making an effort, that he refused to do, but by moving to a new district, by displaying himself in an unworked territory, by meeting new people and by dangling his reputation before them as an angler dangles a baited hook.

But where? He rubbed his heavy jaw thoughtfully. Hammersmith? He grimaced. That would be going down a step or two. Perhaps it might be an idea to try Birmingham or Manchester. There were plenty of racketeers waiting to be fleeced in the North, but the prospects didn’t appeal to him. If he were going to change his ground, he might as well go to some place where he would be happy: he knew he would never be happy in the grime and wet of Manchester.

Paris then.

He lit a cigarette and beckoned to a waiter.

Yes, Paris. He hadn’t been to Paris for six years. Next to London, he liked Paris more than any other capital in the world. He knew a lot of people in Paris. He knew his way around. He knew where to make the necessary connections.

But first, he would have to raise some money. It was useless to go to Paris without money. He would have to support himself for several weeks before he could hope to entice anyone on to his hook. He would have to live in style, too. The bigger the show, the bigger the sucker. He would need at least a couple of hundred pounds.

The waiter stood at his side.

“A large whisky and water,” he ordered, then catching sight of Milly Lawes moving through the crowd towards him, he went on, “Make that two.”

Milly was twenty-six, blonde, fragile and pretty. Her china-blue eyes were vacant, her wide, painted mouth set in a perpetual smile. She had a baby-daughter, no husband, and walked the streets for a living. Corridon had known her off and on for two years. He approved of her devotion to her daughter, excused her profession, and lent her money when she was hard up.

“Hello, Martin,” she said, pausing at his table. “Busy?”

He looked up at her and shook his head.

“There’s a drink coming for you,” he sai

d. “Want to sit down?”

She glanced over her shoulder, aware that she was being watched.

“Do you mind, darling?”

“Don’t call me that,” Corridors said irritably. “And sit down. Why should I mind?”

She sat down, laying her umbrella and bag under her chair. She was wearing a grey flannel two-piece suit that showed off her figure. He thought she looked smart and neat enough to take to the Ritz.

“How’s business, Milly?”

She pulled a little face, then laughed.

“It’s not bad. Not really. Not like it was, of course. It’s the Americans I miss.”

The waiter set the drinks on the table and Corridors paid. Milly, who missed nothing, raised her eyebrows at the slimness of his roll.

“And you, Martin?”

He shrugged.

“So, so. How’s Susie?”

Milly’s face lit up.

“Oh, she’s fine. I’m going down on Sunday to see her. She’s beginning to talk.”

Corridon grunted.

“Now she’s started, she’ll never stop,” he said. “Send her my love.” He felt in his pocket, separated a note from his roll, screwed it up in his hand and dropped it into her lap. “Buy her something. Kids like presents.

“But Martin, you want this. I’ve heard…”

“Never mind what you’ve heard.” The grey eyes hardened. “Do what you’re told and shut up.”

“Yes, darling.”

Over in the far corner, Max, a skinny little man in a red and white check shirt and baggy flannel trousers began to play the piano.

Max had been with the club since it opened. It was rumoured he had T.B., cancer, or an inoperable tumour, but he had neither confirmed nor denied the rumour. He hadn’t served during the war, but had sat at the piano, playing hour after hour, night after night, without rest, explaining it was a penance for being so useless.

Milly began to hum the tune he was playing, tapping her high heels in time with the steady, infectious rhythm.

“Isn’t he a lovely player?” she said. “I wish I could do something really well. Fancy being able to play like that.”

Corridon grinned.

“Don’t underrate your talents, Milly. Max would be glad to earn half what you do.”

She grimaced.

“I want to show you something, Martin. Keep it out of sight.” She picked up her bag, opened it, dipped into it and dropped a small object into his hand. “Know what it is?”

Under cover of the table, Corridon examined what she had given him. It was a piece of white stone, in the shape of a ring, the top side being flat. He frowned at it, turning it over in his hand. Then he glanced up, looking at Milly sharply.

“Where did you find it, Milly?”

“Oh, I picked it up.”

“Where?”

“What is it, Martin? Don’t be mysterious.”

“I don’t know for certain. It’s jade, and it’s my bet it’s an archer’s thumb ring.”

“A – what?”

“The Chinese used to make them. I should say this is a fake. I don’t know, but if it isn’t, it’s worth money.”

“How much?” Milly’s face was tense.

“No idea. A hundred perhaps. I don’t know. Probably more.”

“You mean archers used to wear a ring like that?”

“Yes. They used it to draw the bow-string. If this isn’t a fake, it’s around 200 B.C.”

Milly’s face was a study.

“B.C.?”

Corridon grinned at her.

“Don’t get excited. It’s probably a copy. Where did you find it?”

“One of my gentlemen friends must have dropped it,” Milly said cautiously. “I picked it up under the chest of drawers.”

“Better turn it over to the cops, Milly,” Corridon said. “If it’s genuine, he’ll report it missing. I don’t want you to go to jail.”

“He doesn’t know I’ve got it,” Milly said.

“He soon will, if you try to sell it.”

Milly held out her hand and Corridon passed the ring back to her under the table.

“Think he’ll offer a reward?”

“He might.”

She thought about this, then shook her head.

“I’ve got a hope. If it’s worth anything, the busies wouldn’t give me the reward. I know them. They’d pretend they had found it themselves.”

Corridon thought that was likely, but he didn’t say so.

“Better get rid of it, Milly. It could be very easily traced.”

“You wouldn’t like to buy it, would you, Martin? You could have it for – for fifty.”

Corridon laughed.

“It’s probably worth a fiver. No, thanks, Milly, it’s not in my line. I wouldn’t know where to place it. If it’s genuine, it’s too hot. If it isn’t, it’s not worth bothering about.”

Milly put the ring back in her bag with a disappointed sigh.

“Oh, well. I’ll do something about it. Think Zani would give me anything for it?”

“Not a hope. He’d probably turn you in.”

“I didn’t know it was jade. I didn’t know you could get white jade. I thought it was yellow.”

“You’re thinking of amber,” Corridon said patiently.

“Am I?” Milly looked vague. “Oh, well, I suppose I am. I don’t know how you know all these things. As soon as I saw it I knew you could tell me what it was.”

“If you went to the British Museum sometimes,” Corridon said with his jeering smile, “you’d know about things too.”

“Oh, I’d die of boredom.” She picked up her umbrella. “Catch me in the British Museum. Well, I’d better get along. Thanks for Susie’s present. I’ll get her a Mickey Mouse.”

“Good idea.” Corridon stubbed out his cigarette. “And don’t forget to get rid of that ring. Give it to the first copper you see and tell him you picked it up.”

Milly giggled.

“I believe I will: just to see his face when I give it to him. So long, Martin.”

“So long.”

Later in the evening, Corridon left the Amethyst Club much to Zani’s surprised relief without asking for a loan. The idea never entered Corridon’s head. He walked to his garage flat in Grosvenor Mews.

On his way, he saw Milly standing at the corner of Piccadilly and Albermarle Street. She was talking to a slightly-built man in a dark overcoat and hat. Corridon glanced at her as he passed, but she didn’t see him. She took the man’s arm, and together they walked up Albermarle Street towards her second-floor flat.

Corridon hadn’t given her companion more than a quick, indifferent glance. He was at that moment occupied with his plans for the future. Usually he was extremely observant, and had he been concentrating, he would have been able to retain in his memory a detailed picture of the man. As it was, his mind wrestling with his own problems, the man was no more to him than a featureless, shadowy figure.

II

For a year now Corridon had lived in a three-room flat over a garage behind St. George’s Hospital. A woman came in every day to keep it clean, and Corridon had his meals out. He scarcely ever used the small, shabbily-furnished sitting-room. It was damp and dark and noisy.

The bedroom, also damp and dark, overlooked a high wall that shut out the light and ran with water when it rained. But Corridon didn’t care. He had no wish to make it a home. He had few clothes, no possessions worth bothering about, and could leave the flat at a moment’s notice, never to return.

As a place to sleep in, it served its purpose, and it had several advantages. It was near the West End. It had bars to every window, and a solid front door. The rooms over the other garages were used by commercial firms who moved out at six o’clock each night, and left Corridon the sole survivor of the long, silent mews.

He woke at eight o’clock the following morning, frowned up at the ceiling as his mind immediately took up the problem of raising sufficient capital to leave E

ngland.

He was still examining ideas, discarding most of them, as he finished shaving and began to dress. Two hundred pounds! Six months ago it would have been easy. It seemed an impossibility now.

As he fastened his tie, there came a heavy rap on the front door knocker. He went down the steep stairs that led directly to the only entrance to the flat and opened the door, expecting to find the postman. Instead, he found himself looking into the beaming face of Detective-Inspector Rawlins, C.I.D.

“Good morning,” Rawlins said. “Just the fella I want to see.”

Rawlins was a big, red-faced man in his late forties. He always managed to look as if he had just come from a fortnight’s holiday at the seaside, and even after working non-stop for sixty hours he appeared to be exuding energy, good health, and a rather overpowering jolliness. Corridon knew him to be a courageous, hard-working, conscientious policeman, scrupulously fair, but tricky. A man who cloaked a swift working mind with the beaming smile of a country parson.

“Oh, it’s you,” Corridon said, scowling. “What do you want?”

“Had breakfast yet?” Rawlins asked. “I’ll have a cup of tea with you if you’re just going to start.”

“Come in then,” Corridon said. “It won’t be tea; it’ll be coffee, and if you don’t like it, stay out.”

Rawlins followed him up the steep stairs and entered the dark flute sitting-room. While Corridon added another cup and saucer and a plate to the already laid table, Rawlins moved about the room, whistling softly under his breath, his eyes missing nothing.

“Can’t understand why you live in a hole like this,” he said. “Why don’t you get yourself something more comfortable?”

“It suits me,” Corridon returned, pouring the coffee. “I’m not one of your home-loving types. How’s the wife?”

“She’s fine.” Rawlins sipped the coffee and grunted. “I expect she’s wondering where I’ve got to. Not much of a life being a copper’s wife. Still, she’s used to it by now.”

“Fine excuse for you to spend a night on the tiles,” Corridon returned, lighting a cigarette and flopping on the settee. He stirred his coffee while he eyed Rawlins thoughtfully. Rawlins hadn’t come here to pay a social call. Corridon knew that. He was curious to know why he had come at this hour.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

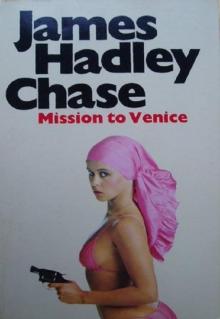

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

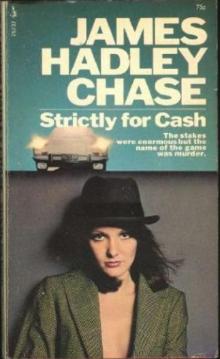

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

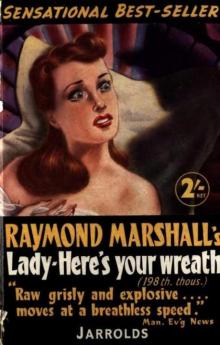

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

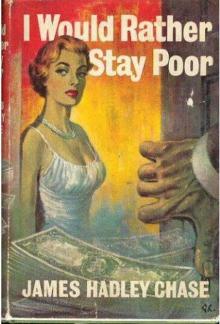

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

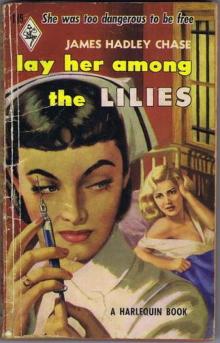

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

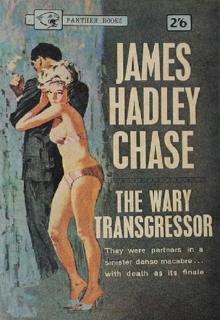

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

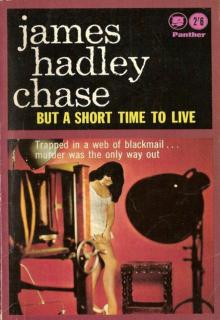

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail