- Home

- James Hadley Chase

No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine Read online

No Business Of Mine

James Hadley Chase

NO BUSINESS OF MINE

COPYRIGHT © 1947

This book is for, my friend, Philip Lukulay,

who always cheated me in hand-tennis, and I

was always forgiving . . .

I would personally like to thank Mr. Cliff from London

who sent me a copy of this novel and “More Deadly

Than The Male.”

Thank You very much . . .

NO BUSINESS OF MINE

By

JAMES HADLEY CHASE

ROBERT HALE LIMITED

63 Old Brompton Road London S.W.7

Chapter I

MY name is Steve Harmas and I am a Foreign Correspondent of

the New York Clarion. During the years 1940-45 I lived in the Savoy

Hotel with a number of my colleagues and told the people of America

the story of Britain at war. I gave up the cocktail bar and the comfort

of the Savoy when the Allied Armies invaded Europe. To get me to go

was like peeling a clam off a wall, but my editor kept after me, and

finally I went. He told me the experience would give me character. It

gave me a pain you-know-where, but it didn’t give me character.

After the collapse of Germany, I felt I had had enough of war and

hardship, and I changed places with a colleague without him knowing

anything about it, and returned to America and two-pound steaks on

his ticket.

Several months later I was offered an assignment to write a series

of articles on post-war Britain. I didn’t particularly want the job: there

was a whisky shortage in England at the time, but there was a girl

named Netta Scott who used to live in London when last I was there,

and I did want to see her again.

I don’t want you to get me wrong about Netta Scott. I wasn’t in

love with her, but I did feel I owed her a great deal for giving me such

a swell time while I was a stranger in a strange country, and quite

unexpectedly I found myself in the position to do so.

It happened like this: I was reading the sporting sheet on my way

to the office, still in two minds about going to England, when I noticed

that one of the horses running in the afternoon’s race was named

Netta. The horse was a ten to one outsider, but I had a hunch and

decided to back it. I laid out five hundred dollars, and sat by the radio

with butterflies in my stomach, awaiting the result.

The horse won by a nose, and there and then I decided to split the

five-thousand-dollar winnings with Netta: I caught the first available

plane to England.

I got a big bang out of imagining Netta’s reaction when I walked in

on her and planked down before her five hundred crisp, new one

pound notes. She had always liked money, always grumbled about

being hard up, although she would never let me help her once we got

to know each other. It would be a great moment in her life, and it

would square my debt at the same time.

I first met Netta in 1942 at a luxury night club in Mayfair’s Bruton

Mews. She worked there as a dance hostess, and don’t let anyone kid

you dance hostesses don’t work. They develop more muscles than

Strangler Lewis ever had by warding off tired business men who are

not as tired as all that. Her job was to persuade suckers like me to buy

lousy champagne at five pounds a bottle, and to pay her ten shillings

for the privilege of dancing her around a floor the size of a pocket

handkerchief.

The Blue Club, as it was called, was run by a guy named Jack

Bradley. I had seen him once or twice, and I thought then he looked a

doubtful customer. The only girl working in the club who wasn’t

scared of him was Netta: but Netta wasn’t scared of any man.

The story goes that all the girls had to do a night shift with Bradley

before they could qualify for the job of hostess. They told me that

Netta and Bradley spent the night reading the illustrated papers when

she qualified, but that was only after she had blunted his glands by

wrapping a valuable oil painting around his thick neck. I don’t know

whether the yarn was true: Netta wouldn’t talk about it, but knowing

her, I’d say it was.

Bradley must have made a packet out of the club. It was

patronized almost entirely by American officers and newspaper men

who had money to burn. They burned it all right in the Blue Club. The

band was first class, the girls beautiful and willing, and the food

excellent; but the cost was so high you had to put on an oxygen mask

before you looked at the bill.

Netta was one of twelve girls, and I picked her out the moment I

saw her.

She was a cute trick: a red head with skin like peaches and cream.

Her curves attracted my attention: curves always do. They were a blue

print for original sin. I’ve seen some female hairpin bends in my time,

but nothing quite in Netta’s class. As my companion, Harry Bix, a hard-

bitten bomber pilot, put it, “A mouse fitted with skis would have a

grand run down her, and would I like to be that mouse!”

Yes, Netta was a cute trick. She was really lovely in a hard,

sophisticated way. You could tell right off that she knew her way

around, and if you hoped to get places with her it was gloves off and

no holds barred; even at that she’d probably lick you.

It took some time before Netta thawed out with me. At first she

considered me just another customer, then she regarded me with

suspicion, thinking I was on the make, but finally she accepted the

idea that I was a lonely guy in a strange city who wanted to make

friends with her.

I used to go to the Blue Club every evening. After a month or so

she wouldn’t let me buy champagne, and I knew I was making

progress. One night she suggested we might go together to Kew

Gardens on the following Sunday and see the bluebells. Then I knew

I’d got somewhere with her.

It finally worked out that I saw a lot of Netta. I’d call for her at her

little flat off the Cromwell Road and drive her to the Blue Club.

Sometimes we’d have supper together at the Vanity Fair; sometimes

she’d come along to the Savoy and we’d dine in the grill-room. She

was a good companion, ready to laugh or talk sense depending on my

mood, and she could drink a lot of liquor without getting tight.

Netta was my safety-valve. She bridged all the dreary boredom

which is inevitable at times when one is not always working to

capacity. She made my stay in London worth remembering. We finally

got around to sleeping together once or twice a month, but as in

everything we did, it was impersonal and didn’t mean a great deal to

either of us. Neither she nor I were in love with each other. She never

let our association get personal, although it was intimate enough.

That is she never asked me about my home, whether I was married,

what I i

ntended to do when the war was over; never hinted she would

like to return to the States with me. I did try to find out something

about her background, but she wouldn’t talk. Her attitude was that

we were living in the present, any moment a bomb or rocket might

drop on us, and it was up to us to be as happy as we could while the

hour lasted. She lived in a wrapping of cellophane. I could see and

touch her, but I couldn’t get at her. Oddly enough this attitude suited

me. I didn’t want to know who her father was, whether she had a

husband serving overseas, whether she had any sisters or brothers. All

I wanted was a gay companion: that was what I got.

We kept up this association for two years, then when I received

orders to sail with the invading armies we said good-bye.

We said good-bye as if we would meet again the next evening,

although I knew I wouldn’t see her for at least a year, perhaps never

see her again: she knew it too.

“So long, Steve,” she said when I dropped her outside her flat.

“And don’t come in. Let’s say good-bye here, and let’s make it quick.

Maybe I’ll see you again before long.”

“Sure, you’ll see me again,” I said.

We kissed. Nothing special: no tears. She went up the steps, shut

the door without looking back.

I had planned to write to her, but I never did. We moved so fast

into France and things were so hectic that I didn’t have the chance to

write for the first month, and after that I decided it was best to forget

her. I did forget her until I returned to America. Then I began to think

of her again. I hadn’t seen her for nearly two years, but I found I could

remember every detail of her face and body as clearly as if we had

parted only a few hours ago. I tried to push her out of my mind, went

around with other girls, but Netta stuck: she wouldn’t be driven away.

So when I spotted that horse, backed it and won, I knew I was going to

see her again, and I was glad.

I arrived in London on a hot August evening after a long,

depressing trip down from Prestwick. I went immediately to the Savoy

Hotel where I had booked a reservation, had a word with the

reception clerk who seemed pleased to see me again, and went up to

my room, overlooking the Thames. After a shower and a couple of

drinks I went down to the office and asked them to let me have five

hundred one pound notes. I could see this request gave them a jar,

but they knew me well enough by now to help me if they could. After

a few minutes delay they handed over the money with no more of a

flourish than if it had been a package of bus tickets.

It was now half-past six, and I knew Netta would be home at that

hour. She always prepared for the evening’s work around seven

o’clock, and her preparations usually took the best part of an hour.

As I was waiting in a small but select queue for a taxi, I asked the

hall porter if he knew whether the Blue Club still existed. He said it

did, and that it had now acquired an unsavoury reputation as it had

installed a couple of doubtful roulette tables since my time.

Apparently it had been raided twice during the past six months, but

had escaped being closed down through lack of evidence. It seemed

Jack Bradley managed to keep one jump ahead of the police.

I eventually got a taxi, and after a slight haggle, the hall porter

persuaded the driver to take me to Cromwell Road.

I arrived outside Netta’s flat at ten minutes past seven. I paid off

the driver, stood back, and looked up at her windows on the top floor.

The house was one of those dreary buildings that grace the back

streets off Cromwell Road. It was tall, dirty, and the lace curtains at

the windows were on their last legs. Netta’s flat, one of three, still had

the familiar bright orange curtains at the windows. I wondered if I was

going to walk in on a new lover, decided I’d chance it. I opened the

front door, began the walk up the three flights of coco-nut-matted

stairs.

Those stairs brought back a lot of pleasant memories. I

remembered the nights we used to sneak up them, holding our shoes

in our hands lest Mrs. Crockett, the landlady who lurked in the

basement, should hear us. I remembered too, the night I had flown

over Berlin with a R.A.F. crew and had arrived at Netta’s flat at five

o’clock in the morning, too excited to sleep and wanting to tell her of

the experience, only to find she hadn’t come home that night. I had

sat on the top of those stairs waiting for her, and had final y dozed off,

to be discovered by Mrs. Crockett, who had threatened to call the

police.

I passed the doors of the other two flats. I had never discovered

who lived in them. During the whole time I had visited Netta I hadn’t

once seen the occupiers. I arrived, a little breathless, outside Netta’s

front door, and paused before I rang the bell.

Everything was exactly the same. There was her card in a tiny

brass frame screwed to the panel of the door. There was the long

scratch on the paint-work which I had made when slightly drunk with

the latchkey. There was the thick wool mat before the door. I found

my heart was beating a shade quicker, and my hands were a little

damp. It seemed to me all of a sudden that Netta had become

important to me: I’d been away too long.

I punched the bell, waited, heard nothing, punched the bell again.

No one answered the door. I continued to wait, wondering if Netta

was in her bath. I gave her a few more seconds, punched the bell

again.

“There’s no one there,” a voice said from behind me.

I turned, looked down the short flight of stairs. A man was

standing in the doorway of the lower flat, looking up at me. He was a

big strapping fellow around thirty, broad and well-built but far from

muscular. With a frame like a hammer-thrower, he was yet soft, just

this side of fat. He stood looking up at me with a half-smile on his

face, and the impression he gave me was that of an enormous sleepy

tom-cat, indifferent, self-sufficient, pleased with himself. The waning

sunlight coming through the grimy window caught the gold in his

mouth, making his teeth come alive.

“Hello, baby,” he said. “You one of her boy friends?” He had a

faint lisp, and his corn-coloured hair was cut close. He was wearing a

yellow and black silk dressing-gown, fastened at his throat; his pyjama

legs were electric blue, his sandals scarlet. He was quite a picture.

“Go jump into a lake,” I said. “Jump into two if one won’t hold

you,” and I turned back to Netta’s door.

The man giggled. It was an unpleasant hissing sound and for no

reason at all it set my nerves jumping.

“There’s no one there, baby,” he repeated, then added in an

undertone, “she’s dead.”

I stopped ringing the bell, turned, looked at him. He raised his

eyebrows, and his head waggled from side to side ever so slightly.

“Did you hear?” he asked, and smiled as if he were privately amused

at some s

ecret joke of his own.

“Dead?” I repeated, moving away from the door.

“That’s right, baby,” he said, leaning against the door-post, giving

me an arch look. “She died yesterday. You can still smell the gas if you

sniff hard enough.” He touched his throat, flinched. “I had a bad day

with it yesterday.”

I walked down the stairs, stood in front of him. He was an inch

taller than I and a lot broader, but I knew he hadn’t any iron in his

bones.

“Calm down, Fatso,” I said, “and give it to me straight. What gas?

What are you raving about?”

“Come inside, baby,” he said, smirking. “I’ll tell you about it.”

Before I could refuse, he had sauntered into a large room which

stank of stale scent and was full of old, dusty furniture.

He dropped into a big easy chair. As his great body dented the

cushions a fine cloud of dust arose.

“Excuse the hovel,” he said, looking around the room with an

expression of disgust on his face. “Mrs. Crockett’s a slut. She never

cleans the place and I can’t be expected to do it, can I, baby? Life’s too

short to waste time cleaning when one has my abilities.”

“Never mind the Oscar Wilde act,” I said impatiently. “Are you

telling me Netta Scott’s dead?”

He nodded, smiled up at me. “Sad, isn’t it? Such a delightful girl;

beautiful, lovely little body; so ful of vigour — now, just meal for the

worms.” He sighed. “Death is a great level er, isn’t it?”

“How did it happen?” I asked, wanting to take him by his fat

throat and shake the daylights out of him.

“By her own hand,” he said mournfully. “Shocking business. Police

rushing up and down stairs . . . the ambulance . . . doctors . . . Mrs.

Crockett screaming . . . that fat bitch in the lower flat gloating . . . a

crowd in the street, hoping to see the remains quite, quite ghastly.

Then the smell of gas — couldn’t get it out of the house all day.

Shocking business, baby, really most, most shocking.”

“You mean she gassed herself?” I asked, going cold.

“That’s right, the poor lamb. The room was sealed with adhesive

tape . . . roll upon roll of adhesive tape, and the gas oven going full

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

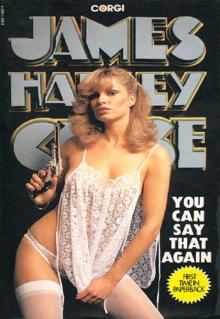

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

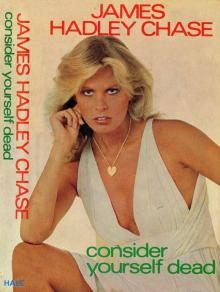

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

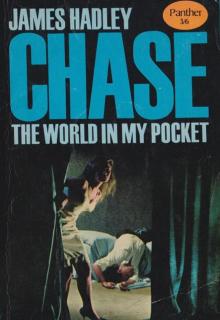

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

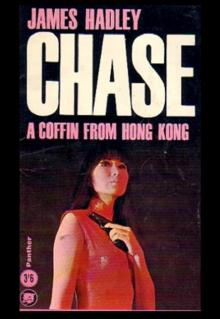

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

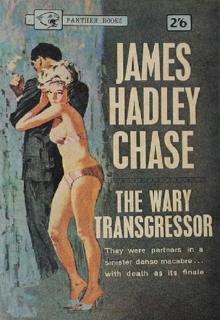

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

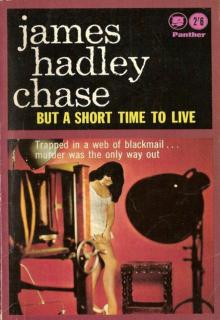

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

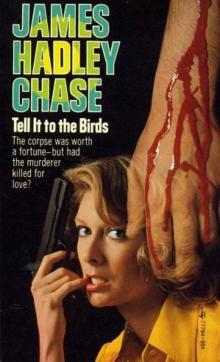

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

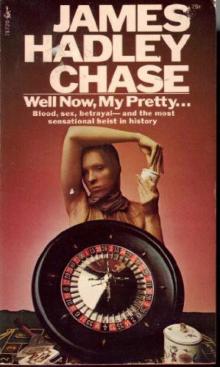

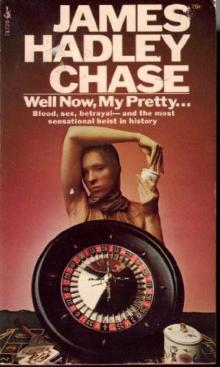

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

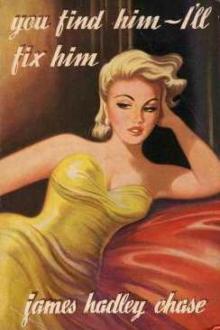

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

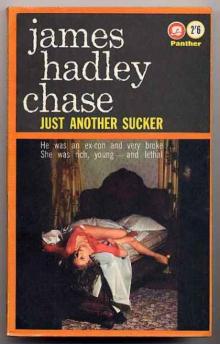

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

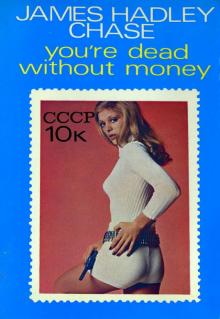

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

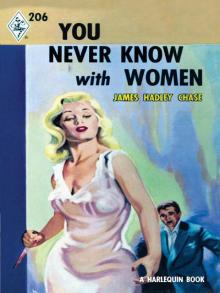

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

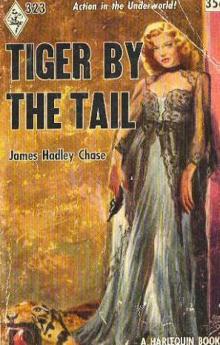

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail