- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf Read online

Table of Contents

chapter one

chapter two

chapter three

chapter four

chapter five

chapter six

chapter seven

chapter eight

Hand Me a Fig Leaf

James Hadley Chase

1981

chapter one

The intercom buzzed.

Chick Barley, who was having his second drink of the morning, slopped some Scotch from his glass, cursed, then thumbed down the switch.

Glenda Kerry's voice came out of the box in a loud and metallic squawk.

"Dirk to the Colonel, and pronto!" she snapped and cut the connection.

Chick looked over at me at my desk.

"You heard the lady! The trouble with that chick is she isn't getting it regularly. When a chick doesn't. . .”

But I was on my way, pounding down the long corridor to Colonel Victor Parnell's office.

I had been with the Parnell Detective Agency for exactly a week. The agency, the best and most expensive on the Atlantic coast, was located on the top floor of the Truman building on Paradise avenue, Paradise City, Florida. The agency catered for the rich and the plush and I was still in awe of the luxury atmosphere the set-up exuded.

Colonel Parnell, a veteran of the Vietnam war, with money inherited from his father had set up the agency some five years ago and had made an instant success. He employed twenty operators, most of them ex-cops or ex-military policemen who worked in pairs. I was a replacement and was lucky to be paired with. Chick Barley, a massively built, sandy-haired ex-military police lieutenant, regarded as Parnell's best operator.

I was lucky to have got the as the competition was fierce. I only got it because my father, in the past, had done Parnell a favour. I never knew just what he did do for Parnell, but the colonel wasn't a man to forget.

For, the past thirty years, my father had run the Wallace Investigators' Service in Miami, specializing in divorce work. After I had gone through college, I joined the firm, and for ten years had worked as an investigator. My father had taught me all he knew, which was plenty, but finally old age caught up with him and he decided to retire. By then the agency was way downhill. At one time, he had employed three operators, plus me. By the time he decided to retire, I was the only operator and had little or nothing to do.

Colonel Parnell was looking for a replacement for one of his operators who had turned crooked. My father wrote to him, suggesting he could do worse than employ me. The interview went well and now I was working for the Parnell Agency, a big step up from the defunct agency my father ran, and which he closed down when I left for Paradise City.

As a new boy, I had had a week, working with Chick on a self-service store theft. It had been a dull assignment, but most operators expect dull assignments: either wife-watching or husband-watching or trying to trace missing people and what have you. To be a successful operator you have to have patience, toughness and an inquiring mind. I had all these, plus ambition.

Parnell worked closely with the Paradise City police. If there was any suspicion that the assignment he was given was criminal, he would alert Chief of Police Terrell. Working this way, he had full cooperation with the police and, for an operator, this was important.

There were other much more important assignments with the rich that the police knew nothing about: blackmail, daughters running off with no-gooders, drunken wives, homosexual sons and so on: assignments kept secret and here Parnell made big money. The rich came to him and revealed, in confidence, the skeletons in their cupboards. I had heard about this from Chick. Sooner or later, he told me, I would be promoted to the upper echelon to help the rich cover up their murky problems.

I tapped on Parnell's door, waited a moment, then walked into the spacious, comfortably furnished office, so unlike the dark, gloomy little room from which my father operated.

Parnell was looking out of the big window that gave onto Paradise avenue, the sea and the miles of beach. He turned.

Parnell was a giant of a man, on the wrong side of sixty. His fleshy sun-tanned face, small piercing blue eyes and the rattrap of a mouth stamped him as a veteran soldier, and don't-let-us-forget-it.

"Come in, Dirk," he said. "Sit down." He went to his desk and lowered his bulk into the big executive chair. "How are you settling in?"

I found a chair and sat on the edge of it. Parnell made me nervous. Even Chick, who had worked with him for years, admitted that he was also nervous in Parnell's presence.

"Fine, sir," I said.

"Chick tells me you are useful. You should be. Your father was a good operator. You've come from a good school."

"Thank you, sir."

"I've a job for you. Read this," and he pushed a letter across his desk towards me.

The letter was written in a sprawling handwriting and the paper was slightly soiled as if written on a dirty desk or table.

Alligator Lane

West Creek.

Dear Colonel Parnell,

When my son was killed in battle, you were good enough to write to me, telling me how he died, and that you had recommended him to be awarded the Medal of Honor which was grated to him posthumously.

I understand you have a Detective Agency in Paradise city, not far from where I live. I need a detective. My grandson has disappeared. The local police show no interest. I must know what has happened to the boy. I enclose one hundred dollars to hire one of your men to find the boy. I am unable to pay more, but rely on you to do this for me because of what my son did for your regiment.

Yours faithfully,

Frederick Jackson.

Having talked to Glenda Kerry, who looked after the financial end of the agency together with Charles Edwards, the accountant, I knew the agency never took on a client who wasn't prepared to pay at least $5000 as a retainer, and $1000 a day expenses: I looked at Parnell and raised my eyebrows.

"Yup!" Parnell said, reading my thoughts. "We get a few letters like this, asking to hire operators: people with no money, and Glenda gives them a polite brush-off, but this is different." He paused to light a cigar. Then he went on, "Ever heard of Mitch Jackson?"

"Yes, sir."

I had only a vague recollection, but felt this was the time to look intelligent.

"Mitch Jackson was my staff sergeant; the best soldier I've ever had." Parnell screwed up his eyes while he thought. "Some man! He was too efficient and brave to last. So, we are going to help his old man, Dirk. We'll take his hundred bucks and, by taking it, he is our client. We are going to give him our best service. Understand?"

"Yes, sir.”

"This assignment is going to be your pigeon." Parnell went on giving me his military stare. "Go and see the old coot and find out what's biting him. Treat him as a VIP. Understand?"

"Yes, sir."

"Get the dope, then come back and report to me. We'll see what we can do when we get the details. You get off tomorrow morning." He studied me. "This will be your chance to show me how you are shaping, so let's have a nice, smooth performance. Right?" He tossed a hundred-dollar bill across the "Use this for expenses." He gave a sly grin. "And not a word about this to Glenda. If she knew I was taking on a hundred-dollar client she would split her pantyhose."

"Yes, sir."

"Okay, Dirk. Let's have some fast action. We don't want to waste a lot of time, but I want this tied up."

With a wave of his hand, he dismissed me.

I returned to the office I shared with Chick. He was going through a fat file which I knew covered all the employees of the self-service store we were watching.

He looked up.

"What's new?"

I sat down and told him.

"Mitch Jackson?" He released a long, low whistle. "Some man! I served with him when he was staff under the colonel. I didn't know he was married. Must have been when we had a month's leave. He never told us." He looked thoughtfully at me. "Did the Colonel tell you how Mitch died?"

"He didn't say."

"It's something that was a military secret. You had better know in case, when talking to his father, you drop a bollock. Just keep this to yourself."

"How did he die then?"

"It was a typical army screw-up. A patrol of twenty men were sent into a big patch of jungle where it was thought the Viets were hiding. We had been losing too many men by sniper fire and we were held up in the advance. The brigade came to this patch of jungle, around a thousand acres: ideal for snipers. The colonel sent in this patrol, led a veteran sergeant. Their job was to test the ground and flush out the snipers. The rest of the brigade waited on a hill, looking down on this patch of jungle. Word had gone back to headquarters that the brigade was held up. So the situation was these twenty men were going into the jungle and the brigade was waiting and watching. Mitch wanted to go with the patrol. He always wanted to be in the forefront of any action, but the colonel wouldn't let him. The patrol was scarcely into the jungle when a signal came from headquarters that bombers were on their way and they had orders to blast the patch of jungle with napalm. Some goddamn Air Force general hadn't seen the colonel's signal that the patrol was going in, and had ordered out his bombers. It was too late to call off the bombers. They could already be heard approaching. Mitch got into a jeep and drove down with the colonel yelling to him to come back, but Mitch was thinking of those twenty kids and nothing could stop him. He drove into the jungle until the jeep smashed into a tree, then he ran in, bawling to retreat. Seventeen youngsters got out as the bombers began to plaster the patch with napalm. We saw Mitch come out with them, then he stopped, found three were missing. He sent the seventeen running up the hill and he went back into the jungle." Chick blew out his cheeks. "By then the jungle was on fire and lumps of burning napalm spreading. It was the maddest and bravest thing I don't ever want to see again."

"What happened?"

"That's how Mitch died: saving the lives of seventeen kids. What we found of him was shovelled into a burlap bag. Just his steel identity bracelet to tell us we had found him."

"And the other three?"

"Nothing: bits of bone, a lump or two of cooked meat, and, what made it worst, there were no Viets in the jungle. They must have pulled out hours before we arrived. It was a cover-up. What we call in the Agency a fig-leaf job. The Air Force general who had ordered the strike was transferred. The colonel raised hell, but the top brass muzzled him. The citation for the Medal of Honor, which the colonel insisted Mitch should have, said it was for saving the lives of seventeen soldiers, and Mitch had been instantly killed by a Viet sniper while getting the men out of the ambush." Chick shrugged. "I made nicer reading for his father than what really happened."

"Well, thanks for telling me. I'll watch it when I talk to his father."

Chick pulled the file towards him.

"Yeah," he said. "I wonder what the father is like. If he's anything like his son, you watch it."

The following morning, equipped with an overnight case and a large-scale map, I set of in one of the office cars for West Creek.

Although I had spent most of my life in Florida, this would be new country to me. The map told me that West Creek was a fey, miles to the north of Lake Placid. The guide-book I had consulted told me West Creek had a population of 56 and it survived by breeding frogs which I learned fetched fancy prices during the winter when the frogs were difficult to catch. There seemed to be a constant demand for frogs' legs by the swank restaurants along the coast.

The drive took a little over three hours and I stopped off at Searle, a thriving fanning town, growing tomatoes, peppers, Irish potatoes and squash, and which was according to my map a few miles from West Creek. I had had only a cup of coffee for breakfast and I was hungry. Besides, it is always smart to chat up the locals before moving onto the scene to be investigated.

I went into a clean-looking cafe-restaurant and sat down at a table by one of the windows, overlooking the busy main street; crammed with trucks, loaded with vegetables.

A girl came over and gave me a sexy smile: a nice-looking chick, blonde, wearing tight jeans and a tighter T-shirt.

"What's yours?" she asked, placing her hands on the table and leaning forward so her breasts did a jig behind the shirt.

"What's the special?" I asked, restraining the urge to poke one of her breasts with a forefinger.

"Chicken hash, and the chicken didn't die of old age."

"Okay. I'll take it."

I watched her swing her neat bottom as she made for the kitchen. Even a backwater like Searle could provide excitement.

I became aware that there was a tall, elderly man with a heavy white moustache, stained yellow with tobacco smoke, up at the bar. He was pushing seventy and he wore a soiled Stetson hat and a dark suit that was nickel-plated with age. He looked at me and I gave him a nod and a smile. He stared for a long moment, then picking up his glass, he came over to me.

"Howdy, stranger," he said and sat down. "Don't often see strange faces in this neck of the woods."

"Just passing through," I told him. "Taking a look. I'm on vacation."

"Is that right?" he sipped his drink. "You could do worse. Plenty of interesting things to see. One time this district was a'gator country. Still a few to be seen of Peace river."

"I saw some at Everglades. Interesting."

The girl brought the chicken hash and slapped the plate down before me. She looked at the elderly "You want something or are you seat-warming?"

"I have something," the elderly man said and lifted his glass. "If I were ten years younger I would have something for you."

"Make it thirty years younger and I might be interested," she said with a sexy grin and swished away.

The elderly man shook his head.

"The young today have no respect for their elders."

I could hate said the young today had no reason to respect their elders, but I stopped short. I wasn't going to get into that kind of discussion.

I began on the chicken hash.

"A'gator country," the elderly man said. "You ever heard of Alligator Plan? No, I guess you're too young. He is folklore around here."

I munched, finding the chicken had died of old age. "Folklore?"

"Yeah. Know what? Plan would hide along the hank until an a'gator surfaced, then he would dive in and grapple with the reptile. He would get astride it and hook his thumbs into its eyes. Never failed, but it needed a lot of strength and guts. He said shooting a'gators was a waste of a bullet."

"Those were the days," I said. "There was only one man who could do what Piatt used to do, but, eventually, he got unlucky. Piatt died in his bed, but old Fred Jackson lost both his legs."

Time and again, when I was on a job and got into conversation with one of the natives, I struck gold, but not this fast.

Casually, I said, "Fred Jackson? Would he be the father of Mitch Jackson, the war hero?"

The elderly man looked sharply at me.

"That's right. How did you know Fred lives up here?"

"I didn't. You told me." I looked directly at him. "I didn't get your name. I'm Dirk Wallace."

"Silas Wood. Glad to know you, Mr. Wallace. What's your line?"

"I'm in the Agency business."

"Agency? What's that mean?"

"I collect information: background material for writers."

He looked impressed.

"Is that right? I'm retired. Use to have a tomato farm, but there's too much competition these days. I sold out."

"Tell me, Mr. Wood, did Fred Jackson lose his legs after or before he lost his son?"

The question seemed to puzzle him. He pulled at his long nose and thought about it.

<

br /> Finally, he said, "Well, since you ask, Fred lost his legs when Mitch was a nipper. Fred must be seventy-eight now if he's a day. Mitch did most everything for Fred until he got drafted. By then, Fred had got used to being legless. He became real handy getting around on his stumps. He is still the best frog-catcher around here and he makes a tidy living."

"You knew Mitch?"

"Knew him?" Wood again pulled at his nose. "Everyone around here knew Mitch. I nor anyone else thought he would turn out to be hero. It just shows you you can't judge kids: like that girl. She could settle down, but she won't ever be a national hero . . . that's for sure."

"Mitch was wild?"

Wood finished his drink and gazed unhappily at the empty glass.

This was a hint, so I took his glass and waved it at the girl, who was resting her breasts on the bar counter and watching us.

She brought a refill and set it before Wood.

"That's your second." she said, "and your last." Looking at me, she went on, "He can't carry more than two, so don't tempt him," and she returned to the bar.

Wood gave me a sly grin.

"Like I said, the young have no respect for their elders."

I was asking . . . “was Mitch wild?”

I had finished the chicken hash, not sorry the meal was over. My jaw felt tired.

"Wild? That's not the right word. He was a real hellion." Wood sipped his drink. "He was always in trouble with the sheriff. No girl was safe within miles of him. He was a thief and a poacher. I'd hate to tell you how many tomatoes he stole from my farm or how many chickens disappeared or how many frogs vanished from other farmers' frog-barrels. The sheriff knew he was doing the stealing, but Mitch was too smart for him. Then there was this fighting. Mitch was real vicious. He would often come into town in the evening and pick a quarrel. Nothing he liked better than to fight. Once, four young guys who thought they were tough ganged up on him, but they all landed in hospital. I had no time for him. Frankly, he scared me. He even scared the sheriff. The town was glad when he got drafted and we saw the last of him."

Wood paused to sip his drink. "But one can forgive and forget when a guy wins the Medal of Honor. Right now the town is proud of him. Let bygones be bygones I say." He winked. "Many a girl cried herself to sleep when the news broke that he was dead. He seemed to be able, by just snapping his fingers, for the girls to spread their legs."

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

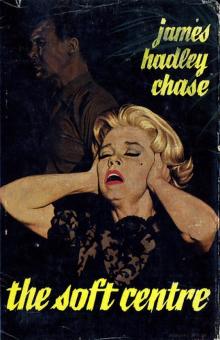

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

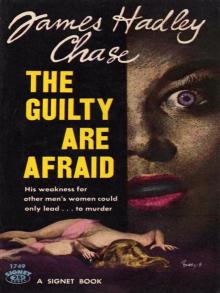

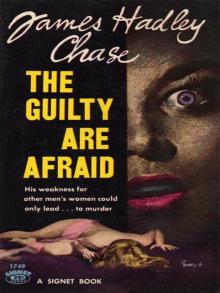

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

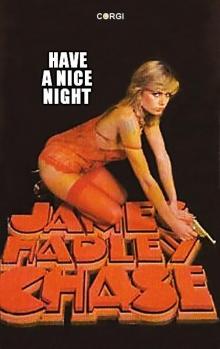

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

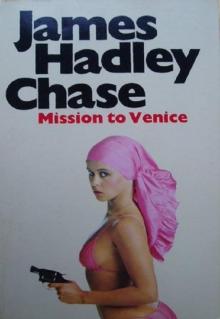

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

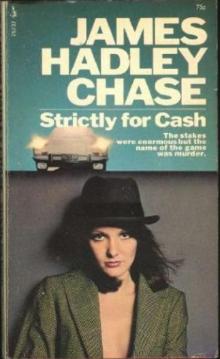

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

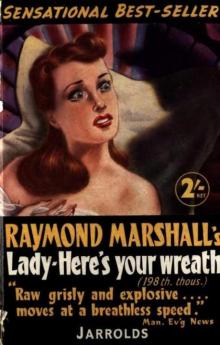

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

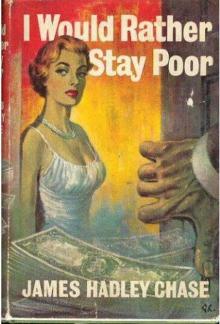

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

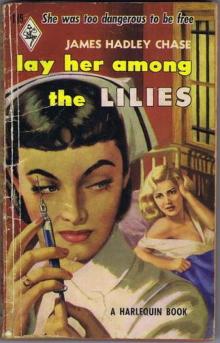

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

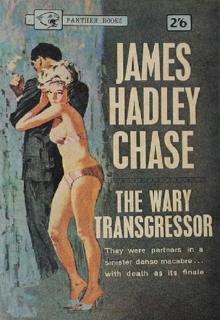

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

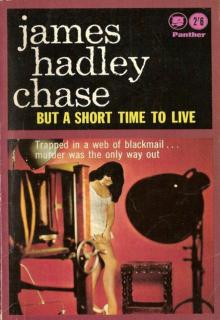

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail