- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf Page 2

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf Read online

Page 2

I was absorbing all this with interest.

"And his father? Was he like his son?"

"Fred? No. He was a worker and he was honest. Mind you, he was tough, but straight. When he lost his legs, he changed. Before that happened, he would come into town and be good company, but not after losing his legs. He no longer welcomed visitors. He still hunted frogs with the help of Mitch, but he stopped coming to town and anyone who went up there got short shrift. Even now. at his age, he still hunts frogs. Once a week, a truck goes up there and takes his catch. I guess he must live on rabbits and fish. I haven't seen him for a good ten years."

"How about Mitch's mother? Is she alive?"

"I wouldn't know. No one around here ever saw her. The story is some woman tourist went up there to take photographs of Fred and the a'gators. That was when he was in his prime. I guess he was like Mitch with women. Anyway, one day, Fred got landed with a baby: left outside his shack. That was Mitch. Mind you, I won't swear to any of this, but that was the story going around Searle. Fred brought him up the hard way, hut he made him attend school. When Fred lost his legs, it was Mitch who saved him. From then on, Mitch looked after his father until Fred could stump around on his thighs. That's the only good thing I can say for Mitch: he sure was fond of Fred: no question about that."

"Interesting," I said.

"That's right. It gave the town a lot to talk about. Not every town our size has a national hero. Then there was the grandson."

I showed mild interest.

"You mean Mitch's son?"

"That's right. It was a mystery. Some nine years ago, a kid arrived here. He was around eight years of age. I remember seeing him arrive. He looked like a little bum: as if he had been on the road for days: dirty, long hair, his shoes falling to bits. He had an old battered suitcase, tied up with string. I felt sorry for him. I like kids. I asked him what he was doing here. He spoke well: He said he was looking for Fred Jackson, who was his grandpa. I couldn't have been more surprised. I told him where Fred lived. The kid looked starved so I offered him a meal, but he was very polite and said he wanted to get to his grandpa quickly. Josh, our mailman, was setting off in his truck and I got him to take the kid. At the time, Mitch was in the Anny. There was a lot of talk in the town as you can imagine. The school-teacher went up to see Fred. For a change, Fred saw and talked to him. The upshot was the kid, Johnny Jackson, attested school: riding down here on a cycle."

"Was Johnny like his father?"

"Not a scrap. He was a nice-looking, quiet, polite kid, may be a bit soft, but he was smart at school. The kids hadn't much time for him. He was a loner and never talked about Mitch. When the kids asked him, he told them he had never seen his father. He had been born after his father had gone overseas. When the news broke that Mitch had been killed and had won the medal, the kid didn't turn up at school. By then, he was fourteen. The school teacher went up there and Fred told him to get the hell out and stagy out. After that, and that was six years ago, no one has seen the kid. My guess is he got tired of living rough and took off. Can't say I blame him. Old Fred really lived rough." Wood finished his drink, sighed, then took out an old silver watch and consulted it. "I must get moving, Mr. Wallace. My wife has a hot meal for me, always dead on one o'clock. She gets kind of peevish if I'm late." He shook my hand. "Have a good vacation. I hope to see you around. We could have another drink together."

When he had gone I signalled to the girl for coffee. By now there were a number of truckers eating: none of them looked my way and I wasn't interested in them. I was only interested in the natives.

The girl brought the coffee.

"Don't believe everything old Wood tells you," she said, sating down the cup. "He's senile. What was he yakking about?"

"Mitch Jackson."

Her face lit up and she got that soppy expression kids get when they are turned on.

"There was a real man!" She closed her eyes and sighed. "Mitch! He's been dead now for six years, but his memory lingers on. I only saw him once: that was when I was a kid, but I'll never forget him."

"Wood said he was a hellion. In my book, if a guy wins the Medal of Honor he has to be great." I fed her this line because I could see by her besotted face Mitch meant more to her than Elvis Presley meant to millions of teenagers.

"You can say that again! Who would have thought his son would be such a drip?"

I stirred my coffee. It seemed my day to pan gold.

"Was he?"

"We were at school together. All the girls were after him because Mitch was his father. What a drip! He just ran like a frightened rabbit."

A trucker bawled for his lunch. The girl grimaced and left me.

I sipped the coffee and thought over what I had learned. According to Silas Wood, Fred's grandson hadn't been seen since Mitch had died. Again according to Wood the town's opinion was the boy, Johnny Jackson, had left. This didn't make sense to me. If the boy had left six years ago, why should Fred Jackson write to Parnell now to start an investigation to find him after this long lapse?

I decided to inquire around some more before setting of for Alligator lane. I paid my check and went out onto the busy street. Pausing to look around, I saw a notice with an arrow pointing:

Morgan & Weatherspoon

Bess Frog saddles

Fred Jackson was in the frog business. I could pick up some information so I followed the direction of the arrow down an alley to double gates on which was another sign:

Morgan & Weatherspoon

You Have Arrived: Enter

The stench coming over the high wooden fence turned my stomach. I pushed opened one of the gates and walked into a big courtyard where two open trucks were parked. Each truck was loaded with barrels and from the barrels came croaking noises.

Across the way was a concrete building. Through the big window. I could see a man in a white coat, working at a desk. I walked up the three steps, pushed open the door and entered a small, air-conditioned office. I hastily closed the door before the stench in the yard could invade.

The man at the desk gave me a friendly smile. He was around forty-six, then, with thinning black hair and sharp features.

"What can I do for you?" he asked, getting to his feet. He offered his hand. "Harry Weatherspoon."

"Dirk Wallace," I said, shaking hands. "Mr. Weatherspoon, I'm here to waste a link of your time, but I hope you will be indulgent."

His smile widened, but his small, shrewd eyes regarded me speculatively.

"Right now, Mr. Wallace, I have time. In half an hour, I'll be busy, but at this moment I am digesting lunch, so take a seat and tell me what's on your mind."

We sat down.

"I work for an agency that collects information for writers and journalists," I said, using the never-failing cover story. "I'm the guy who feeds them with facts. They write up the facts and make millions. I don't." I gave him a rueful smile.

"So, I'm investigating the background of Mitch Jackson, oar national hero, his father and frogs as an important magazine is planning to do a feature on Mitch."

He scratched his thinning pate.

"I would have thought that was stale news. There's been a lot written about Mitch Jackson."

"Well, you know how it is, Mr. Weatherspoon. I'm looking for a new angle."

He shrugged.

"Well, I can tell you about frogs, but I have never met Mitch Jackson. From what I've heard, I'm not sorry. Now, frogs. You notice the smell? Well, you get used to it. Frogs are smelly and live in smelly places. Frog-legs or saddles as we call them in the trade, bring high prices. Personally, I don't like them, but, served in a garlic sauce, there are a lot of wealthy people who do like them. It's quite a flourishing industry. Here, we collect from the frog-fanners, process and sell to restaurants." He leaned back in his chair and I could see by his animated expression frogs were close to his heart. “The trick, of course, is to catch the frogs. Happily, that's not my headache. Now, Fred Jackson has been, for thirty years,

our best supplier, not only in quantity, but now I don't rely on him so much. He's getting old . . . aren't we all?"

He favoured me with another wide smile. "Frog-farmers work this way: they find the right kind of land with swamp and ponds and either rent it or buy. Fred Jackson was smart. He bought his land years ago for next to nothing. Frogs live on insects. Breeders, like Jackson, throw rotten meat around the pond. The meat attracts blowflies. Frogs like blowflies. While they are catching blowflies, the fanners catch them. Jackson is an expert. Not satisfied with a daylight catch, he's installed electric light around his ponds to attract moths and bugs. So the frogs also eat at night and Jackson is there to catch them. A female frog lays anything from ten to thirty thousand eggs a year. Ninety days later, tadpoles arrive. It takes two years before a frog is fit to eat." He smiled again. "Lecture over."

"Thank you," I said. "That's just what I want." I paused, then went on, "You tell me that you never met Mitch Jackson, and yet you said, in spite of him being a national hero, you're not sorry. Would you explain that?" He looked a little shifty, then shrugged.

"You should understand, Mr. Wallace, I am not a native of this town. It has taken me some time to get accepted. I bought a partnership with Morgan who retired and has lately died. I run this business. Mitch Jackson has a big reputation here because he won the medal, so I wouldn't want to be quoted. The kids here adore his memory, so what I'll tell you is strictly off the record."

"No problem," I said. "You don't get mentioned if that's what you want."

"That's what I want." He stared hard at me, then continued, "I came to Searle after Mitch Jackson had died. I heard plenty about him. The natives had been scared of him. According to them he had been a vicious thug, hut, when he won the medal, the town made him folklore and the girls here shot their stupid lids and now treat his memory as if he was some god-awful pop-singer."

I let that one drift. When I was a kid, my idol was Sinatra . . . Kids have to have idols.

"If you want the inside dope about Mitch Jackson, you should ask Abe Levi," Weatherspoon went on. "He's one of my truckers who collects frog-barrels up north. He's been collecting from Fred Jackson for years." He looked at his watch. "He'll be in the processing-shed right now. Do you want to talk to him?"

"Sure, and thanks, Mr. Weatherspoon. Just one other thing: anything you can tell me about Fred Jackson?"

He shook his head.

"No. I've never seen him. I heard he lost both legs, fighting an alligator. While he was recovering, Mitch did the frog-catching, then Fred got mobile again. His catch has been falling off recently, but that's to be expected at his age. From what I hear, he's tough and honest."

I got to my feet.

"I'll talk to Levi."

He pointed through the window.

"That big shed there. He'll be taking his lunch." He stood up. "Nice meeting you, Mr. Wallace. If there's anything else you want to know about frogs, you know where to find me."

We shook hands and I walked out into the stench.

In the shed, where a number of coloured girls were dissecting frogs, a sight and smell that made me want to gag, I found a man, around sixty-five, eating out of a can of beans. That anyone could eat in that awful stink beat me, but this man, short, squat, powerfully built with a greying beard and none too clean, seemed to be enjoying his meal.

I gave him the same story as I had given Weatherspoon about collecting information for an agency. He listened while he ate, then regarded me with grey eyes that lit up with cunning light of the poor.

For years I had been digging for information and I knew that look.

"Mr. Weatherspoon tells me," I said, "you could give me information. I don't expect information for nothing. Would five bucks interest you?"

"Ten bucks would be better," he said promptly.

I took a five-dollar bill from my wallet and waved it in his direction.

"Five to start. Let's see how we go."

He snapped the bill from my fingers the way a lizard snaps up a fly.

"Okay, mister. What do you want to know?"

"Tell me about Fred Jackson. You've known him for years, I'm told."

"That's right, and the more I see him the less I want to. He's a mean old cuss. Okay, I guess most people would turn mean if they lost their legs, but Fred has always been mean."

"Mean? Are you saying he is close with money?"

"I didn't say that, although he is close, but he has a mean nature. The kind of man who would do dirt to his best friend and think nothing of it." Levi squinted at me. "Not that Fred ever had any friends. He has a mean character, like his son."

"His son won the Medal of Honor."

Levi snorted.

"He won it because he's tough, mean and vicious. He never cared a damn what he walked into. I don't call that brave. I call it stupid. The Jacksons are rotten. I've no time for either of them. I've been up to Jacksons' cabin every week for more than twenty years. Never once did either of them offer me a beer. Never once did either of them give me a hand loading the barrels, and frog-barrels are mighty heavy. Mind you, now Fred's lost his legs, I don't expect help, but Mitch, when he was around, watched me strain my guts out and just grinned." He snorted. "Other frog-fanners always give me a beer and a hand, but never the Jacksons." He looked inside the tin of beans, scraped, found a couple of beans and ate them.

"All this talk about Mitch Jackson being a national hero makes me want to puke. The fact is the towns well rid of him."

I wasn't getting anything more from him than I had already got from Weatherspoon.

"Did you meet the grandson?"

"Just once. I saw him up there. I arrived in the truck and he was washing clothes in a tub. I guess Fred made him earn his keep. As soon as he saw me, he went into the shack and Fred came out. I never spoke to the kid. I guess he got-choked living with Fred and took off when Mitch was killed. I only saw him this once. That's close on six years ago."

"He would be around fourteen years of age?"

"I guess. A skinny kid, nothing like either of the Jacksons. I've often wondered if he was really Mitch's son. Mitch had the kind of face you see in police mug-shots. This kid had class. The kids at his school said that. They said he was different. I guess he sure must have took after his mother."

"Know anything about her?"

Levi shook his head.

"No one does. Probably some piece Mitch screwed. Could have been any girl around the district. He never left the girls alone. I dunno, maybe the kid had the same itch. I remember seeing a girl up there."

He thought, then shook his head. "That was only four months ago, long after the kid was thought to have taken off."

Not showing my interest, I said casually, "Tell me about the girl."

"I only caught a glimpse of her. She was washing clothes the way the kid washed clothes in a tub outside the cabin. As soon as I drove around the bend, she ran into the cabin and kept out of sight. When Fred turned up, I asked him if he had hired help, but he just growled at me: no more than I could expect from him. I thought he must have hired a girl from the town to replace the kid. I admit I was nosey and I asked around, but no one knew of any girl working for Fred." He shrugged. "I never saw her again."

"What was she like? How old?"

He licked the spoon he was holding, then put it in his pocket.

"Young, thin with long yellow hair. I noticed her hair. It reached to her waist and was dirty."

"What was she wearing?"

"Jeans and something. I don't remember. Maybe Johnny was there after all and she was shacking up with him. Fred wouldn't have cared. He didn't care about the way Mitch went on with girls." He paused, then with a sly grin, asked, "How am I doing?"

"One more question. I'm told Mitch was a loner. Didn't he even have one friend?"

Levi scratched his dirty beard.

"Yeah, there was a jerk Mitch went around with. Like Mitch: no good." He gazed into space. "Right now, I don't seem to remember his name."

I produced another five-dollar bill, but kept it out of his reach. He even the bill, scratched his beard some more, then nodded.

"Yeah. I remember now . . . Syd Watkins. He got drafted the same time as Mitch. The town was glad to see both of them go. His ma and dad were respectable. They ran the grocery store at Searle, but when she died he retired. He couldn't run the store without her and Syd never did a day's work in his life."

"Mitch and Syd were pals?"

Levi grimaced.

"I wouldn't know about that. They were thieving partners and went around together. When Mitch picked a quarrel, Syd never joined in. He just watched. You could say he was the brains and Mitch was the brawn."

"After the war, did he come home?"

"No. From time to time, I have a drink with his dad. The old man is always expecting to hear from his son, but, so far, never has. All he knows is Syd was discharged from the army, came back to the States and then dropped out of sight. It's my bet he's up to no good."

I brooded for a long moment, then gave him the other five-dollar bill.

"If I think of anything, I'll see you again," I said. I was longing to get out of that shed and breathe some clean smelling air. "Are you always here at this time?"

"Sure am," he said and put the bill in his pocket. "How do I get to Fred's place?"

"You got a car?"

I nodded.

"It's some five miles from here." He gave me detailed directions. "You be careful with Fred . . . he's mean."

With a lot to think about, I walked to where I had my car and set off for Alligator Lane.

As I drove up the main street, I passed the sheriff s office. I wondered if I should stop off and introduce myself. From past experience, I had learned local sheriffs could be hostile to an operator, nosing around their territory, but I decided I should first talk to Fred Jackson. He had hired the agency to find his grandson. Maybe he wanted to keep the investigation confidential.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

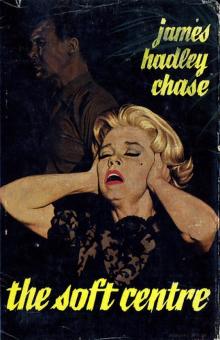

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

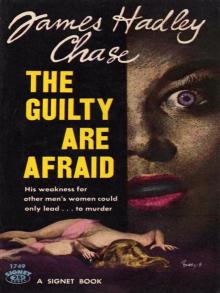

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

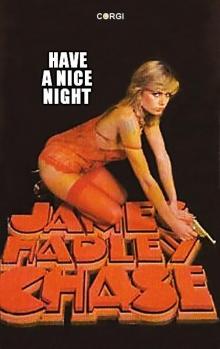

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

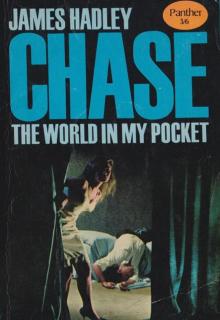

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

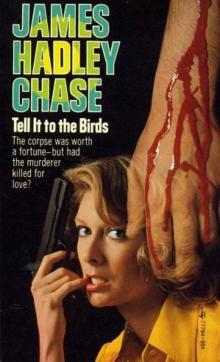

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

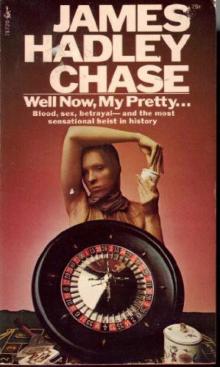

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

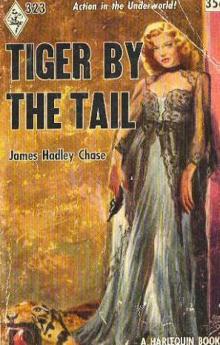

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail