- Home

- James Hadley Chase

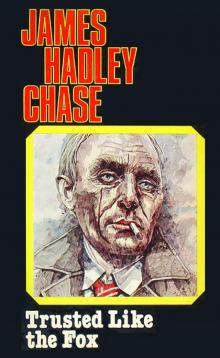

Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox Read online

James Hadley Chase

Trusted Like The Fox

1948

Synopsis

Two killers wanted her — one for protection and one for prey. One of them had slain a helpless man to hide the secret of his identity. And he was quite prepared to kill the girl if she tried to double-cross him. But he’d reckoned without that terrible accident — and he was totally unprepared for the insane murderer who made death a ritual with a silver-handled knife.

Table of Contents

Synopsis

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eightteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

PROLOGUE

He had everything ready: the soiled bandages, the knife, the dirty, tattered battledress, the damp mud to rub on his hands and feet. Most important of all, he had the identity papers of the dead David Ellis whose body was rotting out there in the sun.

But in spite of the perfection of the plan, Cushman was nervous. There were tiny sweat beads on his forehead, his heart thudded unevenly against his ribs and he had a disgusting taste of bile in his mouth.

He stood in the tiny, evil-smelling office and listened. If all went well, the identity of Edwin Cushman, the notorious renegade, would have ceased in a few minutes to exist, but before that happened Hirsch would have to be silenced. No easy task this, for Hirsch was as strong as a bull. There must be no bungling. A lightning stroke from behind was the only possible method of killing such a man.

Cushman glanced at the clock above the door. A second or so more and Hirsch would be here.

He waited, listening. His mouth was dry, his nerves jumpy. He felt that the threat of violent death could not be worse than these halting seconds.

The sound of boots crashing on the wooden boards of the passage outside made him stiffen. Then the office door jerked open and Hirsch came in. He was an enormous man, fat, powerful, built like a Japanese wrestler. His S.S. uniform clung to his great frame, hampering his muscles, and the seams of his jacket creaked with every movement he made.

“They’ll be here in twenty minutes,” he burst out, seeing Cushman. His close-cropped head shone with sweat. “Then — kaput!” He pushed past Cushman, went to the window and peered out at the ghastly wilderness of death that was Belsen.

Cushman fingered the knife which he held behind his back, edged towards the vast bulk before him. There was a sickening stench of stale sweat and filthy feet coming from Hirsch. As he jerked round, Cushman eyed him stolidly, kept his hand behind him.

“Well, Englishman, how do you like it now?” Hirsch sneered. “Too late to scuttle back to Berlin, eh? You thought you’d done well for yourself, didn’t you? I’ll see you don’t escape. I’ll tell them who you are. I hate traitors. They’ll string you up far higher than me.” His hard little eyes, red-flecked with terror, went to the window again, then back to Cushman. “You’ll be lucky if your countrymen out there don’t get you first. No one loves a traitor, Cushman. I wouldn’t be in your place . . .”

Cushman smiled thinly. He felt he could afford to smile. “Don’t call me a traitor,” he said. There was a harsh jarring note in his voice that set a seal of identity upon it. You had only to hear it once and you would never forget it. It was a voice known to millions of British men and women who had listened to it during the five years of total war. It was an unusual voice, not very deep, very distinct, sneering, harsh. “At heart I am a better German than you,” he went on. He had often rehearsed these words for such a moment as this. “It was my misfortune to be born British. I did what my conscience dictated, and if I had my time over again I would still do the same.”

Hirsch made an impatient movement. “Keep that stuff for your judges,” he said. “You have less than twenty minutes of freedom. Why don’t you go out there and show yourself? They’re waiting for you. They know the British are coming. Go out there. Let’s see the colour of your guts. Your whip won’t frighten them now.”

“Don’t be so melodramatic,” Cushman said, moving closer. He stared up at the vast bulk before him. It was like David looking at Goliath. “Go out there yourself if you feel so brave.”

Hirsch shivered, looked out of the window again.

It was Cushman’s opportunity.

Fear and hate drove the stab.

They drove with such overwhelming power that Hirsch’s gross body crashed like a felled tree. Cushman had picked a spot between the vast shoulder blades and the force of the stroke sent a jar up his arm. As Hirsch went down he upset a chair beside the desk. This clatter startled Cushman. He stepped back, jerking the broad blade of the knife from the slab of fat and muscle in which it had been buried. He stared at the dark blood that welled from the cut in Hirsch’s shirt.

The gross mountain of flesh heaved itself up. Cushman selected his spot, struck again. The knife sank into the lung cavity. Hirsch made a feeble movement, caught hold of Cush- man’s wrist, but there was no strength in the thick fingers.

Cushman, cold and deliberate, pulled away, then struck again. Hirsch’s lungs began to pump spurts of blood through his wounds. In his last writhing effort to get at Cushman, his legs beat frantically up and down: great tree trunks of legs that crashed noisily on the floor. Then suddenly the legs stopped thrashing. Hirsch glared up at Cushman, who spat in his face and, standing over him, sneering and triumphant, watched him die.

The sound of distant gunfire warned Cushman that there was no time to waste. He hurried to the door, turned the key. Then, without giving Hirsch another glance, he threw off his S.S. uniform and stood naked before the mirror on the wall. He did not look at himself in the mirror. He was only too bitterly aware of his frail physique, the lack of muscles, the narrow chest and the coarse blond hair that covered his limbs. This was no body for a man of his courage, vision and ambition. But although his body might be puny there was nothing the matter with his brain. He had every confidence in his mental alertness, his ingenuity, his clear-sightedness and shrewdness. It was ridiculous for a man of his abilities and mental equipment to have such a feeble body: as ridiculous as setting a priceless gem in a hoop of brass. But he had been over this argument so often before that he was sick of it. He had to make do with what nature had given him.

He spent a feverish five minutes smearing his feet, hands and body with mud; then he put on the tattered khaki battledress, not without a shudder. He had stripped it from a rotting corpse, and the horrible task of removing the fat white maggots from the seams of the garment still lived vividly in his memory.

As he moved to a cupboard on the far side of the room, his naked foot trod in the blood that dribbled out of Hirsch’s wounds. It was warm and sticky. He started back, a tiny sound of horror escaping through his dry lips before he could control himself. Shuddering, he wiped the sole of his foot on Hirsch’s sleeve, then opened the cupboard and took from it the soiled bandages and the identity papers. He glanced at the papers.

They were as familiar to him as his own right hand. There was not one word written on those papers that he hadn’t engraved on his mind.

Cushman had foreseen the end of Germany long before the other British renegades had even thought of the possibilities of defeat. The siege of Stalingrad had been to him the writing on the wall. There was time, of course, but the end was certain. Quietly and methodically he had begun his preparations for his future safety. He kept his own counsel, continued to work at the German Ministry of Propaganda, broadcasting his stupid poison to the British people who listened because they thought what he had to say was funny. He allowed the other Englishmen in Berlin to think he was undisturbed by the news that kept coming in of continuous German defeats, but all the time he watched and waited for the opportunity to put his plan into action.

It was only after the successful landing in Normandy by British, Canadian and American troops had begun that Cushman decided that the time was ripe. It was then that he suggested to his superiors that he should be allowed to undertake more active duties now that the final test of strength had come. Able-bodied men were at a premium; his reputation as a loyal servant was above reproach, and he was Congratulated. In a few days he received a commission in the S.S. guards and was sent to the Concentration Camp at Belsen as Sub-Commandant. This was no chance appointment. Cushman had been pulling strings behind the scenes. Belsen was the first milestone of his road to safety.

The next move was to find a British soldier whose identity Cushman could assume. This took time and great patience, but eventually he selected David Ellis, a man with no relations, no ties and apparently no friends. More important still, Ellis was the only survivor of his battalion that had been carved to pieces at Dunkirk.

It was a simple matter for Cushman to extract all the information he required from Ellis. Cushman was a master of torture, and Ellis, crazed with pain, talked freely. It was a simple matter, too, to alter the records: to give Ellis the identity of one of the many of Belsen’s dead, and to hide Ellis’s papers until the time came for Cushman to use them for himself. And, finally, it was also a simple matter to cut Ellis’s throat as he lay raving in the dark.

The time had come. The British Army was only a mile or so from the gates of Belsen. Hirsch was dead. No one else in the camp knew Cushman was an Englishman. Cushman had already assumed half his disguise. He regarded himself in the mirror. The sallow-complexioned, blunt-featured face he saw reflected in the mirror irritated him. But for the eyes, it was the face of any Tom, Dick or Harry of the lower classes. But the eyes were good. They were the only true indication of his worth, he decided: steel-grey eyes, hard, alert, dangerous.

With a pang of regret, he cut off the small black moustache he had grown long ago when he had been a member of the British Union of Fascists.

The sound of gunfire was now ominously close. He took up the knife, wiped the blade, stared at himself in the mirror. He prided himself on his nerve and his cold ruthlessness; he did not hesitate. He opened the anatomical chart he had ready for the final step in his disguise. With his fountain pen he drew a line on his flesh from his right eye to his chin, following the diagram of the chart and carefully avoiding the facial artery. Then he picked up the knife once more and gritting his teeth, he dug the point of it into his flesh. He knew he must have a legitimate excuse for hiding his face under a mass of bandages. This was the only way, and he did not flinch.

The knife was unexpectedly sharp. Before he realised what he was doing, he had laid his cheek open to the bone. He could see the bone gleaming white, and his yellow molars, heavy with amalgam, through the scarlet lips of the wound. He dropped the knife and staggered forward. Blood gushed down his neck, the whole of his face became a mask of pain. He clung on to the desk; a black faintness crept over him like death.

Overhead a shell exploded and a small portion of the ceiling thudded on to the floor.

The noise brought Cushman back to his senses. Savagely he willed himself back to consciousness. He dragged himself upright, fumbled for the needle and thread. As if in a nightmare he stitched the lips of the wound together. It was only his willpower and the knowledge of his supreme danger that carried him through the operation. With trembling hands he swathed his face and head in the filthy bandages. He had practised bandaging himself until he could put the bandages on automatically without ever looking in a mirror.

The pain in his face, the loss of blood, and the sound of gunfire shook his nerves, but he made no mistakes.

He poured petrol over Hirsch’s great body half-hidden under the desk, put his own uniform and boots nearby. He splashed petrol over the walls and fittings. Then he straightened up, looked once more into the compound. No one would recognise this filthy object now. His face had disappeared under the blood-soaked bandages. His moustache had gone. His S.S. uniform had been replaced by the khaki battledress.

David Ellis was ready to welcome the liberators of Belsen. Edwin Cushman, renegade, was about to disappear for ever in a blazing pyre.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Mr Justice Tucker began his summing-up on the third day of the trial. During the course of his direction to the jury he said: “Now, what did this man, Inspector Hunt, say? He was a Detective-Inspector and he said that he had known the prisoner since 1934; he had not spoken to him but he had listened to him making political speeches from time to time, and he said he knew his voice. He said that on the 3rd September, 1939, he was stationed at Folkestone and he was there till the 10th December, 1939. He said. ‘I then returned to London. While at Folkestone I listened to a broadcast. I recognised the voice immediately as the prisoner’s . . .’ ”

The few members of the public who had succeeded in getting into the packed court had spent the night on the stone steps of the Old Bailey. They had come to feast their eyes on the prisoner who had, for so long, sneered at and taunted them over the German radio in what he had imagined to be perfect safety. Well, they had him now, and no legal arguments, nor the endless quotations from the hundreds of law books overflowing on the solicitor’s table, would save him.

The evidence given on the first day of the trial had revealed how easily he had walked into a trap:

“On the 28th May of this year in the evening, you were in company with a Lieutenant Perry in a wood in Germany, somewhere near the Danish frontier at Flensberg?”

“I was.”

“Were you both engaged in gathering wood to make a fire?”

“We were.”

“Whilst you were engaged in doing that did you see anybody?”

“We came across a person who appeared to be walking in the woods.”

“Who was it?”

“It was the prisoner!

“Did he do or say anything to you?”

“He indicated some fallen wood to us and said to us, ‘Here are a few mores pieces.’ ”

“In what language did he speak first?”

“He spoke to us in French, and then afterwards in English.”

“Did you recognise the voice?”

“I did.”

“As what?”

“As that of the announcer or speaker on the German radio.”

And now in his summing-up the Judge again referred to the prisoner’s voice.

A fat woman in a dusty black coat and a shapeless hat adorned with decaying feathers, sitting on the public bench, leaned forward, grunted.

“As if anyone wouldn’t recognise ‘is voice,” she whispered to a man in a shabby brown suit who was wedged against the wail next to her. “I’d know that voice anywhere. The times I’ve ‘eard it. “Orl right,” I said to myself, time and again, “talk as much as yer like. It don’t make no difference. It don’t upset me — you and yer silly lies," I said. “But you’ll larf the other side of yer face when we catch yer," and that’s wot ‘e’s doing now — larfing the other side of ‘is face.”

The man to whom she was speaking shrank from her. He was a screwed up, bitter figure, below middle heigh

t, fair, with a yellow-white complexion. There was a livid scar running from his right eye to his chin that interested the woman.

“Been in the wars yerself, ‘aven’t yer, matey?” she whispered. “Cor luv me, yer poor face is a proper sight.”

The man with the scar (who called himself David Ellis) nodded, kept his eyes on the Judge who was talking now about British and American nationalities. How they had wrangled about that! There would be no question about his nationality if they ever caught him, he thought bitterly. There’d be no backdoor for him if they ever tricked him into that dock.

“I recognised the voice immediately as the prisoner’s.”

Well, he had thought of that. He wouldn’t be caught as easily as the prisoner. He knew they would recognise his voice again if they ever heard it and he had taken precautions.

This Inspector chap had recognised the prisoner’s voices. The Captain of the Reconnaissance Regiment had also recognised it — recognised it the moment he had heard it. What a mug the prisoner had been to have spoken to the two officers. What had he been thinking about? Asking for it, that’s what it was, asking for it.

Well, he hadn’t been such a fool. Of course the bandages had helped, but then that was part of his plan. When they had finally taken them off he had kept his mouth shut, said nothing. They had been kind to him. Suffering from shock was what they called it. Then when he came up for questioning, when he had to speak, he was prepared. It was amazing what a small pebble under the tongue could do to alter a voice. The thick, stumbling speech was all part of the symptoms, they said, and they hadn’t suspected him for a moment. But he couldn’t carry a pebble about in his mouth for the rest of his days. That worried him. The memory of the British public was long. One false move and he’d be where the prisoner was now. It was so easy to forget that people knew your voice. You spoke suddenly, without thinking. You asked for a packet of cigarettes, for a newspaper, ordered a meal, and the next second you found people looking at you, a puzzled expression in their eyes, and you realised that you’d forgotten to put the pebble in your mouth.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

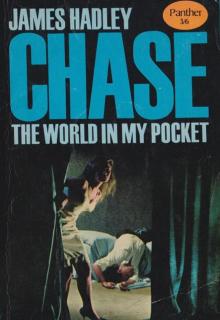

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

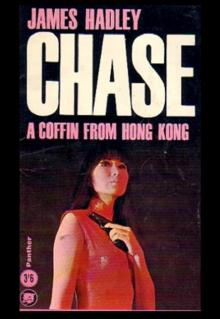

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

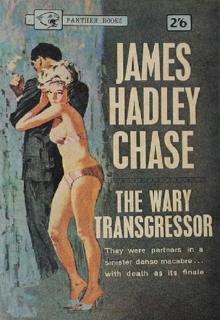

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

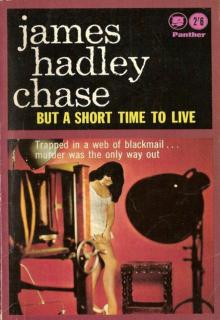

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

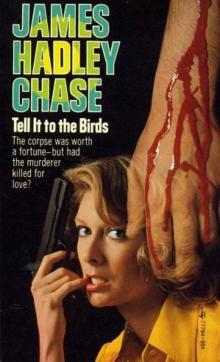

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

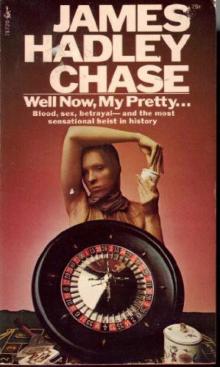

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

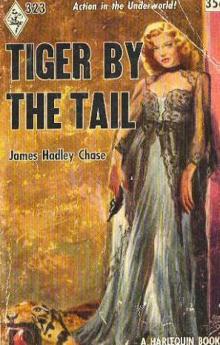

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail