- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene Read online

Table of Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

Have a Change of Scene

James Hadley Chase

1973

ONE

It didn’t begin to show until a month after the crash. You could call it delayed shock although Dr. Melish didn’t call it that, but he is stuck with his technical jargon which is so much blah to you and me: a delayed shock is what he meant.

A month before the crash I was floating in the rarefied air of success. Take my job for instance. I had slaved for it and I finally got it: first salesman with the most exclusive jewellers in Paradise City: Luce & Fremlin. They are in the same bracket as Carriers and Van Cleff & Arpels. In this city every store, shop, gallery and jewellers strive to be the best because this city is a millionaire’s playground, where the snobs, the bulging-with-money boys, the film stars and the showoffs make it a backdrop for their display of wealth.

Luce & Fremlin are the best in their line and being their diamond expert gave me a salary of $60,000 a year which even in this city with its cost of living the highest on the Florida coast, was good money.

I owned a Mercedes convertible, a two-bedroom apartment overlooking the sea, a healthy bank balance and some $80,000 worth of Stocks and Bonds.

I had a wardrobe of good clothes. I was tall, said to be handsome and the best golfer and squash-racket player at the Country Club. Now maybe you will see what I mean when I say I was a man on a cloud of success. . . but wait: to cap all this I had Judy.

I mention Judy last because she was (note the past tense) my most important possession.

Judy was brunette, pretty, intelligent and kind. We met at the Country Club and I found she played a good game of golf. If I gave her six strokes, she would beat me and as I play down to -1 that meant she played a good game of golf. She had come from New York to Paradise City to research for material for old Judge Sawyer’s autobiography. She quickly settled down in Paradise City, became popular and within a few weeks was an integral part of the young community at the club. It took me four weeks and about thirty rounds of golf to discover that Judy was my girl. She told me later it took her considerably less time to discover I was her man. We got engaged.

When my boss, Sydney Fremlin, who was one of those big hearted, slightly overwhelming homosexuals who - if he likes you - can’t do enough for you, heard about the engagement, he insisted on throwing a party. Sydney loved parties. He said he would take care of the financial end and the party must be at the club and everyone - but everyone - invited. I didn’t really want it, but it seemed to tickle Judy, so I went along.

Sydney knew I was about the best diamond man in the business, that without me the high standard of his shop would fall - rather like the standard of a Michelin French restaurant falls when the chef walks out - that all his clients liked me, consulted me and took my advice, so that made me very popular with Sydney, and when one is popular with Sydney he can’t do enough.

That was a month ago. I look back on the evening of the party like a man, driven crazy with toothache, grinds down on the aching tooth.

Judy came to my apartment around 19.00. The party wasn’t due to begin until 21.00, but we had arranged to meet early because we wanted to discuss what kind of house we were going to live in when we married. We had three choices: a ranch type house with a big garden, a penthouse and a wooden chalet out of the city. I dug for the penthouse, but Judy leaned towards the ranch house because of the garden. We spent an hour or so discussing pros and cons, but finally, Judy convinced me a garden was essential.

‘When the kids come, Larry. . . we’ll need a garden.’

There and then I had called Ernie Trowlie, the real estate man we were dealing with and told him I’d be in tomorrow to pay the deposit on the ranch house.

We left my apartment feeling on top of the world and headed for the Country Club. A mile out of the city, and as we drove along the freeway my world came unstuck at the seams. A car shot out of a side turning and rammed us the way a destroyer rams a submarine. For one brief moment I saw the car, an old beat-up Caddy, with a terrified looking kid at the wheel, but there was nothing I could do about it. The Caddy hit the Merc on the offside and threw it across the freeway. My one thought as I blacked out was Judy.

I was still thinking about her when I came to the surface in a private room in the swank Jefferson Clinic paid for by Sydney Fremlin, who was sitting by my bedside crying into a silk handkerchief.

While we are on the subject of Sydney Fremlin let me give you a photo of him. He was tall, willowy with long blond hair and his age could be anything from thirty to fifty. Everyone liked Sydney: he had a warmth and a gush that overwhelm. He was artistically brilliant and had a special flair for designing way-out jewellery. His partner, Tom Luce, looked after the financial end of the business. Luce didn’t know a diamond from a rock crystal, but he did know how to make a dollar breed. He and Sydney were considered rich, and being considered rich in Paradise City put them in the heavy cash bracket. Whereas Luce, fifty, portly and with a face a bulldog would envy, remained behind the scenes, Sydney fluttered around the showroom when he wasn’t designing in his office. I left most of the old hens to him. They loved him, but the rich young things, the wealthy businessmen who were hunting for a special present and those who had been left granny’s gems and wanted them reset or valued came to me.

Homosexuals are odd animals, but I get along with them. I have found that very often they have far more talents, more kindness, more loyalty than the average he-man I rub shoulders with in this opulent city. Of course there is the other side of the coin which can be hateful: their jealousies, their explosive tempers, their spitefulness and their bitchiness that is always much more bitchy than any woman can hope to be. Sydney had all the assets and faults of the average homo. I liked him: we got along fine together.

With his makeup smeared with tears, his eyes pools of despair, his voice trembling, Sydney broke the news to me. Judy had died on the operating table.

I had been lucky, he told me: concussion and a nasty cut on my forehead, but in a few days, I would be as right as rain.

That was what he said: ‘As right as rain.’

He talked like that. He had been to an English public school until they had booted him out for trying to seduce the sports master.

I let him sob over me, but I didn’t sob over myself. Because I had fallen in love with Judy and had planned to live with her for ever and ever I had built inside myself an egg of happiness. I knew this egg had to be fragile: any real hopes of continuous happiness in this world we live in makes for a speculative egg, but I had thought and hoped that the egg would last for some time. When he told me that Judy was dead, I felt the egg go crunch and my technicoloured world turned to black and white.

In three days I was up on my feet, but I wasn’t ‘as right as rain’. The funeral was pretty bad. All the Country Club members turned up. Judy’s mother and father came down from New York. I don’t remember much about them except they seemed to me to be nice people. Judy’s mother looked a lot like her daughter, and that upset me. I was glad to return to my apartment. Sydney stuck with me and I wished to God he would go away, but he sat around and maybe, looking back, he was helpful. Finally around 22.00, he got to his elegant feet and said he would go home.

‘Take a month off, Larry,’ he said. ‘Go golfing. Take a trip. Build up the pieces. You can’t ever replace her, but you have your life to lead. . . so take a trip and come back to us and work like hell.’

�

��I’ll be back tomorrow and I’ll work like hell,’ I said. ‘Thanks for everything.’

‘I won’t have you back tomorrow!’ He even stamped his foot. ‘I want you back in a month’s time, that’s an order!’

‘Balls! Work is what I want, and work is what I’m going to have! See you tomorrow.’

To me this made sense. How could I go on a golfing trip with Judy on my mind? I wouldn’t give a goddamn if I went around in 110. During my brief stay in the clinic I had got it all worked out.

The egg was broken. Like Humpty Dumpty an egg is never put together again. The sooner I got back to selling diamonds the better it would be for me. I was being terribly sensible. This kind of thing happens all the time, I told myself. People who are loved, died. People who make plans, build castles in the air, even tell real estate agents they are going ahead with the purchase of a ranch house find things go wrong and their plans are blown sky high. It happens every day, I told myself. So who was I to pity myself? I had found my girl, we had made plans, now she was dead. I was thirty-eight years of age. Given reasonable luck, I had another thirty-eight years of life ahead of me. I told myself I had to pick up the pieces, get on with my job and, maybe later, find someone like Judy to marry.

At the back of my mind I knew that this was only stupid thinking. No one could ever replace Judy. She had been my chosen, and from now on any other girl would be judged by Judy’s standards, and that, I knew, would give them an impossible handicap.

Anyway, I returned to the showroom with a strip of plaster to conceal the cut on my forehead. I tried to behave as if nothing had happened. Everyone tried to behave as if nothing had happened. My friends - and I had many - gave an extra squeeze when they shook hands. They were all devastatingly tactful, desperately trying to make it appear that Judy had never existed. My clients were the worst to deal with.

They spoke to me in hushed voices, not looking at me, and they fell over themselves to take what I offered instead of haggling happily as they used to do.

Sydney fluttered around me. He seemed determined to keep my mind occupied. He kept buzzing out of his office with designs, asking my opinion - something he had never done before - seemingly to hang on my words, then buzzing back out of sight, only to buzz out again in an hour or so.

The second-in-command in the showroom was Terry Melville, who had served an apprenticeship with Cartier’s of London and had an impressive all-round knowledge of the jewellery trade. He was five years younger than I; a small, lean homo with long silver-dyed hair, dark blue eyes, pinched nostrils and a mouth like a knife cut. Sometime in the past, Sydney had fallen for him and had brought him to Paradise City, but now Sydney was bored with him. Terry hated me as I hated him. He hated my expertise in diamonds, and I hated him for his jealousy, his petty attempts to steal my exclusive clients and his vicious spite. He hated the fact that I wasn’t a queer and, in spite of this, Sydney did so much for me. He and Sydney were always quarrelling. If it wasn’t for Terry’s know-how, and also, maybe, he had something on Sydney, I am sure Sydney would have got rid of him.

When I arrived a few minutes after Sam Goble, the night guard, had opened the shop Terry, who was already at his desk, came over to me.

‘Sorry about it all, Larry,’ he said. ‘It could have been worse - you could have been dead too.’

There was that spiteful, gloating expression in his eyes that made me yearn to hit him. I could tell he was glad this had happened to me.

I nodded and, moving by him, I went to my desk. Jane Barlow, my secretary, plump, distinguished looking and pushing forty-five, came over to give me my mail. We looked at each other. The sadness in her eyes and her attempt at a smile gave me a pang. I touched her hand.

‘It happens, Jane,’ I said. ‘Don’t say anything, there’s nothing to say - thanks for the flowers.’

With Sydney buzzing around me, the clients’ hushed voices and Terry watching me malevolently from his desk, it was a hard day to take, but I took it.

Sydney wanted me to have dinner with him, but I refused. I had to face the loneliness sooner or later, and the sooner the better. For the past two months, Judy and I always had dinner together either at my apartment or at hers; now that had come to a grinding halt. I wondered if I should go to the Country Club, but decided I couldn’t face any more silent sympathy, so I bought a sandwich and sat alone in my apartment, thinking of Judy. Not a bright idea, but this first day had been hard to take. I told myself that in another three or four days my life would become adjusted, but it didn’t.

More than my egg of happiness had broken in the crash. I’m not trying to make excuses. I’m telling you what the head-shrinker finally told me. I had confidence in myself that I could ride this thing out, but there was mind damage as well as the broken egg. We didn’t find this out until later, and the head-shrinker explained this mind damage did account for the way I began to behave.

There is no point in going into details. The fact was that over the next three weeks I deteriorated both mentally and physically. I began to lose interest in the things that had, up to now, been my life: my work, golf, squash, my clothes, meeting people and even money.

The most serious of them all, of course, was my work. I began to make mistakes: little slips at first, then bigger slips as the days went by. I found I didn’t care if Jones wanted a platinum cigarette case with ruby initials for his new mistress. I got him the case, but forgot the initials. I forgot too that Mrs. Van Sligh had particularly requested a gold, calendar watch for her little monster of a nephew, and I sent him the gold watch without the calendar. She came into the shop like a galleon in full sail and slanged Sydney until he nearly burst into tears. This will give you just an idea the way I slipped. In three weeks I made a lot of similar mistakes: call it lack of concentration, call it what you will, but Sydney took the beating and Terry gloated.

Another thing: Judy always supervised my laundry. Now I forgot to change my shirt every day - who cares? I used to have a haircut once a week. For the first time since I can remember I now had fuzz on the nape of my neck - who cares? And so on and so on.

I quit playing golf. Who the hell, except a lunatic, I asked myself, wants to hit a little white ball into the blue and then walk after it? Squash? That was a distant memory.

Three weeks after Judy’s death Sydney came out of his office to where I was sitting staring dully down at my desk and asked me if I could spare him a minute.

‘Just a minute, Larry. . . no more than a minute.’

I felt a stab of conscience. I had a pile of letters and orders in my In-tray I hadn’t looked at. The time was 15.00, and these letters and orders had been lying in my In-tray since 09.00.

‘I’ve got mail to look at, Sydney,’ I said. ‘Is it important?’

‘Yes.’

I got to my feet. As I did so, I looked across the showroom, where Terry was sitting behind his desk.

He was watching me, a sneering little grin on his handsome face. His In-tray was empty. Whatever else he was, Terry was a worker.

I followed Sydney into his office, and he shut the door as if it were made of egg shells.

‘Sit down, Larry.’

I sat down.

He began to move around his big office like a moth in search of a candle.

To help him out, I said, ‘Something on your mind, Sydney?’

‘You are on my mind.’ He came to an abrupt stop and looked sorrowfully at me. ‘I want you to do me a very special favour.’

‘What is it?’

He began fluttering around the room again.

‘For God’s sake sit down!’ I snapped at him. ‘What is it?’

He shot to his desk and sat down. Taking out his silk handkerchief, he began to mop his face.

‘What is it?’ I repeated.

‘It’s not working out, is it, Larry?’ he said, not looking at me.

‘What’s not working out?’

He put his handkerchief away, got a grip on himself, placed his elbow

s on the polished surface of the desk and somehow forced himself to look directly at me.

‘I want you to do me a favour.’

‘You said that before, what favour?’

‘I want you to see Dr. Melish.’

If he had smacked my face I couldn’t have been more surprised. I reared back, staring at him.

Dr. Melish was the most expensive, most sought after head-shrinker in the city. Considering there is about one head-shrinker to every fifty citizens in this city, this is saying a lot.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I want you to see him, Larry. I’ll pick up the tab. I think you should see him.’ He raised his hands as I began to protest. ‘Wait a moment, Larry. Do give me time to say something.’ He paused, then went on, ‘Larry, you’re not as right as rain. I know the ordeal you have been through. I know your dreadful loss has done damage. This I can understand. If I had been in your place I just couldn’t have survived. I know it! I think you have been marvellous coming back here and trying, but it hasn’t worked. You know that, don’t you, Larry?’ He looked pleadingly at me. ‘You do know that?’

I rubbed the back of my hand against my chin. The rasp of stubble made me stiffen. Goddamn it! I thought. I’ve forgotten to shave this morning! I got to my feet and crossed the room to the big wall mirror in which Sydney so often admired himself. I stared at my reflection and I felt a cold qualm. Could this mess be me? I looked at my shirt cuffs and then at my shoes that hadn’t been polished for a couple of weeks.

Slowly, I returned to the chair and sat down. I looked at Sydney, who was watching me. I saw on his face his anxiety, his kindness and the tizz he was in. I wasn’t so far gone that I couldn’t put myself in his place. I thought of the mistakes I had made in the overflowing In-tray and how I was looking. For all the confidence I had in myself, for all the facade of bravery (can you call it that?) I just wasn’t - as he put it - as right as rain.

I drew in a long, deep breath.

‘Look, Sydney, let’s forget Melish. I’ll resign. You’re right. Something has gone wrong. I’ll get the hell out of here and you give Terry his chance. He’s okay. Don’t worry about me, because I’ve ceased to worry about myself.’

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

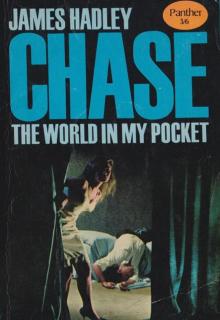

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

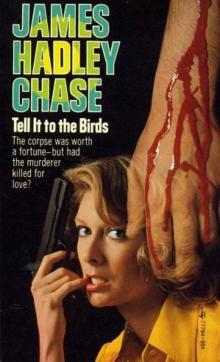

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

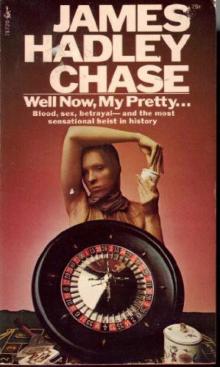

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

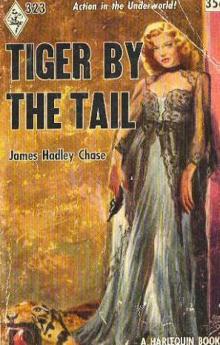

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail