- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1973 - Have a Change of Scene Page 2

1973 - Have a Change of Scene Read online

Page 2

‘You are the best diamond man in the business,’ Sydney said quietly. He was now fully in control of himself, and his buzzing and fluttering had stopped. ‘I’m not going to let you resign. I can’t afford to lose you. You want adjustment, and Dr. Melish can fix it. Now listen to me, Larry. In the past I’ve done a lot of things for you, and I believe you regard me as your friend. Now is the time for you to do something for me. I want you to see Melish. I know he can straighten you out. It may take two or three months. I don’t care if it takes a year. Your job with us will always be waiting for you. You are important people to me. Let me repeat: you are the best diamond man in the business. You have had a terrible knock, but it can be straightened out. This is the least you can do in return. see Melish.’

So I saw Melish.

As Sydney had said it was the least I could do, but I had no faith in Dr. Melish until I met him. He was small, thin, balding with penetrating eyes. He had been briefed by Sydney so he knew all about my background, about Judy and how I was reacting.

Why go into details? I had three sessions with him and he finally came up with his verdict.

It came down to this: I needed a complete change of scene. I was to get away from Paradise City for at least three months.

‘I understand you haven’t driven a car since the accident,’ he said, polishing his glasses. ‘You must get a car and you must drive. The problem with you is that you imagine your loss is something unique.’ He raised his hand, as I began to protest. ‘I know you don’t want to admit this, but all the same it is your problem. I suggest you mix with people who have bigger problems than you have. In this way, you will get your own problem in the right perspective. I have a niece who lives in Luceville. She does welfare work and she needs unpaid help. I’m suggesting you should go to Luceville and work with her. I have already talked to her. I will be quite frank with you. When I told her about you she said she wasn’t in the market for a disturbed person. She wants help badly, and if she has to cope with your difficulties she doesn’t want you. I told her you would help her and wouldn’t create any problems. It took me a little time to persuade her and now it is up to you.’

I shook my head.

‘I’d be as useful to your niece as a hole in the head,’ I said. ‘No that’s a dumb idea. I’ll find something. Okay, I’ll go away for three months. I’ll…’

He twiddled with his glasses.

‘My niece needs help,’ he said, staring at me. ‘Don’t you want to help people or have you decided people must continue to help you?’

Put like that I hadn’t a comeback. What had I to lose? Sydney was going to pay me while I was trying to get rehabilitated. I should be shot of the showroom with the sympathetic hushed voices and Terry’s sneering grin. Maybe this was an idea. At least it was something new, and how I yearned for something new!

Rather feebly, I said, ‘But I’m not qualified for welfare work. I know nothing about it. I would be more hindrance than help.’

Melish glanced at his wristwatch. I could see he was already thinking about his next patient.

‘If my niece says she can make use of you, then she can make use of you,’ he said patiently. ‘Why not give it a try?’

Why not? I shrugged and said I would go to Luceville.

My first move was to buy a Buick convertible. It took an effort of will to drive it to my apartment. I was sweating and shaking by the time I had parked. I sat at the wheel for some five minutes, then forced myself to set the car in motion and I drove along the busy main street, along Seaview boulevard, back into main street and then to my apartment. When I parked this time I wasn’t sweating and shaking.

Sydney came to see me off.

‘In three months’ time, Larry,’ he said as he shook hands, ‘you will be back and you will still be the best diamond man in the business. Good luck and God bless.’

So with a suitcase full of clothes, with no confidence in the future, I drove off to Luceville.

* * *

Dr. Melish could certainly claim credit for providing me with a change of scene.

Luceville, some five hundred miles north of Paradise City turned out to be a big straggling industrial town that dwelt under a permanent cloud of smog. Its main industry was limestone. Limestone, in case you don’t know, is crushed for lime, cement and building and road materials. It happens to be Florida’s main industry.

Driving slowly, it took me two days on the road to get to Luceville. I found I was now a nervous driver and every time a car swished by me I flinched, but I kept going, spending a night at a dreary motel and finally arriving at Luceville around 11.00, feeling drained and jumpy.

As I approached the outskirts of the town, cement dust began to settle on my skin, making me feel unwashed and gritty. It also settled on the windshield and on the car. There was no sun. No sun, however powerful, could ever penetrate the smog and the cement dust that hung over the town. Along the highway leading to the city’s centre were vast limestone factories and the noise of rock being crushed sounded like distant thunder.

I found the Bendix Hotel, recommended by Dr. Melish as the best in town, down a side street off Main Street. It was a sad affair; its glass doors were covered with cement dust, its lobby furnished with sagging bamboo chairs and its reception desk a mere counter behind which was a board with a row of keys.

A tall, overfat man with long side-whiskers dwelt behind the counter. He looked like a character who had got involved in a battle and was now licking his wounds.

He booked me in without fuss or interest. A sad-looking coloured boy took my bag and showed me to my room, overlooking a tenement block and on the third floor. We travelled together in an elevator that shuddered, creaked and jerked and I was thankful to arrive in one piece.

I looked around the room. At least it had four walls, a ceiling, a toilet and shower, but there was nothing else for it to boast about.

This was certainly a change of scene.

Paradise City and Luceville were as different as a Rolls-Royce is to a third-hand, beat-up Chevy - maybe that is insulting the Chevy.

I unpacked, hung my clothes in the closet, then stripped off and took a shower. Because I was determined to get to grips with myself, I put on a clean white shirt and one of my better suits. I looked at myself in the flyblown mirror and I felt a tiny surge of confidence. At least, I thought, I looked once again like someone in the executive bracket, maybe a little wan, but still, unmistakably someone with authority. It’s amazing, I told myself, what an expensive, well-cut suit, a white shirt and a good tie can do for a man, even such a man as myself.

Dr. Melish had given me his niece’s telephone number. Her name, he had told me, was Jenny Baxter. I called the number, but there was no reply. Slightly irritated, I prowled around the room for some five minutes, then tried again. Still no answer. I went to the open window and looked down at the street. There were a lot of people milling around: they all looked shabby, most of them dirty, most of them women, shopping. There were a lot of kids: they all looked in need of a bath. The cars that congested the streets were all covered with cement dust. I was to learn later that cement dust was the biggest enemy of this town: bigger than boredom that rated as enemy No. 2.

I called Jenny Baxter’s number again, and this time a rather breathless woman’s voice said, ‘Hello?’

‘Miss Baxter?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m Laurence Carr. Your uncle, Dr. Melish.’ I paused. She either knew about me or she didn’t.

‘Of course. Where are you?’

‘The Bendix Hotel.’

‘Will you give me about an hour? Then I’ll be over.’

In spite of her breathlessness - as if she had run up six flights of stairs, which I found out later was exactly what she had done - she sounded crisp and efficient.

I wasn’t in the mood to hang around in this dismal room.

‘Suppose I come over?’ I said.

‘Oh yes do that. You have the address?’

‘Then come as soon as you like,’ and she hung up.

I walked down the three flights of stairs. My nerves were still in a bad shape and I couldn’t face the creaking elevator. I asked the coloured boy directions. He said Maddox Street was a five-minute walk from the hotel. As I had found parking for my car after a struggle, I decided to walk.

As I walked down Main Street I became aware that people were staring at me. It gradually dawned on me they were staring at my clothes. When you walk down Main Street, Paradise City, you come up against competition. You just had to be well dressed, but here, in this smog-ridden town, everyone seemed to me to be in rags.

I found Jenny Baxter in a tiny room that served as an office on the sixth floor of a shabby walkup block. I toiled up the stairs, feeling cement dust gritty around my collar. A change of scene? Melish had certainly picked me a beauty.

Jenny Baxter was thirty-three years of age. She was tall: around five foot nine, dark with a mass of untidy black hair pinned to the top of her head and that seemed to be threatening to fall down at any moment. She was lean. By my standards, her figure was unfeminine: her breasts, unlike those of the women I knew in Paradise City, were tiny mounds and sexually uninteresting. She looked slightly starved. She was wearing a drab grey dress that she must have made herself: there could be no other explanation for its cut and the way it hung on her. Her features were good: her nose and mouth excellent, but what hooked me were her eyes. Her eyes were honest, interesting and penetrating like those of her uncle.

She was scribbling on a yellow form as I came into the tiny room, and she looked up and regarded me.

I stood in the doorway, unsure of myself, wondering what the hell I was doing here.

‘Larry Carr?’ Her voice was low toned and rich. ‘Come on in.’

As I moved in, the telephone bell started up. She waved me to the only other chair, then took up the receiver. Her replies, consisting of ‘yes’ and ‘no’, were crisp and impersonal. She seemed to have the technique of cutting off what could have been a lengthy conversation had she not been able to control the speaker.

Finally, she replaced the receiver, ran her pencil through her hair and smiled at me. The moment she smiled she became a different person. It was a wonderful, open smile of warmth and friendliness.

‘Sorry. This thing never stops ringing. So you want to help?’

I sat down.

‘If I can.’ I wondered if I really meant this.

‘But not in those beautiful clothes.’

I forced a smile.

‘No, but don’t blame me. Your uncle didn’t warn me.’

She nodded.

‘My uncle is a wonderful man, but he doesn’t bother with details.’ She leaned back and regarded me. ‘He told me about you. I believe in speaking frankly. I know about your problem, and I’m sorry about it, but it doesn’t interest me, because I have hundreds of my own problems. Uncle Henry told me you want to get straightened out, but that is your problem, and in my thinking, it is up to you to straighten yourself out.’ She put her hands on the soiled blotter and smiled at me. ‘Please understand. In this dreadful town there is a lot of work to do and a lot of help to be given. I need help and I haven’t time for sympathy.’

‘I’m here to help.’ I couldn’t keep the resentment out of my voice. Who did she imagine she was talking to? ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘If I could only believe you really are here to help,’ she said.

‘I’m telling you. I’m here to help. So what do I do?’

She took from a drawer a crumpled pack of cigarettes and offered it.

I produced the gold cigarette case Sydney had given me for my last birthday. It was rather special. It had set Sydney back $1,500: a cigarette case I was proud of: call it a status symbol if you like. Even some of my clients gave it a double take when I produced it.

‘Have one of mine?’ I said.

She looked at the glittering case and then at me.

‘Is that really gold?’

‘This?’ I turned it in my hand so she could see every inch of it. ‘Oh, sure.’

‘But isn’t it very valuable?’

The cement dust felt a little more gritty around my neck.

‘It was a present, fifteen hundred dollars.’ I offered it. ‘Do you want to smoke one of mine?’

‘No, thank you.’ She took a cigarette from her crumpled pack and dragged her eyes away from the cigarette case. ‘Be careful with that,’ she went on. ‘It could be stolen.’

‘They steal things here?’

She nodded and accepted a light from my gold lighter one of my clients had given me.

‘Fifteen hundred dollars? For that amount of money I could supply ten of my families with food for a month.’

‘You have ten families?’ I put the cigarette case back into my hip pocket. ‘Really?’

‘I have two thousand five hundred and twenty-two families,’ she said quietly. She opened a drawer in her battered desk and took from it a street plan of Luceville. She placed it on the desk so I could see it.

The plan had been divided up into five sections with a felt pen: each section was marked from 1 to 5.

‘You should know what you’re walking into,’ she went on. ‘Let me explain.’

She went on to tell me there were five welfare workers in the town: all professionals. Each had a section of the town to look after: she was in charge of the dirtiest end of the stick. She glanced up and smiled. ‘No one else wanted it, so I took it. I’ve been here for the past two years. My job is to give help when help is genuinely needed. I have a fund which is far from adequate to draw on. I visit people. I make reports. The reports have to be broken down and put on cards.’ She tapped No. 5 section on the plan. ‘This is my beat. It contains probably the worst of the worst in this dreadful town: close on four thousand people, including kids who are no longer kids after they are seven years old. Out here.’ Her pencil moved from the ringed section of No. 5 and tapped just beyond the town’s boundary, ‘is the Florida Women’s House of Correction. This is a very tough prison: not only are the prisoners tough, but the conditions are tough: most of them are long term and a lot of them hopeless criminals. Up to three months ago, prison visitors weren’t allowed, but I’ve finally convinced the people concerned that I can be helpful.’ The telephone bell rang and again she went through her crisp ‘yes’ and ‘no’ routine and hung up.

‘I am allowed one unpaid helper,’ she went on as if the telephone conversation hadn’t happened. ‘People do volunteer as you have volunteered. Your job would be to keep the card index straight, take care of the telephone, handle any emergency until I can fix it, type my reports if you can read my awful handwriting. In fact, you will hold everything down until I can get back to this desk and hold it down myself.’

I shifted in the uncomfortable chair. What the hell was Melish thinking of, or didn’t he know? She didn’t want a man with my background, she wanted an efficient girl who could cope with office work.

This was strictly no job for me.

I told her so as politely as I could, but I couldn’t keep the resentment out of my voice.

‘This is not a job for a girl,’ Jenny said. ‘My last volunteer was a retired accountant. He was sixty-five years of age with nothing to do except play golf and bridge. He jumped at the chance to help me, and he lasted two weeks. I didn’t blame him when he quit.’

‘You mean the job bored him?’

‘No it didn’t bore him. He became frightened.’

I stared at her.

‘Frightened? You mean there was too much work for him to do?’

She smiled her warm smile.

‘No. He was a glutton for work. He did a marvellous job while he lasted. For the first time my records were really straightened out. No he couldn’t take what came in through that door from time to time,’ and she nodded at the door of the tiny office. ‘You had better know, Larry, there is a ga

ng of kids who terrorise this section of the city. They are known to the police as the Jinx gang. Their ages run from ten to twenty years. There are about thirty of them. The leader is Spooky Jinx - that’s what he calls himself - he imagines he is a Mafia character. He is vicious and extremely dangerous and the other kids follow him slavishly. The police can’t do anything about him: he’s far too smart. They have picked up quite a few of the gang, but never Spooky.’ She paused and then went on, ‘Spooky has the idea that I am prying. He thinks I give information to the police. He thinks all the people I try to help should get on without my help. He and his gang regard their parents as creeps because they accept the handouts I can arrange for them: milk for the babies, clothes, coal and so on and so on and because I help them with their problems like how they can pay their rent, about their hire purchase all their troubles they share with me. Spooky thinks I interfere, and he makes my life difficult. Every so often they come here and try and frighten me.’

Again the warm smile. ‘They don’t frighten me, but up to now they have succeeded in frightening my voluntary helpers.’

I listened, but I didn’t believe. Some kid this didn’t make sense to me.

‘I don’t think I’m quite with you,’ I said. ‘You mean this kid scared your accountant friend and he quit? How did this kid do that?’

‘He’s very persuasive. You must remember that this job is unpaid. My accountant friend explained it all to me. He is no longer young. He didn’t think the job was worth the threat.’

‘Threat?’

‘The usual thing - if he didn’t quit they would find him one dark night. They are vicious.’ She regarded me, her face suddenly grave. ‘He has a wife and a nice home. He decided to quit.’

I felt a sudden tightening of my belly. I knew all about delinquent kids. Who hasn’t read about them?

A dark night and suddenly to be set upon by a bunch of little savages: no holds barred. A kick in the face could lose a set of decent teeth. A kick in the groin could make a man impotent.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

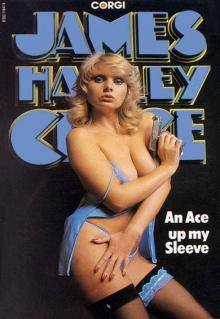

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

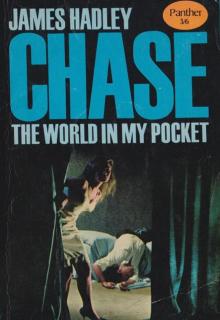

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

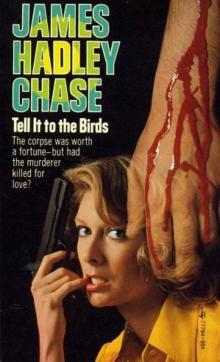

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

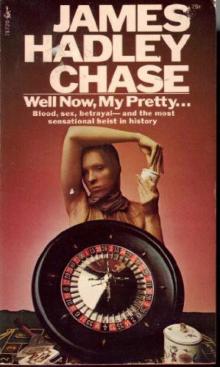

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

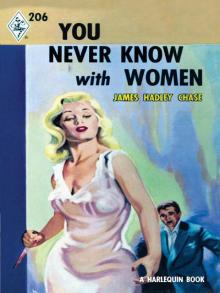

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

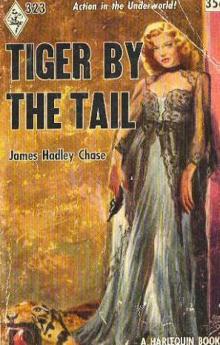

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail