- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway Page 9

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway Read online

Page 9

‘I want to talk to you,’ she said out of the darkness.

‘I’m good at listening.’ His voice was scarcely a murmur. ‘Go ahead . . . talk.’

She dropped the cigarette. It fell on the sand, its glowing tip flared, then died.

‘We can’t talk here.’ He was aware her voice was husky and breathless ‘Come with me . . . give me your hand.’

He felt a sense of sharp disappointment. Her rage and her contempt had been important to him. You cowardly thug. She had called him that. Calling him that had been at least something different which he had welcomed: something completely different from the sickening love names he had been called by the sex-starved women who had groaned and squirmed under him, their fingernails digging into his back.

He put out his hand. In the darkness, she failed for a moment to find contact, then her dry, burning fingers closed around his wrist. Leading him, she moved off into the darkness. He went without eagerness, but without hesitation. His heart seemed to be beating more slowly and with difficulty as if his blood had thickened.

Finally, they reached a clump of palm trees, surrounded by sand dunes: a narrow channel between the dunes gave them a direct view of the sea which looked like a black mirror as it reflected the moon.

She released his hand and dropped down on her knees: there was now enough light for him to see her distinctly. Her scarlet pyjamas appeared to be black; her skin sharply white by contrast. He stood beside her, looking down at her. Impatiently, she caught hold of his hand and pulled him down so he too was kneeling, facing her.

‘That was the most beautiful thing that has ever happened to me,’ she said fiercely, ‘when you knocked that fat old swine off his feet.’

He felt a tiny explosion of shock inside him. This was the last thing he was expecting to hear from her. He stiffened, resting his clenched fists on his thighs.

‘If you knew the times I had hoped and prayed that some man would do it,’ she went on. ‘If you could know how much I needed proof that he really wasn’t the godhead and wasn’t utterly invincible as he told my mother, told my brother and told me until we began to believe it. I watched you play with him. Three times you let him hit at you. Then . . .! It was the most beautiful, satisfying thing that has ever happened to me!’

Still he said nothing: still he stared at her.

‘I hate him!’ The passionate vehemence in her voice made him flinch. ‘He is crushing me and ruining my life as he ruined my mother’s life, as he tried to ruin Sam’s life. But Sam had the guts to clear out and join the army. He looks on me as his chattel as he looked on mother as his chattel: a neuter creature who must have no feelings, no thoughts, no ambitions: who must never have a husband nor a lover. If I hadn’t told him I wanted you to go, he would never have let me out of his sight so long as you remain here. But I’ve fooled him! He really believes I hate you because you knocked him down. You are the first real man, after Sam, who has come here. Others have come and gone: too scared even to look at me.’

‘Why are you telling me all this?’ Harry asked.

‘Because you are a man and I want a man,’ she said.

With two rapid movements, she took off her pyjama top and trousers. He could hear her breath rasping against the back of her throat as she leaned forward and began to unbutton his shirt.

He pushed her hands away, hesitating. Then his desire for her, almost as frantic as her own for him, overrode his caution. He stripped off and took her.

She nearly spoilt it for them both by her raging impatience, but he held her firmly, crushing her so she couldn’t move, speaking gently to her, his face against hers, telling her to wait, that it must be slow. After a few moments when she reared against him, she seemed to sense that he knew what was best for her and she became relaxed and still. It took him many long minutes before he knew by her quick breathing and by the way she began to arch her back that she was ready for the storm.

He said softly to her, ‘Yes . . . now . . . together.’

And then came the great rushing surging waves, the roaring in their ears and the floating into a vacuum that they wanted to go on forever.

* * *

As Randy approached Harry’s cabin he saw a light from behind the curtain. He paused before the door and knocked. He heard Harry cross the room, then the door opened.

‘Come on in.’

‘Keep your voice down,’ Randy said softly. ‘Manuel’s just gone to bed.’

‘Then we’ll take the case to your cabin.’ Harry crossed to the bed and picked up the white plastic suitcase.

‘What’s inside?’

‘I haven’t looked yet . . . it’s locked. Have you a screwdriver?’

Randy peered at the locks.

‘I have a good knife . . . that should do it.’

They moved out into the hot night, walked the few yards down the path and entered Randy’s cabin. Randy put on the light, closed and bolted the door.

‘What have you been doing all this time?’ he asked. ‘I thought you were certain to have looked inside by now.’

‘I was waiting for you. If there’s any money in here, it’s not a lot’

Randy opened a drawer in his chest, took out a broad-bladed fishing knife and offered it. It didn’t take Harry long to force open the catches of the case. Then he lifted the lid.

Breathing heavily, Randy stood over him, watching.

Carefully, Harry laid the contents of the suitcase out onto the bed. Then he moved the case off the bed and surveyed the articles from the case laid out now in two neat rows.

There was a grey, shabby lightweight suit, three white shirts, four pairs of black socks, a shabby plastic hold-all containing a cordless razor, tooth brush, sponge, soap and a tube of dentifrice, a pair of blue pyjamas, well-worn heelless slippers and six white handkerchiefs. The second row offered more interest.

There was a 7.67 mm. Luger Automatic pistol with a box of one hundred cartridges, a hundred Chesterfield cigarettes, a half bottle of White Horse whisky, a small roll of $5 bills and a well-worn black leather wallet.

Harry picked up the roll of bills, slid off the elastic band and counted them.

‘Here’s our fortune, Randy. Two hundred and ten dollars.’

‘Better than nothing.’ Randy couldn’t keep the disappointment out of his voice.

Harry sat on the bed and picked up the wallet. He shook out its contents. There were several visiting cards with names of men that meant nothing to him: an American Express Credit card made out to Thomas Lowery; a $100 bill and a driving licence made out to William Riccard with a Los Angeles address.

Harry showed the licence to Randy.

‘At least we know for sure the dead man is Baldy Riccard.’

‘Where does that get us?’

Harry was staring at the articles on the bed.

‘There’s not one thing here that would be worth the torture Baldy endured,’ he said, half to himself, ‘and yet I’m willing to bet he was determined to keep this suitcase from changing hands.’ He picked up the empty suitcase, opened it and taking up Randy’s knife, he began slitting open the cloth lining. He discovered, fixed by adhesive tape to the lid, a plastic visiting card holder containing one plain card. He freed the card, turned it over and read the inscription written in small neat handwriting: The Funnel. Sheldon. It. 07.45. May 27.

‘This must be it . . . but what does it mean?’ Harry handed the card to Randy, Randy read it, then shook his head.

‘The only Sheldon I know is the Sheldon Island, ten miles outside the reef in the bay. Couldn’t be that or could it?’

‘What happens there?’

‘Nothing. It’s just rocks and birds. Nina goes out there when she wants to swim bare.’

‘The Funnel mean anything?’

‘Not to me . . . Nina might know. Shall I ask her?’

‘No.’ Harry took the card. He regarded it for a long moment, then shrugged and put the card in his shirt pocket. ‘Let’s get some sleep. It’s

getting late.’ He split the roll of $5 bills and offered half to Randy. ‘That’s your share.’

‘Gee! Thanks! I can use it.’ Randy waved to the articles on the bed. ‘What are you going to do with this junk?’

‘Get rid of it.’ Harry began packing the suitcase.

‘So that’s that . . . no fortune,’ Randy said. ‘What a letdown I . . .’

‘We don’t know yet . . . the card could be the clue.’ Harry closed the lid of the case and forced the catches back into their slots.

Watching him, seeing the far away expression in the blue eyes. Randy wondered what was going on in his mind.

‘See you tomorrow,’ Harry said. He picked up the suitcase and let himself out of the cabin.

Chapter Five

The only sound to disturb the silence that hung over the Detectives’ room at Paradise City Police Headquarters was the busy tapping of a bluebottle fly as it banged itself against the dirty ceiling.

Detective 3rd Grade Max Jacoby sat at his desk studying Assimil’s French Without Toil. He was silently mouthing sentences like: Le pauvre diable est sourd comme un pot and il est malin comme un singe.

Jacoby, young, tall and dark-complexioned had reached Lesson 114. He now had only 26 more lessons to complete the course. In anticipation of this event, he had saved up enough money to go to Paris for his summer vacation when he was determined to startle the Parisians with his knowledge of their language.

Opposite him, Sergeant Joe Beigler sat at his desk, a carton of lukewarm coffee in his hand, a cigarette drooping from his lips, his eyes half closed while he tried to make up his mind which horse he should back for the 15.00 hr. handicap.

A big, powerfully built man in his late thirties, his fleshy face freckled, Beigler was Captain of Police Frank Terrell’s right hand man. This afternoon, for a change, there was no immediate crime in the City. It had been so quiet, Terrell had gone home to mow his lawn leaving Beigler to hold the desk. Beigler was so used to this chore that he wouldn’t have known what to do with himself if he was given the afternoon off. So long as he had a constant supply of coffee and cigarettes, he would be content to remain at his desk until he was carried out to his funeral.

‘Would you say a monkey is a sly animal, Sarg?’ Jacoby asked, having puzzled over his lesson for some time, overlooking the fact that Assimil was hopefully offering him an addition to his vocabulary and not making insinuations against monkeys.

Only half hearing, Beigler lifted his head and squinted at Jacoby through the spiral of smoke from his cigarette.

‘What was that again?’

‘Il est malin comme un singe,’ Jacoby read with an excruciating accent. ‘Malin . . . sly. Singe . . . monkey. That’s what they say here. What do you think?’

Beigler drew in a long, slow breath. His freckled face turned a tomato red.

‘Are you calling me a goddamn monkey?’ he demanded, leaning forward aggressively.

Jacoby sighed. He should have known he couldn’t expect help or encouragement from Beigler whom he regarded as practically illiterate.

‘Okay, Sarg, forget it. Sorry I spoke.’

The door burst open and Detective 2nd Grade Lepski came into the room like a bullet from a gun. He slid to a standstill before Beigler’s desk.

‘The Chief in, Joe?’ he demanded, his voice loud and breathless.

Beigler sat back and eyed Lepski’s excited face with disapproval.

‘No, he isn’t. If you must know, he’s home cutting his lawn.’

‘Cutting his lawn?’ Lepski looked shocked. ‘You mean he’s using a goddamn power mower for God’s sake?’

‘No. He’s cutting it with a pair of nail scissors,’ Beigler said with heavy sarcasm. ‘That way he gets more suntan.’

‘Look, cut out the jokes.’ Lepski began to hop from one foot to the other. ‘I’m onto something hot. This could be my break, Joe . . . the break I’m waiting for for my promotion. While you punks have been sitting on your fannies, chewing the fat, I’ve found Riccard’s car!’

Beigler leaned forward.

‘Are you calling me a punk, Lepski?’

In spite of his excitement, Lepski realised he had slid onto thin ice. After all, Beigler was the Top Shot at Headquarters when the Chief wasn’t there. A slip like that could delay his promotion.

‘Listen, Sarg, when I talk about punks, I mean the rest of this dim crew like him.’ Lepski pointed to Jacoby. He was on safe ground here. Jacoby was only 3rd Grade. ‘Chiefs and Sergeants are always excluded. I’ve found Riccard’s car!’

Beigler scowled at him.

‘Well, don’t set it to music. Write a report.’

‘If the Chief is at home, I’d better go down and see him,’ Lepski said. He hated writing reports. ‘He’ll want to know about this, Sarg, pronto.’

Beigler decided Young Hopeful at 18 to 1 could be a slight risk but a fair chance and he wrote the name down on his blotter. He looked at the wall clock, saw he had another half hour before laying his bet and switched his mind back to police business.

‘Stop jumping about like you have a stoppage,’ he said. ‘Where did you find the car?’

‘Look, Sarg, we’re wasting time. I’d better talk to the Chief.’

‘I’m the Chief,’ Beigler said in an awful voice. ‘Right now I’m in charge of this goddamn force. Where did you find it?’

‘Look, Sarg, this is important to me . . .’

‘Where did you find it?’ Beigler roared, banging his fists on his desk.

Lepski saw it was hopeless.

‘I’ll write a report.’ He started towards his desk.

‘Come back here! You’ll write the report later. Where did you find it?’

‘It was found in the car park behind Mear’s Self-Service Store,’ Lepski said reluctantly.

‘It was found? Does that mean you didn’t find it personally?’

‘A patrolman found it,’ Lepski said sullenly. ‘I had the bright idea of calling Miami . . . so in actual fact I did find it.’

‘Go write the report,’ Beigler said. He dropped his big freckled hand on the telephone receiver, talked to Miami’s police headquarters as Lepski, his face sullen, began hammering away at his typewriter.

Beigler asked questions, grunted, asked more questions, then said, ‘Okay, Jack. We’ll want the full coverage. I’ll get Hess over to you. There’s talk around that Baldy has been knocked off . . . Yeah . . . okay,’ and he hung up.

He dialled Terrell’s home number. There was a little delay before Captain of Police Terrell came to the phone.

‘Riccard’s car has been found, Chief,’ Beigler said.

Lepski stopped typing and pointed frantically to himself, but Beigler ignored him.

‘The Miami police are checking it for fingerprints. I’m sending Hess there. Okay, Chief, I’ll keep in touch,’ and he hung up.

‘I didn’t hear you mention my name,’ Lepski said bitterly.

‘I didn’t,’ Beigler returned. ‘Get that report written!’ He swung his eyes to where Jacoby was still mouthing sentences.

‘Max! Take a car, go to Fred’s place, pick him up and take him to Mear’s Self-Service Store.’

‘Okay, Sarg.’ Jacoby put his books away hurriedly and charged out of the room.

‘Hess at home cutting his lawn too?’ Lepski asked bitterly.

‘His boy is sick. He’s taken the afternoon off.’

‘That two headed little monster? Sick? That’s a laugh? That little horror couldn’t be sick if he wanted to. It’s my bet Hess is snoring his head off in the sun.’

Beigler grinned.

‘You could be right . . . get on with that report.’

Ten minutes later, Lepski ripped the sheet out of the typewriter, read through what he had written, signed it with a flourish and laid it on Beigler’s desk.

‘I’ve got an idea,’ he said. ‘Danny O’Brien served five years with Baldy and Dominico. Suppose I go along and twist his arm a little? He might know w

hat Baldy was doing when he was here for three days.’

Beigler read the report, then looked up at Lepski.

‘You think Solo is lying?’

‘Of course he’s lying, but he’s too big and smart for us to twist his arm. I’m as sure as I’m standing here Baldy called on him and I want to know why. If anyone can tell me it’s Danny.’

Beigler rubbed his thick nose.

‘Well, okay. Go talk to him.’

Lepski eyed him.

‘If I were a Sergeant and read that report, do you know what I would think?’

‘Sure,’ Beigler said promptly. ‘You’d think it was written by a mental defective who had got to 2nd Grade by nepotism.’

Lepski gaped at him.

‘What was that again . . . nepot . . . what?’

Beigler was a great reader of paperbacks. When he came across a word he didn’t understand - and there were many of them – he looked them up in a dictionary and filed them away in his memory to use to impress. He savoured his triumph now by looking insufferably superior as he repeated, ‘Nepotism . . . favouritism to relatives in bestowing office.’

He was on safe ground here because Lepski’s wife happened to be a second cousin of Carrie, Captain Terrell’s wife. Beigler never ceased to pull Lepski’s leg about this knowing full well that the only difference the relationship made was to make Lepski mad.

‘When I become Chief of Police in this goddamn City,’ Lepski said heatedly, ‘I’ll have you retired. Don’t forget that!’

‘When you become Chief of Police of this City, Lepski, I’ll be the tenth man on the moon! Get the hell out of here and get working!’

Lepski drove to Seacombe, a suburb of Paradise City where the workers lived: a small, shabby colony of bungalows and tenement buildings, which spoilt the approach to the opulent, flower-laden millionaire’s playground.

Danny O’Brien lived in a two-room cold-water apartment on the sixth floor of a sordid tenement block overlooking the sea. At one time he had been a thriving coiner, specialising in making coins of the Roman era B.C. He had made considerable sums of money, selling these fakes to art collectors: his sales talk had been as impressive and as convincing as his forgeries. But he had become overambitious in his old age and had attempted to sell a Caesar gold piece to the Washington Museum who had unkindly handed him over to the police. Now, Danny made lead soldiers which he painted in exquisite colours and sold to a speciality toyshop that catered for elderly clients wishing to fight great battles of the previous century.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

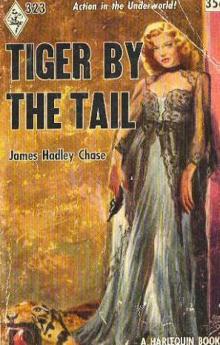

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail