- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Page 8

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Read online

Page 8

It was an effort to get the words out.

‘I don’t care what she’s doing. I said tell her to come here.’

‘I’ll tell her.’

I went down the dark passage to the kitchen, choking with rage. Was I never to get her alone for five minutes?

She was preparing supper, a bored, sullen expression on her face.

‘He wants you.’

She looked at me and smiled. It was the first time she had ever smiled at me, but it gave me no joy. It was a mocking, jeering little smile that sent the blood to my face.

‘You are having bad luck, aren’t you?’

‘Tonight. Do you hear? Come to my room tonight or I’ll tell him. I’m fed up with this. If you don’t come, I’ll tell him.’

She laughed.

‘I don’t think he’ll let me come. Now you’ve scared him out of his wits, he’s decided to sleep with me.’

I caught hold of her wrist, digging my nails into her flesh.

‘You’ve got to manage somehow...’

‘Careful,’ she said, and leaned against me. ‘He’s coming.’

I just had time to step away from her when he came in.

‘I won’t be left alone. Every sound I hear frightens me. Go and look round. Is what I pay you for.’

‘I’m going.’

I went out into the darkness, feeling the touch of her breast still against my arm and the soft, cool feel of her flesh in my hand.

What a fool I had been to have sent that note, I saw now how smart she was. She had gauged his cowardice. Her notes that I thought were tripe were just strong enough to make him jittery, but mine, I had been so proud of, had turned him into an uncontrollable pest.

So he was going to sleep with her. It made me sick to think of it. I knew there would be no sleep for me that night.

I went into the barn with her jeering little laugh still ringing in my ears.

The next morning began on the same lines as the previous morning. Sarek got up about seven o’clock and clung around me, never leaving me for a moment.

After an almost sleepless night, my nerves were ragged, and it was as much as I could do not to hit him. And to make it worse I knew she thought the situation was funny. Whenever she came into the room and found us together, her jeering little smile was like a flick of a whip.

Then just after ten o’clock, the telephone bell rang. I knew who it was, and when he told me Emmie was on her way down I suddenly felt ten years younger.

‘Shall I meet her?’

‘Is all right. I told her to take a taxi.’

I was grinning now. They would shut themselves up in the sitting room for at least a couple of hours, and I’d be free to tackle her.

She was in the room when Emmie rang and I looked at her. It was my turn to jeer at her now. She didn’t meet my eyes, and the sullen look of indifference had returned to her face.

This was going to be the show down, and she knew it.

Emmie arrived around noon. It was the longest morning I have ever lived through. I never thought I would be glad to see that squat, fat figure, but I was. I could have cheered when I saw her squeezing herself through the door of the taxi, showing her legs that had no more shape to them than tree stumps.

I had gone into the barn to chop wood, leaving Sarek with Rita, and I watched the taxi’s arrival from the barn door.

As soon as she had waddled into the house I slung down the axe. I’d give them five minutes to settle down to business, then I’d go and find Rita.

I lit a cigarette with a hand that shook like a leaf, and looked through the doorway at the house, counting the uneven beats of my heart.

I caught a glimpse of Sarek through the window. He was pulling up a chair to the fire. Then Emmie came into view for a moment as she crossed the room to join him.

I couldn’t wait another second. Throwing the cigarette away, I started towards the barn door.

She was in the doorway, facing me.

How she got there I didn’t know or care. There she was, in her grey sweater and slacks, her hands on her hips, looking at me.

For perhaps four or five seconds we stood motionless, like a couple of waxworks. There was in expression in her eyes I had never seen before. There was no jeer in her smile either.

‘Were you coming to me?’

‘You know I was.’

My voice sounded as if I was being strangled.

‘Don’t look like that. It’s all right, Frank. Before it just wasn’t safe.’

I wasn’t aware she had moved close to me; suddenly her face was within six inches of mine.

I grabbed her.

I felt her fingers at the back of my neck, pulling my head down. My mouth covered hers. Her hands slid from my head to my shoulders, her fingers like hooks digging into my back muscles. I felt her breath against the back of my throat.

We stayed like that for maybe a minute, then I swung her off her feet and carried her over to the pile of hay in the darkest comer of the barn.

‘The door... shut it, Frank.’

‘To hell with the door...’

I dropped her on the hay and I melt over her.

‘No! Don’t be a fool! She might come out here.’

‘To hell with her!’

‘See what they’re doing.’

I walked across the uneven floor of the barn to the door, and leaned against the barn doorway and looked towards the house. Through the lower window I could see the sunlight reflecting on Sarek’s baldhead. He was still there, before the fire. ‘It’s all right. They’re still talking.’

‘Stay there and watch them. If he saw us together. . .’

‘What’s got into you? This is a pretty sudden change, isn’t it? I thought you couldn’t stand the sight of me.’

I heard her quiet laugh and turned my head to look at her. She was lying half-hidden in the hay, her arms above her head one leg drawn up.

‘I fell for you the moment I saw you. I like big men.’

‘I don’t believe it! Not after the way you’ve been treating me. You’ve driven me crazy.’

‘I’m glad. I like men to go crazy about me. But it wasn’t all that.’

‘Then what was it?’

‘When I saw the look in your eyes when we first met I knew this thing was going to happen; and I wanted it to happen. But I know him a lot better than you do. He’s insanely jealous. You wouldn’t have remained here three minutes if he thought you meant anything to me. Not three seconds. But it’s all right now: all right so long as we’re careful. He’s sure I haven’t any time for you. I’ve told him over and over again to get rid of you. He hasn’t an idea this could have happened.’

‘You damned near talked him into getting rid of me. If I hadn’t thrown a scare into hire . . .’

‘I had to do it. It was a risk I had to run. But if he had told you to go I would have sent him another note. Only you did it for me.’

‘You’re some actress. I still don’t believe it.’

‘Did you believe just now?’

‘Yes, I believed that all right. That wasn’t faked.’

‘Well then... don’t be so suspicious.’

‘You made me suffer.’

‘I’ve made up for it, haven’t I?’

‘Not yet; but it’s helped.’

Again she laughed.

‘The next time he goes to Paris I’m staying here - with you. You’ll believe it then?’

My heart began to pound again.

‘When’s he going?’

‘I don’t know. He usually goes every month.’

‘He’s just been. Do you mean I have to keep away from you for a month? Is that what you’re trying to tell me?’

‘There’s another way out of it.’

‘What’s that?’

‘We can kill him, Frank.’

The battered little milk van came rushing up the narrow lane. A hand came out of the van window and placed two-pint bottles of milk on the top of the gate

. Then the van reversed, swung in a half-circle, and stormed down the lane again.

The only time that milkman bothered to get out of his van was when he came to collect his money: no other time.

‘What was that? What did you say?’

‘We can kill him, Frank.’

I turned to stare at her. All I could see was the white column of her throat as she lay staring up at the dusty rafters, and the points of her breasts, hard against the soft wool of her sweater.

‘What kind of crazy talk is that?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. I was offering you another solution. I don’t suppose I was serious.’

‘You’d better not be serious!’

‘No?’

‘No!’

She raised her arm and looked at her wristwatch.

‘I must go in. I haven’t started the lunch yet.’

She scrambled to her feet, and began brushing the wisps of hay of her trousers.

‘Brush me down at the back, Frank.’

I went over and slapped the dust and hay from her legs, ‘Ow, you’re hurting!’

I jerked her to me.

‘They hang you for murder. Had you forgotten?’

‘Who’s talking about murder?’

‘Then what are you driving at?’

‘I’m not driving at anything. Perhaps his cold will get worse and he’ll die that way. It would be nice if he did die, wouldn’t it? Then you wouldn’t have to sleep in that little room and I wouldn’t have to give him a son.’

‘Shut up!’

I took her by her shoulders and shook her.

‘Shut up about that!’

Her eyes looked like emeralds in the half-light.

‘You don’t like the idea, Frank? Nor do I.’

She pulled away from me and went out of the barn.

Around bedtime he startled me by saying he was going to the office the next day.

‘I can’t afford to neglect my business. With you, I’ll be all right, hey?’

‘You’ll be all right.’

‘You’ll take the gun?’

‘Yes.’

He nodded, still a little fearful, but I could see he had made up his mind or fat Emmie had made it up for him.

‘Well, is all right then. I go to bed now.’

‘I’ll take a look round. I won’t be long in following you.’

‘Good night.’

I waited until he had gone up the stairs, then I slipped on my duffel coat and went out into the darkness. The air was crisply cold and the wind easterly. There was no moon, but the black sky was pinpointed with stars.

I groped my way to the barn and up into the loft. As soon as I pushed open the loft door I saw she hadn’t pulled down the blind. I sat on the floor, looking into her room, a tight feeling in my throat, and my heart pounding.

She was sitting before her dressing table, in the green silk wrap over an oyster-white nightdress.

I watched her brush her hair for five minutes, then the door opened and Sarek came in. He was wearing his dressing gown and pyjamas, and over his arm he carried his awful overcoat. He hung the coat on a hook behind the door, took off his dressing gown and got into bed.

She didn’t look round, but continued to brush her hair. I could see him speaking to her, frowning, pointing to the window.

She gave an impatient little shrug and came to the window.

We looked at each other across the dark space. I knew she couldn’t see me, but I knew she knew I was there.

I watched her pull down the blind. I saw her shadow move towards the bed, then the light went out and I was looking at nothing, feeling the pain of frustration and jealousy enter into me like the slow thrust of a sword.

For the next seven days I had no chance of being alone with her. Sarek and I went to the office every day and returned in the evening. He wouldn’t let me out of his sight except when I went to lock up the chickens and take the last look round, and then he’d only let me go if she stayed with him.

Every night she left the blind up, and I watched her prepare for bed. And when Sarek joined her, the last thing she did before pulling down the blind was to look towards the bam.

By the end of the seventh day I wasn’t sure if I was in my right mind.

‘We can kill him, Frank.’

I had never ceased to think about that. At first I thought she had been joking, then I decided she had been serious, and it worried me. But at the end of the seventh day I was wanting to kill him myself.

Watching him night after night in her room, put a kink in my brain.

‘We can kill him, Frank.’

It meant nothing to me now - nothing. As if she had said we’d kill a cockerel for dinner: not as much.

On the tenth night I nearly did kill him.

I was up there in the loft, watching her undress when he came into the room. She didn’t look at him or pay him any attention, and he stood watching her for a moment. Then he reached out and touched her.

I had the gun in my hand. I was aiming at him, swearing aloud, raving like a madman, the gun sight steady as a rock, my finger taking up the trigger slack. Then she moved between the gun sight and his head and I dropped the gun with a shudder to the floor.

I had nearly murdered him. If she hadn’t moved at that moment I would have shot him: as close to murder as that.

On the way to the office the next morning, he told me casually that tomorrow he would catch the ten o’clock plane to Paris.

chapter nine

It was just after seven and I was lighting the fire when he came in. One look at his face told me something had happened. He was beaming: I don’t think I have seen anyone look as happy as he did, and I gaped at him.

‘Mrs. Sarek she is sick this morning.’

My mouth went dry.

‘You mean she is ill?’

He patted me on the shoulder. If possible his grin seemed to widen. I could see every tooth in his head.

‘No; not ill; is sick, you understand? Very sick. Is first sign, hey? Sick in the morning is good, hey?’

I didn’t say anything: I couldn’t.

He took out his handkerchief and polished his great, hooked nose. It gave him also the opportunity to wipe his eyes.

He was nearly blubbering.

‘Is what I pray for. I wait three year for this. Is my son coming.’

I turned my back squarely on him and poked the fire. If he had seen my face, he would have known the set-up. I felt bad enough to faint. But he was far too busy being happy to notice anything wrong with me.

‘Is too sick to fly this morning. She want to stay here. Is understandable. I’ll be back in three, four days.’

I felt the blood return to my face. She had told me she would stay the next time he went to Paris. Maybe the sickness was a blind. I hoped so.

‘Well, you won’t want me around here, Mr. Sarek. I’ll spend a few days in London unless you want me with you in Paris.’

He beamed at me.

‘Is right. You take a few days of. Have a good time. I never ask you, Frank. You got a girl, hey?’

‘Well, yes. She’ll be glad to see me.’

‘You get married soon?’

I shook my head.

‘I’m not the marrying type.’

He patted my shoulder.

‘You think about marriage, Frank. Is good to have a son.’

I grinned at him. There wasn’t much heart in it.

‘I’d rather have a rich father.’

While I was supposed to be getting the car out of the garage, I heard him phoning Emmie. He was telling her about his son, and from the way he talked she wasn’t over-excited.

‘I feel it,’ he said saying aggressively. ‘Is a son coming. I know. Is no good you saying things like that. I don’t listen. I know, I tell you.’

I had hoped to sneak up the stairs and find out if it had happened or if she was fooling him, but I didn’t get the chance.

The sitting room looked on to

the stairs, and the door was open while he telephoned.

I went out and got the car.

After a while he came down the path, wrapped in his comic coat, grinning from ear to ear. He climbed in, beside me, and we started off.

All the way to the airport he talked about his son-to-be, what he was going to do with him, where he was going to educate him, and a lot of stuff like that that nearly drove me nuts.

‘Don’t count your chicken, Mr. Sarek. Maybe you’ll get a girl.’

‘Is son. I know is son. Don’t talk to me about girls. Is unlucky.’

Miss Robinson was there to welcome him, and of course he had to tell her.

‘Excuse me, Mr. Sarek, but if you don’t want me any longer I’ll get off. You’re in good company.’

‘Is all right. You get off.’

He went right on talking to Miss Robinson.

I heard her say, ‘I’m terribly glad for you, Mr. Sarek. I know how you want a boy. I do wish you luck: you and Mrs. Sarek.’

And she really made it sound as if she meant it.

I returned to the car and headed back to Four Winds. On Western Avenue I beat the old crock up to seventy-three. It bounced about the road like a crazy kangaroo, but I kept it at it: I wanted to get back, and get back fast.

When I reached the house I shoved the car into the garage and locked the door. I wasn’t supposed to go back, and I wasn’t taking any chances of a tradesman seeing me and talking. Then I unlocked the front door and walked into the sitting room.

She was kneeling before the fire, still in her dressing gown. She looked over her shoulder at me and smiled. There were shadowy smudges under her eyes, and her face was pale, but there was nothing wrong with her smile.

‘Were you sick?’

‘I was sick all right. I ate soap.’

I grabbed her and hauled her to her feet, ‘Then it isn’t true?’

‘Do you think I’d carry a child of his?’

‘But he thinks it’s coming. He’s acting like a crazy man telling everyone. He’s even told that air hostess.’

‘How was I to know the fool would jump to that conclusion? I had to be ill or he would have made me go with him.’

‘Did you have to be sick?’

‘You don’t know him like I do. He has to have proof. A headache or a pain wouldn’t have done.’

I suddenly saw how funny it was and began to laugh.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

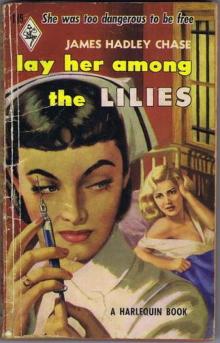

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

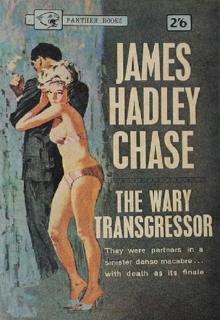

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

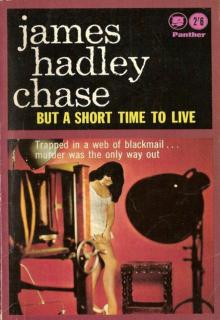

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail