- Home

- James Hadley Chase

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Page 5

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Read online

Page 5

I looked towards the house. The grass-green shutters covered the windows; a cream-andgreen striped awning flapped above the front door.

‘Well, so long,’ I said in a low voice to Kerman. ‘I’m going in now.’

‘Have a lovely time. Kerman’s voice was bitter from under the rug. ‘Don’t stint yourself. Have plenty of ice with your drinks.’

I walked along the terrace and screwed my thumb into the bell push. I could see through the glass panels of the door into a big hall and a dim, cool passage that led to the back of the house.

A tall, thin old man came down the passage and opened the front door. He looked me over in a kindly way. I had an idea he was pricing my suit and wishing he could buy me something a little better that wouldn’t disgrace the house. But I was probably wrong. He may not even have been thinking about me.

‘Mrs. Dedrick is expecting me.’

‘The name, sir?’

‘Malloy.’

He still stood squarely in the doorway.

‘Have you a card, please?’

"Well, yes, and I have a birthmark too. Remind me to show it to you one of these days.’

He tittered politely like an aged uncle out to have fun with his sister’s young hopeful.

‘So many gentlemen of the Press have tried to see Mrs. Dedrick. We have to take precautions, sir.’

I had an idea I would be standing there till next summer if I didn’t show him my card, so I got out my bill-fold and showed him my card: the non-business one.

He stood aside.

‘Would you wait in the lounge, sir?’

I went into the room where Souki had been shot. The Mexican rug had been cleaned. There were no bodies lying about this evening to welcome me; no untouched whisky and soda, no cigarette stub to spoil the repaired surface of the table.

‘If you could sneak me a double Scotch with a lot of ice in it, I’d appreciate it.’

‘Certainly, sir.’

He drifted across the room to the sideboard on which stood a bottle of Haig and Haig, glasses, a bucket of ice and White-rock.

I listened attentively as he moved, but I couldn’t hear his bones creak. I was surprised. He looked old enough for them to squeak. But, old as he was, he was no slouch when it came to mixing a drink. He handed me one strong enough to tip over a pony and trap.

‘If you would care to look at some periodicals while you wait, sir, I will get some for you.’

I lowered myself into an easy chair that accepted me as if it was doing me a favour, stretched out my legs and balanced my drink carefully on the arm of the chair.

‘You think there’ll be a long wait?’ I asked.

‘I have no experience in these matters, sir, but it would seem likely they won’t communicate with us until it is dark.’ He stood before me, not unlike one of the flamingoes I had seen in the lower garden, and every inch of him dedicated to a life of service. Probably he would never see seventy again, but the blue eyes were still alert and clear, and what he lacked in speed he made up in experienced efficiency: a family retainer straight out of Hollywood, almost too genuine to be true.

‘Yeah, I guess you’re right. Looks like a good three-hour wait: probably more.’ I dug out a package of cigarettes. He had a match flame ready before I got the cigarette into my mouth. ‘I didn’t get your name.’

The grizzled eyebrows lifted.

‘Wadlock, sir.’

‘Do you work for Mrs. Dedrick or Mr. Marshland?’

‘Oh, Mr. Marshland, sir. I have been lent to Mrs. Dedrick for the time being, and I am very happy to be of service to her.’

‘Have you been with the family long?’

He smiled benignly.

‘Fifty years, sir. I was with Mr. Marshland senior for twenty years, and I have been with Mr. Marshland junior for thirty years.’

That seemed to put us on a friendly footing, so I asked, ‘You met Mr. Dedrick when he was in New York?’

The benign expression went away like a fist when you open your fingers.

‘Oh, yes, sir. He stayed a few days with Mr. Marshland.’

‘I haven’t seen him. I’ve spoken to him on the ‘phone, and I’ve heard a lot about him, but there appears to be no photograph of him. What does he look like?’

I had an idea there was disapproval in the blue eyes now, but I wasn’t sure.

‘He is a well-built gentleman; dark, tall, athletic, with very good features. I don’t think I can describe him any better than that, sir.’

‘Did you like him?’

The bent old back stiffened.

‘Did you say you would like some periodicals, sir? You may find the wait a little tedious.’

I had my answer. Obviously for some reason or other this old man had as much use for Dedrick as I had for a punch on the jaw.

‘That’s all right. It makes a change to sit and do nothing.’

‘Very good, sir.’ He wasn’t friendly any more. ‘I will let you know when there is any news.’

He went away on his spindly old legs as dignified as an archbishop conferring a favour, and left me alone in a room full of bad memories. About a yard from my left foot Souki’s head had bled on the rug. Over by the fireplace stood the telephone into which Dedrick had breathed hurriedly and unevenly while he talked to me. I turned to stare at the casement window through which the kidnappers had probably come, gun in hand.

A short, dapper figure in a white tropical suit and a panama hat stood in the doorway, watching me. I hadn’t heard him arrive. I wasn’t expecting him. With my mind full of murder and thugs, he gave me a start that nearly took me to the ceiling.

‘I didn’t mean to startle you,’ he said in a mild, rather absent-minded way. ‘I didn’t know you were in here.’

While he was speaking he came into the room and put his Panama hat on the table. I guessed he would be Franklin Marshland, and looked to see if Serena took after him. She didn’t. He had a small, beaky nose, a heavy chin, dreamy, forgetful woman eyes and a full, rather feminine mouth. His wrinkled face was sun-tanned, and the thick fringe of glossy white hair, above which was a bald, sun-tanned patch, made him look like a clean-shaven and amiable Santa Claus.

I began to climb out of my chair, but he waved me to stay where I was.

‘Don’t move. I’ll join you in a whisky.’ He consulted a narrow, gold wrist-watch, worn on the inside of his wrist. ‘Quarter past six. I don’t believe in drinking spirits before six, do you?’

I said it was a good rule, but rules should be broken now and then if one was to preserve one’s sense of freedom.

He paid no attention to what I was saying. There was look of aloof disinterest on his face that hinted he seldom ever listened to anything anyone said to him.

‘You’re the chap who’s going to pay them the ransom money,’ he went on, stating a fact and not asking a question.

I said I was as he carried a fair-size snifter to an arm-chair opposite mine. He sat down and stared at me over the rim of the glass the way you would stare at some curious animal at the Zoo.

‘She tells me she’s going with you.’

‘So she says.’

‘I wish she wouldn’t, but nothing I say makes any difference. He sipped the whisky, stared down at his white buckskin shoe. He had the smallest male feet I have ever seen. ‘I never have been able to influence her one way or the other. A pity, really. Of course, old people are bores, but sometimes they are able to help the young if the young would only let them.’

I had the idea he was talking rather to himself than to me so I didn’t say anything.

He brooded off into a silence that lasted some time. I helped myself to another of my cigarettes, kept an intelligent expression on my face just in case he might think it worth while to speak to me and resisted the temptation to fidget.

In the middle distance I noticed the two Chinese gardeners had decided to call it a day. They had been staring at the umbrella standard for some time without touching it; now, having l

earned it by heart, they moved off to enjoy a well-earned rest.

‘Do you carry a gun?’ Marshland asked suddenly.

‘Yes; but I don’t expect to use it.’

‘I hope not. You’ll see she takes as little risk as possible, won’t you?’

‘Of course.’

He drank half the whisky. It didn’t do much to cheer him up.

‘These fellows have pretty big ideas. Five hundred thousand is an enormous sum of money.’

He seemed to expect me to say something so I said, ‘That’s why they snatched him. The risk is enormous too.’

‘I suppose it is. Do you think they’ll keep their side of the bargain?’

‘I don’t know. As I explained to Mrs. Dedrick, if he hasn’t seen them…’

‘Yes; she told me. You’re probably right I’ve been reading about some of the famous kidnapping cases of the past years. It would seem the higher the ransom the less likely is the chance of the victim surviving.’

I was suddenly aware that he wasn’t mild or absentminded any more, and that he was staring at me with an intent, rather odd expression in his eyes.

‘It depends on the kidnappers,’ I said, meeting his eyes.

‘I have a feeling we shan’t see him again.’ He got slowly to his feet, frowned round the room as if he had lost something. ‘Of course, I haven’t said anything to her about it, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they haven’t already killed him.’ The white eyebrows lifted. ‘What do you think?’

‘It’s possible.’

‘More than possible, perhaps?’

‘I’m afraid so.’

He nodded. The pleased, satisfied expression in his eyes jarred me to the heels.

He went out of the room, very spry and dapper, and humming a tune under his breath.

IV

It wasn’t until the hands of my watch had crawled round to eleven that the telephone bell rang. The five-hour wait had been interminable, and I was so het-up I very nearly answered the telephone myself, but someone in some other part of the house beat me to it.

I had been pacing up and down, sitting on the settee, staring tout of the window and chainsmoking during those five long hours. I had seen Wadlock for a few minutes when he had brought me dinner on a wheel wagon, but he hadn’t had anything to say and left me to serve myself.

I had been out just after eight o’clock to have a word with Kerman and to drop him a cold breast of chicken through the car window. I didn’t stay more than a minute or so. I was scared anyone who might be watching the house would hear his flow of bad language.

Now at last something was going to happen. Although Dedrick meant nothing to me, I was nervy after the long wait. I could imagine what Serena must be feeling like. She was probably fit to walk up a wall.

A few minutes later I heard movements outside and I walked into the hall.

Serena, in black slacks and a short, dark fur coat, came hurrying down the stairs, followed by Wadlock, who was carrying three oilskin-wrapped packages.

She looked white and ill; there was a pinched, drawn look about her that told more clearly than words how she had suffered during those long hours of waiting.

‘Monte Verde Mining Camp. Do you know it?’ she said in a low, unsteady voice.

‘Yes. It’s on San Diego Highway. It’ll take us about twenty minutes to get there if the traffic is light.’

Franklin Marshland appeared silently.

‘Where is it?’ he asked.

‘Monte Verde Mining Camp. It’s an old worked-out silver mine on San Diego Highway,’ I told him. ‘It’s a good spot for them.’ I looked at Serena’s white face. Her lips were trembling ‘Any news of your husband, Mrs. Dedrick?’

‘He—he is to be set free three hours after the money has be delivered. They will telephone us here where we will find him.

Marshland and I exchanged glances.

Serena caught hold of my arm.

‘Do you think they’re lying? If we let them have the money, we’ll have no hold on them at all.’

‘You haven’t a hold on them, anyway, Mrs. Dedrick. That’s what makes kidnapping such a filthy business. You’re entirely in their hands, and you just have to trust them.’

Wouldn’t it be better, my dear, if you let Mr. Malloy delivers the money, and you wait here for the second message?’ Marshland asked.

‘No!’

She didn’t look at him.

‘Serena, do be sensible. There’s always a chance they might be tempted to kidnap you. I’m sure Mr. Malloy is quite capable…’

She turned on him, distraught with misery and hysteria.

‘I’m going with him, and nothing you say will stop me!’ she cried wildly. ‘Oh, you needn’t pretend any more. I know you don’t want Lee to come out of this alive! I know you hate him! I know you’ve been gloating with joy that this has happened to him! But I’m bringing him back! Do you hear? I’m bringing him back!’

‘You’re being absurd…’ Marshland said, a faint flush coming to his face. His eyes looked hard and bitter.

She turned away from him to me.

‘Are you coming with me?’

‘Whenever you’re ready, Mrs. Dedrick.’

‘Then bring the money and come!’

She ran to the front door, jerked it open and went out on to the terrace.

Wadlock gave me the three packages.

‘You’ll take care of her, sir,’ he said.

I gave him a crooked grin.

‘You bet.’

Marshland walked away without looking at me.

‘She’s very upset, sir,’ Wadlock murmured. He looked upset himself.

I ran along the terrace, down the steps to the Cadillac.

‘I’ll drive,’ I said and tossed the packages into the back of the car. ‘I won’t be a moment. I want my gun.’

I left her getting into the Cad. and ran over to the Buick.

‘Monte Verde Mine,’ I said. ‘Give us five minutes, then come on—and watch out, Jack.’

A soft moan came from under the rug, but I didn’t wait. I went back to the Cadillac and climbed under the steering wheel. Serena sat huddled up in a corner. She was crying.

I sent the car shooting down the drive.

‘Don’t let it get you down.’

She went on crying quietly. I decided perhaps it was the best thing for her, and drove as fast as I could without taking risks, and ignored her.

As we drove along Orchid Boulevard I said, ‘Better get hold of yourself now. You haven’t told me yet what was said. If we make one false move, we may spoil his chance of getting back to you. These guys will be a lot more scared than we are. Now, come on, pull yourself together, and tell me. What did they say?’

It took her some minutes to control herself, and it wasn’t until we were shooting up Monte Verde Avenue that she told me.

The money is to be left on the roof of a shed standing before the old shaft. I don’t know if you know it?’

‘I know it. What else?’

‘Each parcel is to be placed at least a foot apart and in a row. After we have placed the parcels we must leave immediately.’

‘That the lot?’

She gave a little shiver.

‘Except for the usual threats about setting a trap.’

They didn’t bring your husband to the ‘phone?’

‘No. Why should they?’

‘Sometimes they do.’

The fact they hadn’t made it look bad for Dedrick, but I didn’t tell her so.

‘Was it the same man who spoke to you before?’

‘I think so.’

‘The same muffled voice?’

‘Yes.’

‘All right. Now this is what we do. I’ll stop the car at the entrance to the mine. You stay in the car. I’ll take the money and put it on the roof. You’ll be able to see every move I make. I’ll come straight back and get into the car. You will drive. At the beginning of Venture Avenue you’ll slow down and I’ll

drop off. You carry on and get back to the house.’

‘Why are you dropping off?’

‘I may catch sight of them.’

‘No!’ She caught hold of my arm. ‘Do you want them to kill him? We’re leaving the money and doing what they tell us. You’ve got to promise.’

‘Well, all right; it’s your money. If they double-cross you, you’ll stand no chance of catching up with them. I’ll guarantee they won’t see me.’

‘No!’ she repeated. ‘I’m not going to give them any opportunity to go back on the bargain.’

I swung the long black nose of the Cad into San Diego High-way.

‘All right, but it’s the wrong way to play it.’

She didn’t answer.

There was a lot of traffic belting along the Highway, and it took me some minutes before I could swing the car across to the dirt track leading to the mine. We went bumping over the uneven surface of the track. It was dark and forlorn up there, and the headlamps bounced off great clumps of scrub and dumps of rubbish. Although only a few hundred yards or so off the main Highway, once on this track it was as lonely and as dark as the inside of a tomb.

Ahead of me was the entrance to the mine. One of the high wooden gates had been blown off its hinges. The other still stood upright, but only just. I pulled up before the gateway. The headlights sent a long, searching beam along the cracked concrete driveway that led directly to the head of the shaft.

We could see the shed. It was not more than seven feet high; a rotten, derelict building where probably at one time the time-keeper had sheltered while he checked in the miners.

‘Well, that’s it. Now you wait here. If anything happens get out of the car and run for it.’

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

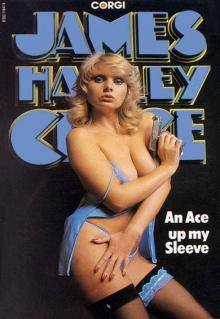

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

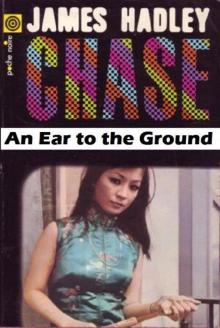

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

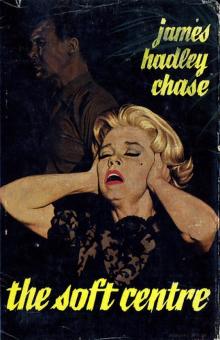

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

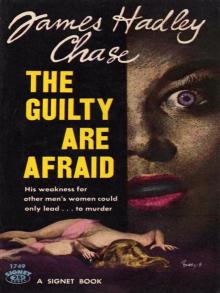

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

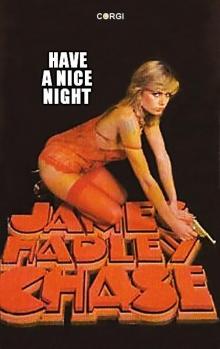

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

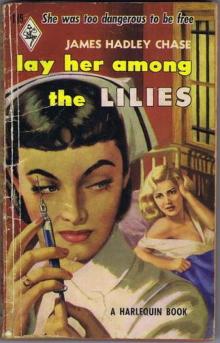

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

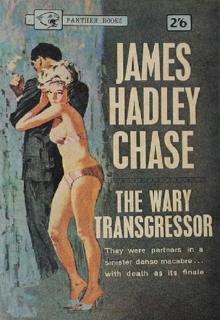

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

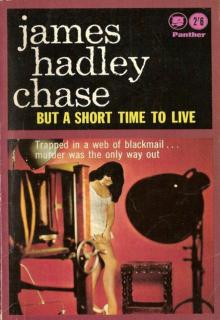

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

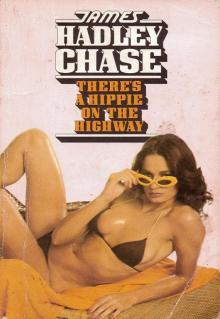

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

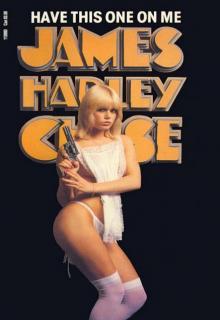

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail