- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf Page 4

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf Read online

Page 4

He had listened to Dr. Steed's report, humming under his breath, then he beamed at me.

"So we have a little trouble," he said. "Mr. Wallace, let me tell you I have heard of Colonel Parnell. I'm proud to meet one of his operators." He leaned forward and patted my arm. "A great agency. Great operators."

"Thank you," I said.

"A little mistake, huh?" He screwed up his pig-like eyes and released a soft belch. "No matter how smart you are, you can always make a little mistake. Right?"

"Sure," I said, my expression wooden.

He then looked at Dr. Steed.

"Now, Larry, you went up there and you tell me that poor old fella shot himself. . . right?"

"No doubt about it," Dr. Steed said, shaking his head mournfully. "I'm not surprised, Tim. The poor old fella lived in bad conditions, he had lost his grandson and he was lonely. You know, thinking about it, it's a merciful end. I don't stand in judgement of him. To be without legs, no one to take care of him . . . a merciful end."

"Yeah." Mason took off his Stetson hat, wiped his forehead, replaced the hat and also looked mournful. "So, there's no need to bring the State police into this sad affair?"

"Certainly not. A suicide doesn't necessitate consulting the State police," Dr. Steed said, his voice Mason beamed and rubbed his hands.

"That's good. I don't like those fellas. When's the inquest, Larry?"

"In a couple of days. I can clear this up quick. We'll have to bury him on the town, Tim. I don't think he had burial money. Still, we can afford it. I guess the town will want to put him away real good."

"You're right: the father of a national hero. You talk to them, Larry." Mason took out his wallet and produced a crumpled five-dollar bill. "I'd like to contribute. I'll leave it to you to raise the rest of the money. We must give him a good send-off."

Dr. Steed got to his feet as he put the bill in his pocket.

"I've always said, Tim, you have a generous heart. I'll be getting along. You leave the funeral arrangements to me." He turned to me. "Pleasure meeting you, Mr. Wallace. I'm sorry your visit to our little town has been so sad. Frederick Jackson was a fine man. His son was a fine man. We, in this little town, are proud of them both."

I stood and shook his hand, then watched him limp to the door. He paused, gave me a sly smile, then limped out into the hot sunshine.

"Well, now, Mr. Wallace," Mason said, beaming at me. "I expect you want to move along too. How about a little drink before we say goodbye?" He hoisted a bottle of Scotch out of his desk drawer.

"Not right now," I said, giving him the eye-ball-to-eye-ball treatment. "I'll be around for a day or so. You see, Sheriff, Jackson hired my agency to find his grandson. He paid us, so, although he is dead, he still remains our client."

Mason's eyes went glassy. He lost much of his sweaty happiness.

"No good wasting your time trying to locate the grandson. He could be anywhere. He left this district a good six years ago."

"We still have to try to find him, Sheriff," I said, continuing to stare at him. "Will you object if I ask around or do you want to have a word with Colonel Parnell? I understand you didn't inform the State police the boy has gone missing. Colonel Parnell might want to talk to them."

Mason winced as if he had bitten onto an aching tooth. He hoisted a glass from his desk and poured himself a big shot.

"I don't object, Mr. Wallace. You just go ahead, but you are sure wasting your time."

"I'm paid to waste my time," I said, then, without looking at Anderson, who was sitting as quiet as a well-behaved kitten, I walked out into the main street.

I decided, before making any further move, I must report to the Colonel. Aware the citizens of Searle were gaping curiously at me, I walked to where I had parked my car and drove fast to Paradise City.

One of the many things my father had taught me was to make a concise, verbal report: omitting no important fact, but cutting out the padding.

Colonel Parnell sat motionless in his executive chair, his eyes half closed, his big hands resting on the snowy blotter on his desk. He listened without interruption until I had told my story of my investigation up at Searle.

The clock on the colonel's desk showed 18.00. Usually, the colonel left the office sharp at 17.30. He was a golf addict and I was pleased my report had interested him enough for him to forget his evening round.

"That's the situation, sir, to-date." I concluded, only now realizing I had been talking non-stop for the past half hour. He looked directly at me.

"You made a good report, Dirk," he said. "Well now, Frederick Jackson still remains our client. We have been hired to find his grandson, but the fact that Jackson has been murdered could complicate the situation."

"The verdict will be suicide, sir," I said. "So no one can accuse us of being involved in a murder case."

He nodded, then picked up a pen and studied it thoughtfully, then again he looked at me.

"I'm wondering if I should pull you off this job and put Chick onto it. He has a lot more experience than you have. This might develop into a real mess."

I tried not to show my disappointment.

"That's up to you, sir."

He gave me a sudden grin.

"So far, you've handled this well, so I'm going to let you stay on the job, but if you run into trouble Chick will take over."

"Thank you, sir."

"Now let us see how the rest of this organization can help. Any ideas?"

"For one thing, I would like to be able to tell Bill Anderson that you are interested and could offer him a job. He is mad keen and this is important to me. I'll have to be careful how I nose around Searle: it is a hotbed of gossip, but Anderson, if sufficiently encouraged, could do some of my leg-work without stirring up the mud."

"Yes. You can tell him, as soon as a vacancy comes along, I will certainly give him an interview. If he has really been helpful, tell him he can count on a job with us."

"I'll tell him. Then I want to know what happened to Syd Watkins. I'm told he was discharged from the army, but after that he dropped out of sight. He hasn't been back to Searle. I think it’s important we get a trace on him."

"We'll check him out through the Army's records and the FBI if necessary and see what we come up with."

"I want to know if Mitch Jackson married, when and to whom."

"We should be able to dig into that."

"You told me, sir, that Jackson was the best soldier you had under your command. According to the gossip in Searle, he was no-good, vicious, dangerous and a thug."

Parnell frowned. His face hardened and he looked the Army veteran colonel that he was.

"That's nonsense! Mitch was my best staff. I never had complaints about his behaviour. I was told he was popular with his men. He had guts and great courage. No one wins the Medal of Honor without earning it!"

"Okay, sir. Maybe the citizens of Searle are prejudiced. Men can change."

"Yes. War changes men," Parnell said. "In my opinion, Mitch was a fine soldier."

I decided it would be wiser to keep my opinion of Mitch Jackson to myself. Maybe the citizens of Searle knew what they were saying and the colonel was the one who was prejudiced. A Staff sergeant who knew his way around could snow his commanding officer, but that was a fact I wasn't going to mention.

"That's all I can think of for the moment, sir," I said. "I'll return to Searle and put up at the local hotel. My job is to find the grandson, but if I get a lead to Jackson's murder I'll report to you."

"That's it, Dirk. Remember, we don't touch murder cases." He stared thoughtfully at me. "Until you get definite proof that Jackson was murdered, you keep digging."

"Yes, sir."

"You will be on an expense account. I'll talk to Glenda. I want the grandson found."

"Yes, sir."

He nodded, then got to his feet.

"I've missed a round of golf. You play golf, Dirk?"

"I used to, but it got too expensive."

&n

bsp; "What did you play to?"

"Well, on my best day, I've shot sixty-eight."

"You did?" He grinned. "We'll have a game together. That's some shooting."

I returned to my office to find Chick Barley clearing his desk.

"How's it going?" he asked. "Let's go and wet our tonsils."

At a near-by bar, I gave him the story I had given the colonel. He listened while he punished a bottle of Scotch.

"Nice going, Dirk. So you have a real job in your lap."

"It could be in your lap, Chick, if I don't get results."

Chick grinned. "You will. I'd hate to hell to get marooned in a dump like Searle."

"I'm bothered about Mitch Jackson. The colonel's nuts about him, but, from what I hear, Jackson was a real baddie. I'd like to check that out."

Chick regarded me with mild surprise.

"Let me tell you, Dirk, Mitch was the greatest. A guy who did what he did . . ."

"Look, let's skip the hero worship," I broke "Jackson may have been the white-headed hero to you officers, but I want to check him out by talking to the men who served under him. The rank-and-file. If they say he was the greatest, then he was the greatest. I've served in the army. I know a Staff sergeant can suck up to officers and be a brute to his men. It's odd to me that the general opinion of the citizens of Searle is they were glad to see the last of him. Okay, I admit war conditions change a man, but, from what I'm hearing, Jackson was a vicious thug. I want to check him out."

Chick poured himself another drink, then he nodded.

"I'll bet my last buck that Mitch was a real man, but you have a point. He was fine with us. Every order we gave him he carried out to perfection. We really could rely on him."

"Did you officers ever talk to the men to find out if they were as happy with Jackson as you were?"

"There was no need to. Damn it, we were a happy regiment. Mitch handled the men, we gave the orders, the whole thing worked."

"I want to check him out. I would like to talk to one of the men who served under him. Know anyone within reaching distance?"

Chick thought, then nodded. "Hank Smith, a coloured man. He has a job on the garbage-truck, Miami. I ran into him last year. I didn't remember him, but he remembered me. He insisted I go to his house in West Miami for a drink for old times. When he was in the regiment, he was a good soldier. Come to think of it, he wasn't out-going when I talked of Mitch and his medal. He just nodded, saying it was a fine thing for the regiment, then he changed the subject." Chick scratched his head. "Well, I don't know. You could have a point. I don't think the colonel would approve, but you could talk to Smith. You'll find him on West Avenue. He has a house at the corner, right."

An hour later, I edged my car into the coloured ghetto of West Miami. The time was 21.10. I had a hamburger with Chick, then he had gone off on a date, and after returning to my two-room apartment, packing a suitcase for my stay at Searle, I had decided to see if I could talk to Hank Smith.

It was a hot, steamy evening. West Avenue was lined, either side, with small, dilapidated houses.

Coloured people sat on their verandas, kids played in the street. I came under the searching stare of many eyes as I pulled up outside a shabby house on the corner, right.

A large, fat woman, her head enveloped in a bright red handkerchief, her floral dress fading from many washes, sat in a rocker, staring into space. Her small black eyes watched me as I got out of the car, pushed open the garden gate and walked up to the veranda. I was aware that some hundreds of eyes from the other verandas were also watching me.

"Mrs. Smith?" I asked, coming to rest before the woman. At close quarters, I could see she was around fifty years of age. Her broad, black face had that determined, strong face of a woman who is struggling to keep up a standard and refusing to accept the bitter fact that, for her, standards were slipping out of reach.

She gave me a curt, suspicious nod.

"That's me."

"Is Mr. Smith around?"

"What do you want with my husband? If you're selling something, mister, don't bother: I look after our money and I ain't got anything to spare."

A tall, massively built coloured man appeared in the doorway. He had on a clean white shirt and jeans. His close-cropped crinkly hair was shot with grey. His bloodshot black eyes were steady and, as he peeled his thick lips off strong white teeth in a wide smile, he looked amiable.

"You want something, mister?" he asked in a low rumbling voice.

"Mr. Smith?"

"Sure . . . that's me."

"Mr. Smith, I hope I'm not disturbing you. Chick Barley said you might be glad to meet me."

His smile widened.

"Mr. Barley is a great man. Sure, I'm always pleased to meet any friend of Mr. Barley." He came forward and offered is his hand which I shook.

"Dirk Wallace," I said. "I work for Colonel Parnell."

He smiled again.

"Another great man. Well, come on in, Mr. Wallace. Our neighbours are kind of nosey. Let's have a drink."

"Hank!" his wife said sharply. "Watch with the drink!"

"Relax, Hannah," he said, smiling affectionately at the woman. "A little drink does no harm to good friends."

He led me into a small living-room. The furniture was austere but reasonably comfortable. There were two armchairs, a deal table and three upright chairs.

"Sit you down, Mr. Wallace," Smith waving to one of the armchairs. "How about a little Scotch?"

"That would be fine," I said.

While he was away, I looked around. There were photographs of him in uniform, his wedding photograph and photographs of two bright-looking kids. He returned with two glasses, clinking with ice and heavy with Scotch.

"And how is Mr. Barley?" he asked, giving me one of the glasses. "I haven't seen him for some time."

"He's fine," I said, "and he sends you his best." Smith beamed and sat down.

"You know, Mr. Wallace, we soldiers never had any time for MPs, but Mr. Barley was different. Many a time, he'd look the other way when we were in the front line. The guys really liked him."

He raised his glass and saluted me. We drank. The Scotch nearly ripped the skin off my tonsils.

He eyed me.

"A bit strong, huh?" he asked, seeing my eyes water. "We old soldiers like our liquor with a big kick."

I put the glass on the table.

"That's a fact." I managed to grin. "I never did get to 'Nam. It was over before my lot finished training."

"Then I guess you were lucky. Nam was no picnic."

I took out my pack of cigarettes and offered it. We both lit up.

"Mr. Smith . . .?"

His smile widened.

"You call me Hank, Mr. Wallace. I guess you were an officer . . . right?"

"That's old history. Call me Dirk."

"Fine with me." He drank, sighed, then said, "You working for the colonel?"

"Yes. Hank, I've come to see you because Chick said you could help."

"Is that right?" He showed surprise. "Well, sure. Help? What's that mean?"

"Mitch Jackson. Remember him?"

Hank lost his smile.

"I remember him," he said, his voice suddenly cold and flat.

"I'm digging into his past, Hank. It's important. Whatever you say is in confidence. I just want to have your truthful opinion of him."

"Why should you want that?"

"His father died yesterday. There's an investigation. We think Mitch Jackson could be remotely hooked to his father's death."

"You want my truthful opinion?"

"Yes. I assure you if you have anything to tell me it goes no further than these four walls. You have my word."

He moved his big feet while he thought.

"I don't believe in speaking ill of the dead," he said finally. "Especially a Medal of Honor hero."

I sampled the Scotch again. It was still dreadful, but I found I was getting used to its kick.

"How did the men react to Mit

ch? How did you react?"

He hesitated, then shrugged

"He had a lot of favourites. That was the trouble. Maybe you don't know, but, when a Staff sergeant has favourites and runs the rest of the men into the ground, he ain't popular. That's what Jackson did. To some he was like a father. To others he was a real sonofabitch."

"How was he with you?"

"I had a real bad time with him: any dirty job, I got it, but it wasn't only me. More than half the battalion got the shitty end of the stick and the other half had it good."

"There must have been a reason."

"There was a reason all right. All those kids who went into that jungle before the bombers arrived were his favourites. That, and no other reason, made him drive after them. Not because he loved them. But because they were worth more than a thousand bucks a week to him, and he was so goddamn greedy he couldn't stand to ice his pay-roll being killed. If those kids had been his non-favourites, he wouldn't have moved an inch. That's how he won his medal: trying to save his weekly pay-roll."

"I don't get it, Hank. Why should those kids pay him a thousand bucks a week?"

Hank finished his drink while he eyes me.

"This is strictly off the record? I don't want to get involved in any mess."

"Strictly off the record."

"Mitch Jackson was a drug-pusher."

It was common knowledge that the Army, fighting in Vietnam, had a high percentage of drug-addicts, and a lot of youngsters were on reefers. All the same this was something I hadn't expected to "That's a serious accusation. Hank," I said. "If you knew, why didn't you report to Colonel Parnell?"

He gave a sour smile.

"Because I wanted to stay alive. I wasn't the only one who knew, but no report was made. I'll tell you something. A sergeant, working under Jackson, found out what Jackson was up to. Pie told Jackson to pack it in or he'd put in a report. The sergeant and Jackson went out together on a patrol. The sergeant didn't come back. Jackson reported he had been killed by a 'Nam sniper. A couple of kids, when Jackson propositioned them to buy his junk, refused. They also died by snipers' bullets, so the word got around to keep the mouth shut. Anyway, what good would I've done? I'd only have landed myself in trouble. A coloured man reporting a favourite Staff sergeant to a man like Colonel Parnell who thought Jackson was the tops? So I kept my mouth shut."

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

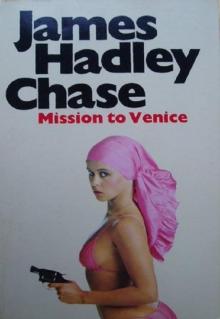

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

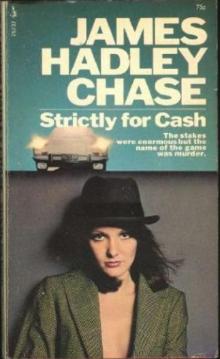

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

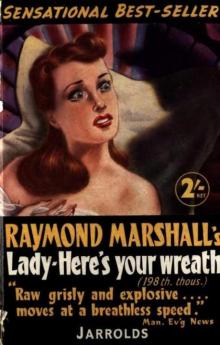

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

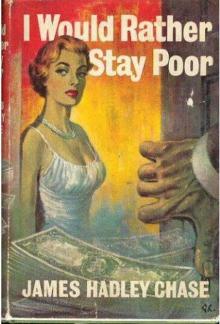

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail