- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1950 - Mallory Page 2

1950 - Mallory Read online

Page 2

She was quick to catch the sharpness in his voice.

‘But you need your money. It doesn’t matter. Honest, I don’t mind. It’s kind of you.’

‘Now, stop it, Effie,’ he said, and was suddenly glad he had made the promise. It was time he did something for her. He couldn’t expect to have her prayers for nothing. ‘Come on. Take me upstairs. We’ll talk about it some other time.’

She was glad to escape from his half-jeering smile and ran up the stairs. He followed her more slowly, thinking, ‘I’m getting soft. It’s time I did a job of work. But I’ll do it. She’s worth it in her funny way.’

He caught up with her on the top landing.

‘In here,’ she said, and opened a door.

He entered a small, dark room and stumbled against a bed.

‘Don’t put on a light,’ he said quickly, sensing that was what she was about to do. ‘There’s someone out there I want to see.’

‘Who is it?’ she asked, joining him at the window.

‘That’s what I want to find out.’ He could see the mouth of the cul-de-sac and part of Frith Street. A street light lit up the shadows, but there was no one in sight. He stood for some minutes peering down into the semi-darkness. ‘They’re there somewhere,’ he muttered to himself, then pushed up the window, and leaned out, feeling the rain cold against his face. Below was a sloping roof.

‘What are you doing?’ Effie asked nervously as he slid his leg over the sill.

‘I’m going to get a better look.’

‘But you’ll fall!’ She caught hold of his arm. ‘You mustn’t. You’ll fall!’

‘Of course I won’t,’ he said, controlling his impatience, and pulling free. ‘It’s all right, Effie. I’m used to this kind of thing.’

‘But you will... please don’t...’

‘Don’t fuss,’ he said sharply, and holding on to the sill with one hand, allowed his body to slide down the wet tiles until his feet reached the gutter.

From where she stood, safe and out of the rain, his position looked perilous, and unable to watch him, she turned away, hiding her face in her hands. It gave him an odd feeling of elation to see how much she cared for him.

The tiles were wet and greasy. If he slipped or if the gutter gave under his weight he would pitch head first into the cul-de-sac. But he wasn’t thinking of sudden death; it didn’t occur to him that he might slip. He made for the brick projection that separated the Amethyst Club from the adjacent building. From there, he guessed he would have an uninterrupted view of the whole of Frith Street.

The cold drizzle, falling now in a fine cloud, ran off the roof in rivulets. Once the gutter bent under his weight and he swore softly, but he reached the projection, gripped the stack pipe and hauled himself up so he could peer cautiously into the street below. As he had guessed he now had a clear view of the street, and began methodically to examine every dark doorway and passage, watching for a betraying movement or a shouldering cigarette end that Would give away the hiding place of the man he was looking for.

He remained motionless for some time, unaware of the cold and wet, but he saw nothing to attract his attention. Still he waited, obstinate and angry, his legs becoming cramped and his fingers stiffening on the cold stack pipe, his eyes never ceased their searching patrol of the street. Finally his patience was rewarded for he spotted a movement in a dark doorway some seventy yards or so from the mouth of the cul-de-sac. His eyes had grown accustomed to the darkness by now, and he could just make out a dim figure standing in the doorway.

At this moment a taxi passed and its headlight swept the doorway. Corridon had a brief glimpse of a short, thickset man in a shabby olive-green trench coat that was buttoned up to his chin and a black military beret pulled down over his dome-like head. Then darkness again closed down as the taxi went on, turning the corner into Old Compton Street.

Corridon had no doubt that this man was one of those who had been following him for the past twenty-four hours. He had never seen him before, had no idea who he was, could think of no reason why he should be waiting in the cold and wet to follow him as soon as he left the club. And Corridon was sure there were others. It seemed probable that the foreign-looking girl whom Crew had brought to the club was another of them.

As Corridon began to work his way back along the gutter towards Effie’s room he decided not to bother with the man in the black beret. Crew would know all about it. Zani could tell him where Crew was to be found. He’d find out from Crew.

chapter two

I

On the following morning, a few minutes after ten o’clock, Corridon arrived at Crew’s flat.

Corridon had spent the night at the Amethyst Club, dozing in a chair, his feet on the table, ignoring Zani’s growling insistence that he should go home. At daybreak he had again climbed to the projection on the roof but saw no sign of the man in the black beret. Taking no risks, he had left the club by climbing a wall at the back of the building to an alley that led eventually into Dean Street. From there he took a taxi to Charing Cross Road where he had a shave and breakfast at a nearby cafe. He took his time over his breakfast, drank several cups of coffee, read the newspaper and smoked innumerable cigarettes.

He sat at a table by the muslin-covered window and watched continually for the man in the black beret, but he didn’t see him. When he finally left the cafe he wandered around the back streets of the West End for an hour or so until he was sure no one was following him, then he set off to see Crew.

Crew had a four-room flat over a tobacconist’s shop in a dirty little street off Drury Lane. To reach the flat you had to pass two smelly dustbins that blocked the entrance to a flight of uncarpeted stairs leading to a dimly lit landing. At the far end of the landing was Crew’s front door.

To see Crew moving purposely about the West End you might have mistaken him for a member of the Diplomatic Service or even perhaps a Harley Street specialist - specializing, of course, in women’s diseases. There was an air of distinction and authority about him; a bedside manner that deceived people into thinking he was a man of substance, culture and importance.

It irked Crew to have to live in such a sordid district, but it was essential for him to be near the West End at a reasonable rent, and this little flat was the best he could afford. For he was by no means a man of substance. Although always well dressed, his aristocratic appearance and his nimble fingers were his only assets. By profession - if you could call it a profession - he was a pickpocket; a secret he shared with no one, and of which he was slightly ashamed. Even Corridon, whose knowledge of the West End and the activities of its underworld members was encyclopaedic, had no idea what he did.

Crew had been picking pockets for years. He had a horror of the police and of being arrested, and selected his victims with the utmost care, making sure that what he got from them always justified the risk he ran. His fingers were incredibly nimble. He could steal a watch off a wrist, a wallet protected by an overcoat and a pair of links out of shirt cuffs without his victim being aware of what was happening. To remove a necklace or brooch, to open a handbag on a woman’s arm and take the money in it was child’s play to him. No one suspected him; least of all the police who were well aware that a brilliant pickpocket was working the West End, and had been trying to trap him for years.

By the time Corridon reached Crew’s flat, the rain had given place to thin, watery sunshine that emphasized the dirt and decay of the houses lining the street. He was surprised that Crew should live in such a district, remembering him from the past, freshly shaved, well dressed, fastidious in his appearance, and he paused outside the tobacconist’s shop, wondering if Zani had given the correct address. No one paid him any attention. A long line of cars and trucks were parked along the kerb, and men carrying boxes of flowers piled high on their heads jostled him as they loaded their vehicles.

Zani had said the flat was over a tobacconist’s shop and this was the only tobacconist’s shop in the street. Dodging a driver w

ho bore down on him with a sack of potatoes on his back, Corridon mounted the uncarpeted stairs, moving silently on crepe-soled shoes. He paused at the top of the stairs to listen, but the street was alive with noises as lorries manoeuvred to pass the line of trucks and cars, and drivers shouted to each other as they drove up on the pavement, reversing and roaring their engines, blanketing all other sounds. Walking softly to Crew’s front door, Corridon rapped sharply and put his ear against the door panel and listened. There was a long pause, then he heard a movement on the other side of the door, then a bolt slid back and the door eased open. Crew appeared.

Although Corridon hadn’t seen him for four years he recognized Crew immediately. Time had dealt lightly with him. He had perhaps grown a little thinner and his hair had receded slightly from his high forehead. There were lines now running from his nose to his mouth and a network of faint wrinkles under his eyes, but otherwise he was the same immaculate, distinguished-looking Crew whom Corridon had once hit over the head with a beer bottle.

When Crew saw Corridon he gave a convulsive start and sprang back, trying to slam the door, but Corridon’s foot was in the way.

‘Hello, Crew,’ Corridon said gently. ‘Weren’t you expecting me?’

Crew peered round the door, leaning his weight against it, imprisoning Corridon’s foot. He breathed heavily, his mouth hanging open, a vacant look of fear in his eyes.

‘You can’t come in,’ he said in a shaky, breathless voice. ‘Not now. It’s inconvenient.’

Corridon smiled jeeringly and put his hand on the door and gave it a sudden hard shove, sending Crew staggering back. He had entered the little hall and closed the door.

‘Remember me?’ he asked, and looked pointedly at the jagged white scar that ran across Crew’s forehead and disappeared into the thinning fair hair.

‘It’s Corridon, isn’t it?’ Crew said, backing away. ‘You can’t come in. I was just going out.’ His smile flickered on and off like an electric light with a faulty connection. ‘I’m sorry, but I’m late as it is.’ He looked into the deepset, cold grey eyes and began to wring his hands, then suddenly conscious of what he was doing, hurriedly thrust them into his trouser pockets. ‘I – I shall have to turn you out. Perhaps some other time, old boy.’

He grimaced at Corridon, trying to appear at ease, but succeeding only in showing an abject fear.

Corridon glanced round the hall. A vase of Keizer Kroom tulips on a table, their red and yellow petals a little full-blown, surprised him. He hadn’t imagined flowers and Crew going together.

‘I see you’ve still got that scar,’ he said and pointed. ‘There’s a reasonable chance you’ll get another.’

Crew backed against the wall. He looked at Corridon in horror.

‘What do you want?’ He stopped trying to smile, and his air of authority and importance fell from him, leaving only his effeminacy and sham.

‘Are you alone?’ Corridon asked.

‘Yes . . . but you’d better not touch me.’ Little beads of perspiration gathered at Crew’s temples. ‘My solicitor . . .’ He broke off, realizing the futility of talking of solicitors to a man like Corridon. He repeated weakly, ‘You’d better not touch me . . .’

‘Go in there,’ Corridon said, pointing to a door. ‘I want to talk to you.’

Crew went into the room. He walked slowly, his legs dragging. Corridon followed him, closed the door and surveyed the room with raised eyebrows. It wasn’t the kind of room he expected Crew to live in. It was restful and pleasant; painstakingly furnished to give comfort and tranquillity, and it achieved its purpose. Wherever he looked there were vases of tulips and narcissi, filling the room with their sweet, cloying scent.

‘You know how to make yourself comfortable, don’t you?’ he said as he sat on the arm of a big, easy chair. ‘Very pretty, and flowers too. Yes, very pretty indeed.’

Crew hung on to the back of the settee. He looked as if he were going to faint.

Corridon studied him. He couldn’t understand why Crew was so frightened. He wasn’t the type who scared easily. Corridon remembered his bland manner when he had caught him cheating. It had been his smug confidence, making a joke of it, that had incited Corridon to hit him.

‘What’s the matter with you?’ he demanded sharply. What’s scaring you?’

Crew made a gulping noise in his throat. He muttered something, moved uneasily from one foot to the other, finally managed to say, ‘Nothing... nothing’s the matter.’

‘Well, you’re certainly acting as if you were scared,’ Corridon said, watching him. ‘But if there’s nothing - there’s nothing.’ He suddenly barked: ‘Who’s Jeanne?’

Silence hung in the room, broken only by the sharp busy tick of the clock on the mantel and the sudden uneasy rasp of Crew’s breathing.

‘I asked you who Jeanne is - the girl you took to the Amethyst Club three nights ago,’ Corridon said through the silence.

Crew’s mouth worked convulsively. He said: ‘Go away. If you don’t leave me alone I’ll call the police.’

‘Don’t be a fool.’ Corridon took out a packet of cigarettes, lit one and tossed the match into the hearth. ‘You took this girl to the club and she asked Max about me. I’m interested. Who is she?’

‘That’s a lie,’ Crew said in a whisper. ‘She doesn’t even know you. She’s never seen you.’ His finger hooked into his collar and he pulled at the collar as if it were strangling him. ‘Why should she ask Max about you? It’s a lie.’

‘All right, it’s a lie. But who is she?’

Crew hesitated. He puzzled Corridon. He could see Crew was frightened, but it was beginning to dawn on him that Crew wasn’t frightened of him. He had been frightened before Corridon had knocked on the door.

‘No one you know,’ Crew said sullenly. ‘A friend. What’s it to you who she is?’

Corridon blew a smoke ring and stabbed at it with his finger.

‘Do you want me to hit you?’ he asked, his expression polite and interested. He watched the smoke ring dissolve, added. ‘I will if you don’t talk.’

Crew stiffened. He was expecting this. He had a horror of violence, and already he could feel Corridon’s massive fist smash into his face. He remained still, his eyes darting this way and that, tense as if trying to make up his mind what to do. Then he glanced over his shoulder to another door at the far end of the room. He looked from the door to Corridon as if he were trying to convey a message.

‘You’d better not touch me,’ he said, his mouth twitching.

Again he looked at the door.

Was he trying to tell him they weren’t alone in the flat?

Corridon wondered. He too looked from Crew to the door and back and raised his eyebrows inquiringly. Crew nodded eagerly, like a man in a foreign country who has at last succeeded in making himself understood by gestures. He put his finger to his lips, reminding Corridon of a third-rate actor in a melodrama, and Corridon felt an inclination to laugh.

‘Tell me about Jeanne,’ he said, getting quietly to his feet.

‘There’s nothing to tell.’ Again the frightened eyes strayed to the door. ‘She’s just a girl I know.’

Corridon moved silently up to Crew.

‘Who’s in there?’ he whispered, his face close to Crew’s. He could see the tiny sweat beads on Crew’s face and smelt the brilliantine on his hair. Aloud, he went on, ‘What does she do? Where does she come from?’

Grew raised three fingers and motioned to the door.

‘I don’t know anything about her. She was a pickup.’ He tried desperately to be jaunty. The flickering smile came and went. ‘You know how it is. She was a pretty little thing. I haven’t seen her since.’

‘Three of them?’ Corridon whispered.

Crew nodded. He was recovering slightly. Returning confidence crept over him like a second skin.

Raising his voice, Corridon asked, ‘Do you know a little fella in a black beret?’

The returning colour and confidenc

e drained out of Crew’s face. He sagged at the knees. It was as if Corridon had hit him suddenly and viciously in the belly.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he gasped, then screwing himself into a frenzy of courage, shouted: ‘Get out! I’ve had enough of this. You’ve no right to force your way in here. Get out! I won’t have you here!’

Corridon laughed at him.

‘Your pals must be pretty sick of you by now,’ he said contemptuously, then raising his voice, he called, ‘Come on out, the three of you. He’s told me you’re in there.’

Crew gave a gasp and slumped into a chair. He seemed to stop breathing in the pause that followed, then as the door of the far room opened he drew a quick intake of breath that whistled through his teeth. The man in the black beret came quietly into the room, a Mauser pistol in his gloved hand.

II

Several times during his life Corridon had been held up by a gun. It was an experience that made him nervous and angry. It made him nervous because he knew how easily any fool could let off a gun; whether they meant to or not. There were people who held you up with a gun who didn’t mean to shoot, and there were people who held you up with a gun who did. Corridon decided that the man in the black beret would shoot if he were given the slightest opportunity. Corridon could tell this by looking into his dark protruding eyes. Life, to this little man, was of no more importance than the dirt on his shabby trenchcoat or that grimed the finger curling round the trigger.

The big Mauser pistol wasn’t a threat: it was harnessed death to be released without pity by the squeezing of a finger against metal.

‘Keep very still, my friend,’ the man in the black beret said.

His accent was scarcely perceptible, but it was there, and Corridon recognized it. He was a Pole. ‘No tricks, please or you will be sorry.’ The gun-sight centred on Corridon’s chest.

Corridon looked beyond the threatening gun to the door.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

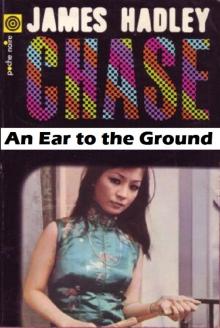

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

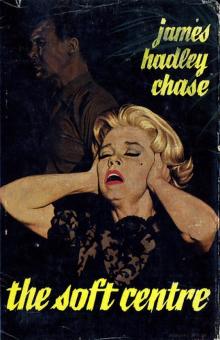

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

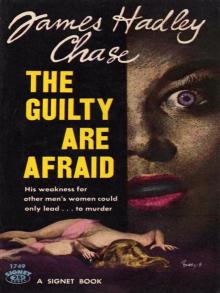

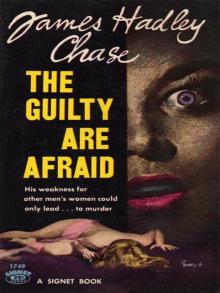

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

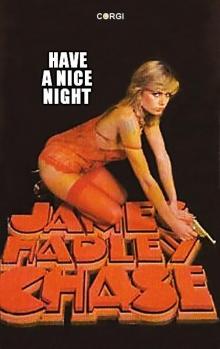

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

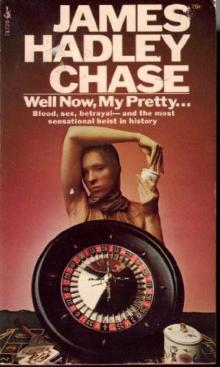

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

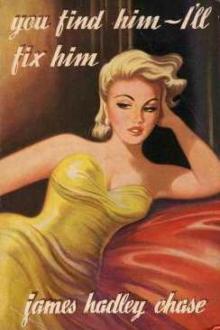

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

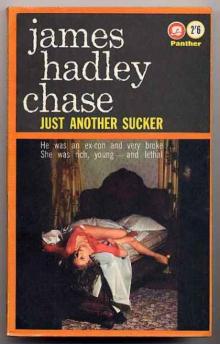

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

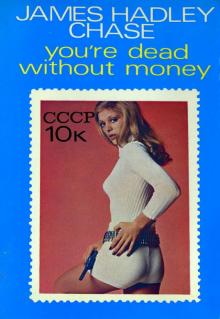

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

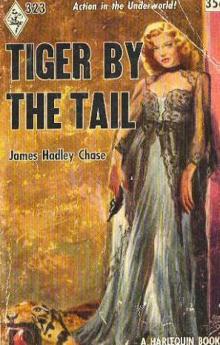

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail