- Home

- James Hadley Chase

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Page 2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Read online

Page 2

“Anyone at home?” I asked, searching for a cigarette and lighting it when I found one. It took all that time before he worked up enough strength to say: “Don’t bother me, Jack. I’m busy.”

“I can see that,” I said, blowing smoke at him. “I’d love to sneak up on you when you’re relaxing.”

He spat accurately at a tub of last summer’s pelargoniums from which no one had bothered to take cuttings, and went on with his whittling. As far as he was concerned I was now just part of the uncared-for landscape.

I didn’t think I would get anything useful out of him, and besides, it was too hot to bother, so I went on to the house, climbed the broad steps and leaned my weight on the bell-push.

A funereal hush hung over the house. I had to wait a long time before anyone answered my ring. I didn’t mind waiting. I was now in the shade, and the drowsy, next-year-will-do atmosphere of the place had a kind of hypnotic influence on me. If I had stayed there much longer I would have begun whittling wood myself.

The door opened, and what might have passed for a butler looked me over the way you look someone over who’s wakened you up from a nice quiet nap. He was a tall, lean bird, lantern-jawed, grey-haired, with close-set, yellowish eyes. He wore one of those waspcoloured vests and black trousers that looked as if he had slept in them, and probably had, no coat, and his shirt sleeves suggested they wanted to go to the laundry, but just couldn’t be bothered.

“Yes?” he said distantly, and raised his eyebrows.

“Miss Crosby.”

I noticed he was holding a lighted cigarette, half-concealed in his cupped hand.

“Miss Crosby doesn’t receive now,” he said, and began to close the door.

“I’m an old friend. She’ll see me,” I said, and shifted my foot forward to jam the door.

“The name’s Malloy. Tell her and watch her reaction. It’s my bet she’ll bring out the champagne.”

“Miss Crosby is not well,” he said in a flat voice, as if he were reading a ham part in a hammier play. “She doesn’t receive any more.”

“Like Miss Otis?”

That one went past him without stirring the air.

“I will tell her you have called.” The door was closing. He didn’t notice my foot. It startled him when he found the door wouldn’t shut.

“Who’s looking after her?” I asked, smiling at him.

A bewildered expression came into his eyes. For him life had been so quiet and gentle for so long he wasn’t in training to cope with anything out of the way.

“Nurse Gurney.”

“Then I’d like to see Nurse Gurney,” I told him, and leaned some of my weight on the door.

No exercise, too much sleep, cigarettes and the run of the cellar had sapped whatever iron he had had in his muscles. He gave way before my pressure like a sapling tree before a bulldozer.

I found myself in an over-large hall, facing a broad flight of stairs which led in a wide, half-circular sweep to the upper rooms. On the stairs, halfway up, was a white-clad figure: a nurse.

“All right, Benskin,” she said. “I’ll see to it.”

The tall, lean bird seemed relieved to go. He gave me a brief, puzzled stare, and then cat-footed across the hall, along a passage and through a baize-covered door.

The nurse came slowly down the stairs as if she knew she was good to look at, and liked you to look at her. I was looking all right. She was a nurse right out of a musical comedy; the kind of nurse who sends your temperature chart haywire every time you see her. A blonde, her lips scarlet, her eyes blue-shaded: a very nifty number: a symphony of curves and sensuality; as exciting and as alive and as hot as the flame of an acetylene torch. If ever she had to nurse me I would be bed-ridden for the rest of my days.

By now she was within reaching distance, and I had to make a conscious effort not to reach. I could tell by the expression in her eyes that she was aware of the impression she was making on me, and I had an idea I interested her as much as she interested me. A long, tapering finger pushed up a stray curl under the nurse’s cap. A carefully plucked eyebrow climbed an inch. The red painted mouth curved into a smile. Behind the mascara the green-blue eyes were alert and hopeful.

“I was hoping to see Miss Crosby,” I said. “I hear she’s not well.”

“She isn’t. I’m afraid she isn’t even well enough to receive visitors.” She had a deep, contralto voice that vibrated my vertebrae.

“That’s too bad,” I said, and took a swift look at her legs. Betty Grable’s might have been better, but there couldn’t have been much in it. “I’ve only just hit town. I’m an old friend of hers. I had no idea she was ill.”

“She hasn’t been well for some months.”

I had the impression that as a topic of conversation Maureen Crosby’s illness wasn’t Nurse Gurney’s idea of fun. It was just an impression. I could have been wrong, but I didn’t think so.

“Nothing serious, I hope?”

“Well, not serious. She needs plenty of rest and quiet.”

If she had had any encouragement this would have been her cue for a yawn.

“Well, it’s quiet enough here,” I said, and smiled. “Quiet for you, too, I guess?”

That was all she needed. You could see her getting ready to unpin her hair.

“Quiet? I’d as soon be buried in Tutankhamen’s tomb,” she exclaimed, and then remembering she was supposed to be a nurse in the best Florence Nightingale tradition, had the grace to blush. “But I guess I shouldn’t have said that, should I? It isn’t very refined.”

“You don’t have to be refined with mc,” I assured her. “I’m just an easygoing guy who goes even better on a double Scotch and water.”

“Well, that’s nice.” Her eyes asked a question, and mine gave her the answer. She giggled suddenly. “If you have nothing better to do…”

“As an old pal of mine says, ‘What is there better to do?’”

The plucked eyebrow lifted.

“I think I could tell him if he really wanted to know.”

“You tell me instead.”

“I might, one of these days. If you would really like a drink, come on in. I know where the Scotch is hidden.”

I followed her into a large room which led off the hall. She rolled a little with each step, and had weight and control in her hips. They moved under the prim-looking white dress the way a baseball flighted with finger-spin moves. I could have walked behind her all day watching that action.

“Sit down,” she said, waving to an eight-foot settee. “I’ll fix you a drink.”

“Fine,” I said, lowering myself down on the cushion-covered springs. “But on one condition. I never drink alone. I’m very particular about that.”

“So am I,” she said.

I watched her locate a bottle of Johnny Walker, two pint tumblers and a bottle of Whiterock from the recess in a Jacobean Court cupboard.

“We could have ice, but it’ll mean asking Benskin, and I guess we can do without Benskin right now, don’t you?” she said, looking at me from under eyelashes that were like a row of spiked railings.

“Never mind the ice,” I said, “and be careful of the Whiterock. That stuff can ruin good whisky.”

She poured three inches of Scotch into both glasses and added a teaspoonful of Whiterock to each.

“That look about right to you?”

“That looks fine,” I said, reaching out a willing hand. “Maybe I’d better introduce myself.

I’m Vic Malloy. Just plain Vic to my friends, and all good-looking blondes are my friends.”

She sat down, not bothering to adjust her skirts. She had nice knees.

“You’re the first caller we have had in five months,” she said. “I was beginning to think there was a jinx on this place.”

“From the look of it, there is. Straighten me out on this, will you? The last time I was here it was an estate, not a blueprint for a wilderness. Doesn’t anyone do any work around here any more?”

“You know how it is. Nobody cares.”

“Just how bad is Maureen?”

She pouted.

“Look, can’t we talk about something else? I’m so very tired of Maureen.”

“She’s not my ball of fire either,” I said, tasting the whisky. It was strong enough to raise blisters on the hide of a buffalo. “But I knew her in the old days, and I’m curious. What exactly’s the matter with her?”

She leaned back her blonde head and lowered most of the Scotch down her creamy-white, rather beautiful throat. The way she swallowed that raw whisky told me she had a talent for drinking.

“I shouldn’t tell you,” she said, and smiled. “But if you promise not to say a word…”

“Not a word.”

“She’s being tapered off a drug jag. That’s strictly confidential.”

“Bad?”

She shrugged.

“Bad enough.”

“And in the meantime when the cat’s in bed the mice’ll play, huh?”

“That’s about right. No one ever comes near the place. She’s likely to be some time before she gets around again. While she’s climbing walls and screaming her head off, the staff relaxes. That’s fair enough, isn’t it?”

“Certainly is, and they certainly can relax.”

She finished her drink.

“Now, let’s get away from Maureen. I have enough of her nights without you talking about her.”

“You on night duty? That’s a shame.”

“Why?” The green-blue eyes alerted.

“I thought it might be fun to take you out one night and show you things.”

“What things?”

“For a start I have a lovely set of etchings.”

She giggled.

“If there’s one thing I like better than one etching it’s a set of etchings.” She got up and moved over to the whisky bottle. The way her hips rolled kept me pointing like a gun-dog.

“Let me freshen that,” she went on. “You’re not drinking.”

“It’s fresh enough. I’m beginning to get the idea there are things better to do besides drinking.”

“Are you? I thought perhaps you might.” She shot more liquor into her glass. She didn’t bother with the Whiterock this time.

“Who looks after Maureen during the day?” I asked as she made her way back to the settee.

“Nurse Fleming. You wouldn’t like her. She’s a man-hater.”

“She is?” She sat beside me, hip against hip. “Can she hear us?”

“It wouldn’t matter if she did, but she can’t. She’s in the left wing, overlooking the garages. They put Maureen there when she started to yell.”

That was exactly what I wanted to know.

“To hell with all man-haters,” I said, sliding my arm along the back of the settee behind her head. She leaned towards me. “Are you a man-hater?”

“It depends on the man.” Her face was close to mine so I let my lips rest against her temple.

She seemed to like that.

“How’s this man for a start?”

“Pretty nice.”

I took the glass of whisky out of her hand and put it on the floor.

“That’ll be in my way.”

“It’s a pity to waste it.”

“You’ll need it before long.”

“Will I?”

She came against me, her mouth on mine. We stayed like that for some time. Then suddenly she pushed away from me and stood up. For a moment I thought she was just a kiss-and-good-bye girl, but I was wrong. She crossed the room to the door and turned the key.

Then she came back and sat down again.

III

I parked the Buick outside the County Buildings at the corner of Feldman and Centre Avenue, and went up the steps and into a world of printed forms, silent passages and old-young clerks waiting hopefully for deadmen’s shoes.

The Births and Deaths Registry was on the first floor. I filled in a form and pushed it through the bars to the redheaded clerk who stamped it, took my money and waved an airy hand towards the rows of files.

“Help yourself, Mr. Malloy,” he said. “Sixth file from the right.”

I thanked him.

“How’s business?” he asked, and leaned on the counter, ready to waste his time and mine.

“Haven’t seen you around in months.”

“Nor you have,” I said. “Business is fine. How’s yours? Are they still dying?”

“And being born. One cancels out the other.”

“So it does.”

I hadn’t anything else for him. I was tired. My little session with Nurse Gurney had exhausted me. I went over to the files. C file felt like a ton weight, and it was all I could do to heave it on to the flat-topped desk. That was Nurse Gurney’s fault, too. I pawed over the pages, and, after a while, came upon Janet Crosby’s death certificate. I took out an old envelope and a pencil. She had died of malignant endocarditis, whatever that meant, on 15th of May 1948.

She was described as a spinster, aged twenty-five years. The certificate had been signed by a Doctor John Bewley. I made a note of the doctor’s name, and then turned back a dozen or so pages until I found Macdonald Crosby’s certificate. He had died of brain injuries from gunshot wounds. The doctor had been J. Salzer; the corner, Franklin Lessways. I made more notes, and then, leaving the file where it was, tramped over to the clerk who was watching me with lazy curiosity.

“Can you get someone to put that file back?” I asked, propping myself up against the counter. “I’m not as strong as I thought I was.”

“That’s all right, Mr. Malloy.”

“Another thing: who’s Dr. John Bewley, and where does he live?”

“He has a little place on Skyline Avenue,” the clerk told me. “Don’t go to him if you want a good doctor.”

“What’s the matter with him?”

The clerk lifted tired shoulders.

“Just old. Fifty years ago he might have been all right. A horse-and-buggy doctor. I guess he thinks trepanning is something to do with opening a can of beans.”

“Well, isn’t it?”

The clerk laughed.

“Depends on whose head we’re talking about.”

“Yeah. So he’s just an old washed-up croaker, huh?”

“That describes him. Still, he’s not doing any harm. I don’t suppose he has more than a dozen patients now.” He scratched the side of his ear and looked owlishly at me. “Working on something?”

“I never work,” I said. “See you some time. So long.”

I went down the steps into the hard sunlight, slowly and thoughtfully. A girl worth a million dies suddenly and they call in an old horse-and-buggy man. Not quite the millionaire touch. One would have expected a fleet of the most expensive medicine men in town to have been in on a kill as important as hers.

I crawled into the Buick and trod on the starter. Parked against the traffic, across the way, was an olive-green Dodge limousine. Seated behind the wheel was a man in a fawn-coloured hat, around which was a plaited cord. He was reading a newspaper. I wouldn’t have noticed him or the car if he hadn’t looked up suddenly and, seeing me, hastily tossed the newspaper on to the back seat and started his engine. Then I did look at him, wondering why he had so suddenly lost interest in his paper. He seemed a big man with shoulders about as wide as a barn door. His head sat squarely on his shoulders without any sign of a neck. He wore a pencil-lined black moustache and his eyes were hooded. His nose and one ear had been hit very hard at one time and had never fully recovered. He looked the kind of tough you see so often in a Warner Brothers’ tough movie: the kind who make a drop-cloth for Humphrey Bogart.

I steered the Buick into the stream of traffic and drove East, up Centre Avenue, not hurrying, and keeping one eye on the driving-mirror.

The Dodge forced itself against the West-going traffic, did a U-turn while horns honked and drivers cursed and came a

fter me. I wouldn’t have believed it possible for anyone to have done that on Centre Avenue and get away with it, but apparently the cops were either asleep or it was too hot to bother.

At Westwood Avenue intersection I again looked into the mirror. The Dodge was right there on my tail. I could see the driver lounging behind the wheel, a cheroot gripped between his teeth, one elbow and arm on the rolled-down window. I pulled ahead so I could read his registration number, and committed it to memory. If he was tailing me he was making a very bad job of it. I put on speed on Hollywood Avenue and went to the top at sixty-five. The Dodge, after a moment’s hesitation, jumped forward and roared behind me. At Foothills Boulevard I swung to the kerb and pulled up sharply. The Dodge went by. The driver didn’t look in my direction. He went on towards the Los Angeles and San Francisco Highway.

I wrote down the registration on the old envelope along with Doc Bewley’s name and stowed it carefully away in my hip pocket. Then I started the Buick rolling again and drove down Skyline Avenue. Halfway down I spotted a brass plate glittering in the sun. It was attached to a low, wooden gate which guarded a small garden and a double-fronted bungalow of Canadian pine wood. A modest, quiet little place; almost a slum beside the other ultramodern houses on either side of it.

I pulled up and leaned out of the window. But, at that distance it was impossible to read the worn engraving on the plate. I got out of the car and had a closer look. Even then it wasn’t easy to decipher, but I made out enough to tell me this was Dr. John Bewley’s residence.

As I groped for the latch of the gate, the olive-green Dodge came sneaking down the road and went past. The driver didn’t appear to look my way, but I knew he had seen me and where I was going. I paused to look after the car. It went down the road fast and I lost sight of it when it swung into Westwood Avenue.

I pushed my hat to the back of my head, took out a packet of Lucky Strike, lit up and stowed the package away. Then I lifted the latch of the gate and walked down the gravel path towards the bungalow.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

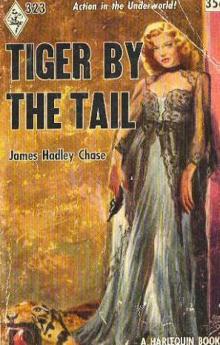

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail