- Home

- James Hadley Chase

Vulture Is a Patient Bird Page 19

Vulture Is a Patient Bird Read online

Page 19

Fennel did as he was told, put on his shoes and came back to where Garry was anxiously watching Gaye.

“I guess she’s picked up some bug,” Fennel said indifferently. “Well come on, Edwards, let’s go. Those black bastards may be right behind us.”

“Look around and see if you can find two straight branches. We could make a stretcher with our shirts.”

Fennel stared at him.

“You out of your head? Do you imagine I’m going to help carry that bitch through this goddamn jungle and in this heat when those blacks are racing after us? You carry her if you want to, but I’m not.”

Garry looked up at him, his face hardening.

“Are you saying we should leave her here?”

“Why not? What’s she to us? You’re wasting time. Leave her and get going.”

Garry stood up.

“You go. I’m staying with her. Go on… get out!”

Fennel licked his lips as he stared at Garry.

“I want the compass and the ring,” he said softly.

“You get neither! Get out!”

For a man of his bulk, Fennel could move very quickly. His fist flashed out as he jumped forward, but Garry was expecting just this move. He ducked under the fist and hooked Fennel to the jaw: a crushing punch that flattened Fennel.

“I said get out!” Garry snapped.

Fennel had landed on his back, his arms flung wide. His groping fingers closed on a rock, half-hidden in the grass. He gripped it and with a violent movement, hurled it at Garry. The rock smashed against the side of Garry’s head and he went down as if he had been pole-axed.

His jaw throbbing, Fennel struggled to his feet. He approached Garry cautiously and bent over him. Satisfied that Garry was unconscious, Fennel slipped his fingers into Garry’s shirt pocket and found the compass. He crossed over to where Gaye was lying. Catching hold of her right wrist, he pulled the Borgia ring off her thumb. As he did so, she opened her eyes and seeing his face close to hers, she struck at him with her left hand.

It was such a feeble blow Fennel scarcely felt it. He grinned viciously.

“Good-bye, baby,” he said, bending over her. “I hope you suffer. I’m taking the compass and the ring. You two will never get out of here alive. If you had been nice to me, I would have been nice to you. You asked for it and you’re getting it.” He stood up. “If the Zulus don’t find you, the vultures will. So long, and have a wonderful time while it lasts.”

Gaye closed her eyes. He doubted if she had understood half what he had said, but it gave him a lot of satisfaction to have said it.

He picked up the rucksack containing the last of the food and the water bottle, checked the compass for his bearing, then set off fast into the dark steamy heat of the jungle.

Garry stirred and opened his eyes. A shadow passed over his face, then another. He looked up at the tree. He could see through the foliage, heavy grey clouds moving sluggishly westward. Then he saw two vultures settling heavily on the topmost branch of the tree, bearing it down under their combined weight. Their bald, obscene looking heads, the cruel, hooked beaks and their hunched shoulders sent a chill of fear through him.

His head throbbed and when he touched the side of his face, he felt encrusted blood. He was still dazed, but after resting a few minutes, his mind began to clear. His hand went to his shirt pocket and he found the compass gone. He struggled to his feet and went unsteadily over to where Gaye was lying. She now looked flushed and her forehead was covered with beads of sweat. She seemed to be either sleeping or unconscious. He looked at her right hand. It was no surprise to see the ring was missing.

He squatted down beside her and considered his position. He had possibly fifteen kilometres of jungle swamp ahead of him before he reached the boundary exit. He glanced towards the rucksacks and saw the rucksack containing the food was also missing. Without food or water, he couldn’t hope to last long. His watch told him it was i6.00 hrs. The Zulus had been searching for them now for nine hours. Had the rain washed out their tracks? If it hadn’t, he could expect the Zulus to appear any time now.

Had he been alone, he would have gone off at once in the hope of overtaking Fennel, but he couldn’t leave Gaye.

He looked down at her. Maybe Fennel had been right about her picking up a bug. She looked very ill and was obviously running a high temperature. As he watched her she slowly opened her eyes. It took her a few moments to get him into focus, then she frowned, moving as if in pain.

“You’re hurt,” she said huskily.

“It’s all right.” He took her hot hand in his. “Don’t worry about that.”

“He’s taken the compass and the ring.”

“I know. Take it easy. Don’t worry about anything.”

The sudden crashing of branches overhead startled them and both looked up. One of the vultures had dropped from the upper branch to a lower one and was stretching its mangy neck, peering down at them.

Getting to his feet, Garry picked up the blood-stained rock and heaved it up into the tree. The rock whistled by the vulture. It flew off with a great flapping of wings and rustling of leaves.

“It knows I am dying,” Gaye said, her voice breaking. “Garry! I’m so frightened.”

“You’re not dying! You’ve caught a bug of some sort. In a day or so, you’ll be fine.”

She looked at him, and his heart sank at the fear and hopelessness he saw in her eyes.

“There’s nothing you can do for me,” she said. “Leave me. You must think of yourself, Garry. It won’t be long for me. I don’t know what it is, but it’s as if something is creeping up inside me, killing me piecemeal. My feet are so cold, yet the rest of me burns.”

Garry felt her naked feet. They were ice cold.

“Of course I’m not leaving you. Are you thirsty?”

“No. I have no feeling in my throat.” She closed her eyes, shivering. “You must go, Garry. If they caught you…”

It dawned on him then that she could be dying. With her by his side, the attempt to get through the jungle wouldn’t have daunted him, but realizing he might have to do it alone sent a prickle of panic through him.

“Do you believe in God?” she asked.

“Sometimes.”

He hesitated.

“For both of us this is really the time to believe, isn’t it?”

“You’re going to be all right.”

“Isn’t it?”

“I guess so.”

There was a sudden disturbance in the tree above them as the vultures settled again.

She caught hold of his hand.

“You really mean you are going to stay with me?”

“Yes, darling. I’m staying.”

“Thank you, Garry, you’re sweet. I won’t keep you long.” She looked up at the vultures who were looking down at her. “Promise me something.”

“Anything.”

“You won’t be able to bury me. You can’t dig with your bare hands, darling, can you? Put me in the river, please. I don’t mind the crocodiles, but the vultures…”

“It’s not coming to that. You rest now. By tomorrow, you’ll be fine.”

“Promise, Garry.”

“All right, I promise, but…”

She interrupted him.

“You were right when you told me not to pin everything on money. If money hadn’t meant so much to me I wouldn’t be here now. Garry, have you a piece of paper and a pen? I want to make my will.”

“Now, look, Gaye, you’ve got to stop being morbid.”

She began to cry helplessly.

“Garry… please… you don’t know what an effort it is even to talk. I hurt so inside. Please let me make my will.”

He went to his rucksack and found a notebook and a biro.

“I must do it myself,” she said. “The manager of the Swiss bank knows my handwriting. Prop me up, Garry.”

As he raised her and supported her, she caught her breath in a sobbing moan of pain. It took her a lo

ng time to write the letter, but finally it was done.

“Everything I have, Garry darling, is for you. There’s over $100,000 in securities in my numbered account in Bern. Go and see Dr. Kirst. He’s the director there. Tell him what has happened… tell him everything and especially tell him about Kahlenberg’s museum. He’ll know what to do and keep you clear. Give him this will and he will arrange everything for you.”

“All right… you’re going to be all right, Gaye. Rest now,” and Garry kissed her.

Three hours later, as the sun, a red burning ball in the sky, sank behind the trees, Gaye drifted out of life into death. With the deadly scratch she hadn’t noticed, the Borgia ring claimed yet another victim.

Fennel had been walking fast now for the past two hours. From time to time, swamp land had made him take a wide detour, wasting time and energy. Once he had floundered up to his knees in stinking wet mud when the ground had given under his feet. He had had a desperate struggle to extricate himself: a struggle that left him exhausted.

The silence in the jungle, the loneliness and the heat all bothered him but he kept reassuring himself that he couldn’t now be far from the boundary exit and then his troubles would be over.

He kept thinking of the triumphant moment when he would walk into Shalik’s office and tell him he had the ring. If Shalik imagined he was going to get the ring for nine thousand dollars, he was in for a surprise. Fennel had already made up his mind he wouldn’t part with the ring unless Shalik paid him the full amount the other three and he would have shared… thirty-six thousand dollars. With any luck, in another four or five days, he would be back in London. He would collect the money and leave immediately for Nice. He was due a damn good vacation after this caper, he told himself. When he was tired of Nice, he would hire a yacht, find some bird and do a cruise along the Med., stopping in at the harbours along the coast for a meal and a look around: an ideal vacation and safe from Moroni.

He had now dismissed Gaye and Garry from his mind, never doubting he had seen the last of them. The stupid, stuck-up bitch had asked for trouble. No bird ever turned him down without regretting it. He wished Ken were with him. He frowned as he thought of the way Ken had died. With Ken, he would have felt much more sure of himself. Now, the sun was going down and the jungle was getting unpleasantly dark. He decided it was time to stop for the night. He hurried forward, looking for a clearing where he could get off the narrow track. After some searching, he found what he was looking for: a patch of coarse grass, clear of shrubs with a tree under which he could shelter if it rained.

He put down his rucksack and paused to wonder if he dare light a fire. He decided the risk was negligible and set about gathering sticks and kindling. When he had collected a large heap by the tree, he got the fire going, then sat down, his back resting against the tree. He was hungry and he opened the rucksack and took stock. There were three cans of stewed steak, two cans of beans and a can of steak pie. Nodding his satisfaction, he opened the can of steak pie. When he had finished the meal, he lit a cigarette, threw more sticks on the fire and relaxed.

Now he was sitting still, he became aware of the noises in the jungle: soft, disturbing and distracting sounds: leaves rustled, some animal growled faintly in the distance: Fennel wondered if it were a leopard. In the trees he could hear a sudden chatter of hidden monkeys start up and immediately cease. Some big birds flapped overhead.

He finished his cigarette, added more still 4 to the fire and stretched out. The dampness had penetrated his clothes and he wondered if he would sleep. He closed his eyes. Immediately, the distracting sounds of the jungle became amplified and alarming. He sat up, his eyes searching beyond the light of the fire into the outer darkness.

Suppose the Zulus had spotted the fire and were creeping up on him? he thought.

They hammer a skewer into your lower intestine, Kahlenberg had said.

Fennel felt cold sweat break out on his face.

He had been crazy to have lit the fire. It could be spotted from a long distance away by the sharp-eyed savages. He grabbed up a big stick and scattered the fire. Then getting to his feet, he stamped out the burning embers until the sparks had died in the wet grass. Then it was even worse because the darkness descended on him like a hot, smothering, black cloak. He groped for the tree, sat down, resting his back against it and peered fearfully forward, but now it was as if he were blind. He could see nothing.

He remained like that for more than an hour, listening and starting with every sound. But finally he began to nod to sleep. He was suddenly too exhausted to care.

How long he slept, he didn’t know, but he woke with a start, his heart racing. He was sure he was no longer alone. His built-in instinct for danger had sounded an emergency alarm in his mind. He groped in the darkness and found the thick stick with which he had scattered the fire. He gripped it while he listened.

Quite close… not more than five metres from him, there was a distinct sound of something moving through the carpet of leaves. He had his flashlight by him and picking it up, his racing heart half suffocating him, he pointed the torch in the direction of the sound, then pressed the button.

The powerful beam lit up a big crouching animal that Fennel recognized by its fox-like head and its filthy fawn and black spotted fur to be a fully grown dog hyena.

He had only a brief glimpse of the animal before it disappeared into the thicket on the far side of the track, but that glimpse was enough to bring Fennel to his feet, panic stricken.

He remembered a conversation he had had with Ken while they were in the Land Rover on the first easy leg of the journey to Kahlenberg’s estate.

“I get along with all the animals out here except the hyena,” Ken had said. “He is a filthy brute. Not many people know this scavenger has the most powerful teeth and jaws of any animal. He can crack the thigh of a domestic cow the way you crack a nut. Besides being dangerous, he is an abject coward. He seldom moves except by night, and he will go miles following a scent and has infinite patience to wait to catch his prey unawares.”

With his eyes bolting out of his head, his hand shaking, Fennel played the beam of the flashlight into the thicket. For a brief moment he saw the animal glaring at him, then vanish.

He has infinite patience to wait to catch his prey unawares.

Fennel knew there was no further sleep for him that night, and he looked at his wristwatch. The time was 03.00 hrs. Another hour before it began to get light and he could move. Not daring to waste the battery, he turned off the flashlight. Sitting down, he leaned against the tree and listened.

From out of the darkness came a horrifying, maniacal laugh that chilled his blood and raised the hairs on the nape of his neck. The horrible, indescribably frightening sound was repeated… the howl of a starving hyena.

Fennel longed for Ken’s company. He even longed for Garry’s company. Sitting in total darkness, knowing the stinking beast might be creeping slowly on its mangy belly, his powerful jaws slavering, towards him, he remained motionless, tense and straining to hear the slightest sound. He remained like that, his body aching for sleep, his mind feverish with panic for the next hour.

Whenever he dozed off, the howl of the hyena brought him awake and cursing. If only he had the Springfield or even an assigai, he thought, but he had nothing with which to defend himself except the thick stick which he was sure would be useless if the beast sprang at him.

When dawn finally came, Fennel was almost a wreck. His legs were stiff and his muscles ached. His body cried out for rest. He dragged himself upright, picked up his rucksack, and after assuring himself there was no sign of the hyena, he set off along the jungle track, again heading south. Although he forced himself along, his speed had slowed and he wasn’t covering the ground as he had the previous day. He wished he knew how much further he had to go before he reached the boundary exit. The jungle was as dense as it had been yesterday and showed no sign of clearing. He walked for two hours, then decided to rest and eat. Sitting

on a fallen tree, he opened a can of beans and ate them slowly, then he took a small drink from the water bottle. He smoked a cigarette, reluctant to move, but he knew he was dangerously wasting time. With an effort he got to his feet and set off again. Having walked for some five kilometres, he paused to check the compass. From the reading, he realized with dismay that he was now walking south-west instead of due south. The track had been curving slightly, taking him away from his direction and he hadn’t noticed it.

Cursing, he fixed his bearing and saw that to move in the right direction, he would have to leave the path and force his way through the thick, evil smelling undergrowth. He hesitated, remembering what Ken had said about snakes.

It would be a hell of a thing, he thought, to have got this far and then to get bitten by a snake. Gripping his stick, he moved into the long, matted grass, feeling the sharp blades of the grass scratching at his bare legs. The sun was coming up, and already the heat was oppressive. The .going was deadly slow now, ,and sweat began to stream off him as he slashed his way through the grass and tangled undergrowth with his stick, cursing aloud. Ahead of him, after a kilometre of exhausting struggle, he saw a wide open plain and he gasped with relief. He broke through to it, but almost immediately, his feet sank up to his ankles in wet, clinging mud and he backed away, returning to the undergrowth. The plain he had imagined would be so easy to cross was nothing more than a dangerous swamp. He was now forced to go around the swamp, making an exhausting detour, feeling his strength slowly ebbing from him as he struggled on in the breathless heat.

He now began to wonder if he would ever get out of this hellish place. He would have to rest again, he told himself. That was the trouble. He was worn out after a sleepless night. Maybe if he could sleep for three or four hours, he would get back his strength which he had always taken for granted and relied on.

It was a risk, he thought, but a risk that had to be taken if he was to conserve his strength for the last lap through the swamp. He remembered Ken had said hyenas only hunted at night. The beast was probably miles away by now. He would have to find somewhere to hide before he dare have the sleep his body was aching for. He dragged himself on until he saw a big, fallen tree some way from the track and surrounded by shrubs. This seemed as good a place as any, and when he reached it he found the ground on the far side of the trunk reasonably dry. Thankfully, he lay down. He made a pillow of his rucksack, placed the rucksack of food near at hand and the thick stick by his side. He lowered his head on the rucksack, stretched out and in a few moments, he was asleep.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

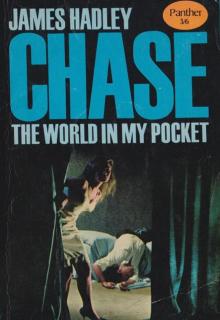

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

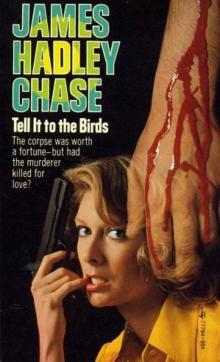

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

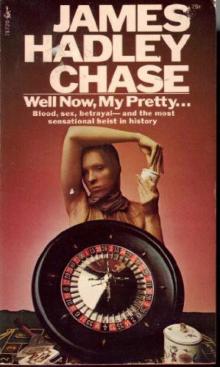

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

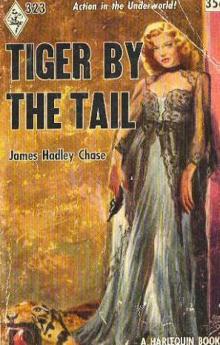

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail