- Home

- James Hadley Chase

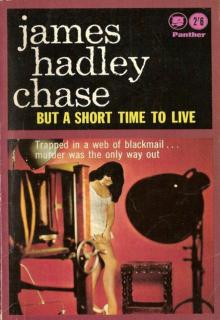

1951 - But a Short Time to Live Page 16

1951 - But a Short Time to Live Read online

Page 16

If only he could talk his worries over with Ron now! He saw Ron regularly once a month, but it was like seeing a stranger. Ron was so quiet, just sitting in his wheeled chair, scarcely saying a word, brooding all the time, a fixed stare in his eyes.

Sheila was getting a divorce. Ron didn't seem to grasp that He didn't seem to grasp anything. The only time a flicker of interest had shown on his face was when Clair went with Harry to see him. She had only been once.

"It's too damned depressing ever to go again," she said afterwards.

Ron had looked at her intently for some moments, and then said unexpectedly, "You're just what I imagined you'd be. Look after him, won't you? He's not much good at looking after himself," and then he seemed to lose interest again, and the rest of the time they spent with him was just like any of the other visits Harry made.

Harry lit a cigarette and reached for his book. He had a couple of hours yet before he went to bed. It was lonely in this big luxurious flat. It was all right when Clair was here, but when she had gone, the place seemed too big. It seemed unfriendly too, almost as if it resented Harry.

He would read until eight-thirty. Then he would listen to Twenty Questions on the wireless. Clair would be in the middle of her act by now. Lehmann had said he thought the show would run another year.

What would happen then? In that time the studio should be established. But would it? He tried to get his mind off his worries, but the book didn't hold him and impatiently he put it down. As he reached for another cigarette the front door bell rang, making him start. For a moment or so he sat still, wondering who it could be. No one ever called when Clair was at the theatre. He got up and went into the hall as the bell rang again.

He opened the front door.

For a moment he didn't recognise the tall fat man who stood in the passage, his navy blue homburg hat tilted rakishly over one eye; then he felt a prickle run up his spine. It was Robert Brady.

chapter twenty-four

Faintly, from down the passage, Harry could hear Kenneth Home introducing the Twenty Questions' team. He wanted to shut the door and turn on his own wireless: to shut out this apparition from the past and pretend he wasn't there.

In a voice he didn't recognise as his own, he said, "What do you want?"

"It's time we had a little talk," Brady said, and smiled, showing his gold-capped teeth. He reminded Harry of a well-groomed pig with his pink and white flesh, his small bright eyes and his heavy whistling breathing.

"What about?" Harry said, standing squarely in the doorway. "I've nothing to say to you, and I don't want to listen to you."

Brady waved his cigar airily.

"There are lots of things we don't want to do," he said, lifting his massive shoulders, "but we have to put up with them. If you think for a moment it may occur to you that I could make a lot of trouble for you. Hadn't you better hear what I have to say?"

"Yes, he could make trouble," Harry thought, his heart sinking.

"Well, come in," he said curtly and stood aside.

Brady entered the hall and walked into the sitting-room. He stood looking round, his eyebrows raised, his lips pursed.

"Well, well," he said. "You've come up in the world, haven't you, my friend? Very different from peddling pictures in the street."

"Say what you have to say and get out," Harry said, blood rising in his face.

Brady took off his hat and dropped it on to the table. He walked over to the fireplace and took up a position on the rug before the fire.

"Damned clever girl, isn't she?" he said. "But clever as she is I never thought she'd do as well as this. Park Lane! My stars! When I first met her she was walking the streets."

Harry took a sudden step forward. He had a furious urge to smash his fist into the fat pig-like face.

"Be careful, my friend," Brady cautioned, moving out of Harry's reach. "You can't afford to be dramatic. This is not going to be a brawl, you know. You'll have to be subtle and use whatever brains you have if you're going to crawl out of this mess. And I don't think you'll succeed however much you wriggle."

Harry restrained himself. Better hear what he had to say. There would be time enough to hit him when he had finished.

"That's better," Brady went on, watching him. "Forget the violence. If you attempt to hit me it'll only make it worse for Clair. Sit down." He sat down himself in the most comfortable chair in the room and stretched out his massive legs. "I think I'll have a whisky. You have whisky, of course? She always knows where to get everything that's in short supply."

Harry didn't move.

"Say what you have to say and get out!"

"You know, this attitude of yours won't do at all," Brady said, knocking cigar ash on to the carpet. "You'll have to be brought to heel. Don't you realise that a word from me would get Clair tossed out of the theatre? Then you wouldn't be living quite so well, would you?"

"A word about what?" Harry demanded.

"Well, after all she has been in prison. The newspapers would be interested. A jailbird isn't a great attraction on the stage. I don't think Simpson could afford to make an exhibition of her."

After a moment's hesitation Harry went to the cellaret and took out a bottle of whisky, a glass and a soda siphon and set them on the table beside Brady.

"That's much better," Brady said and poured himself a stiff drink. "That's much more like it."

Harry sat down. He was calmer now. The thing to do, he told himself, was to hear what Brady had to say. If it was blackmail he would go at once to Inspector Parkins. He would know how to deal with him.

"This is really astonishing," Brady went on, after he had tasted the whisky. "She knows how to live, doesn't she? Just as if she were born to it, instead of spending most of her life in a slum. Of course she has me to thank for it, but I will say she was an apt pupil. When I first met her she had a squalid little room in Shepherd Market. Any Tom, Dick or Harry could have had her for a pound. I dressed her and taught her the tricks. I got her a flat off Long Acre. I taught her how to pick pockets. She learned quickly." He gave a thin smile. "She turned out to be my best girl. She made me and herself quite a slice of money." He looked at Harry and frowned. "I wonder what she sees in you." He paused to hold the glass of whisky under his nose, sniffing at it with a look of pleasure on his face. "She was always an impulsive creature. It's an odd thing how these tarts fall for some down-at-the-heel rat. I've seen it happen dozens of times. I suppose it's a kind of frustrated mother instinct. But most of them do it. Most of them have some worthless little horror feeding on them, taking their money, whining for clothes like the parasites they are. Still, I can't understand why she's fallen for you. Usually she goes for the boys with money."

Harry said nothing. He stared at Brady, his face white and set.

"Yes," Brady said. "Boys with the money. Boys like Allan Simpson." He smiled, his small eyes on Harry's face. "But perhaps you don't know about Simpson? I've been watching her. As a matter of fact I've been following her around for the past week or so. She goes once or twice a week to Simpson's flat Perhaps you've never wondered what she did with herself after her act at the Regent finished and before her act at the 22nd began? Two hours to get into mischief. Two hours, to spend with Simpson. Up to her old tricks, of course. She has a knack of getting things out of men. Once a tart, always a tart: the temptation is too strong for them. It's too easy." He glanced round tie room again. "Looks as if she's come off best But perhaps you didn't know?"

"Is that all you have to say?" Harry said, controlling his voice with an effort "Why, no, certainly not. I haven't started yet. I just thought you'd be interested to know how she got the job at the night club. She rolls in the hay with Lehmann too. Not that I blame her. Once you've done that sort of thing for a living you don't look on it as anything out of the way."

"I'm not going to listen to any more of this," Harry said, getting to his feet. "If you don't get out, I'll throw you out!"

Brady laughed.

"D

on't be absurd. Why shouldn't I tell you this? Don't you want to know? Of course you do. A man likes to know how his girl provides for him. There's a name for a man like you. It's not a pretty one, and it carries a six-months' sentence."

"Get out!" Harry said, angrily. "I won't tell you again! Get out!"

"But I have every right to tell you," Brady said calmly. "I'm her husband, too."

Harry felt as if he had received a blow in the face. He took a step back, tried to say something, but the words wouldn't come.

"So she didn't tell you? Well, well, how odd of her," Brady said, smiling. "Odd too she should have married you. I imagined you wouldn't have objected to living on her without marriage."

"Did you say you were her husband?" Harry managed to get out

"Certainly. I've been her husband for more than five years."

"You're lying!"

"Do you think so? A pity. Of course we didn't live together after the first year. I have no idea why we did marry. We must have been drunk at the time. It was during the blitz, and while the bombs fell she was seldom sober; nor was I for that matter. It wasn't much fun for her to walk the streets with bombs and shrapnel coming down. The only thing that kept her going was booze." His fat finger tapped more ash on to the carpet. "If you don't believe me, you can always go to Somerset House and check the records. She called herself Clair Selwyn then. Her mother's name, I believe."

"I don't believe a word of it!" Harry burst out. "She'd never marry a swine like you. Get out! If you come here again I'll tell the police!"

"My poor fellow," Brady said, smiling. "If I remember rightly the sentence for bigamy is about two years. Imagine how she'd hate that after all this luxury. I think we'd better leave the police out of this, don't you?"

Harry went to the door and threw it open.

"Get out!"

Brady finished his drink and stood up. He was completely unruffled.

"There's no point in staying any longer," he said and picked up his hat. "But I'll be back tomorrow afternoon. Tell her to expect me. I want money, of course. So long as she pays I'll keep quiet. That car of hers is fascinating, isn't it?" He looked round the door admiringly. "Yes, she's done remarkably well. I should be able to shake her down for quite a bit." He moved to the door. "Bad luck for you, my friend. By the time I've finished with her there won't be a lot left for you."

He walked through the doorway, opened the front door, glanced over his shoulder to nod to Harry, then went away, whistling softly under his breath.

chapter twenty-five

Clair came into the room, bringing with her a breath of cold air, and her fur coat sparkled with rain.

"Why, Harry! You still up? Why aren't you in bed?" She paused, sniffed, looked quickly at him. Have you been smoking a cigar?"

Harry was sitting before the fire. Innumerable cigarette butts lay in the hearth. A cigarette burned between his nicotine-stained fingers.

"Brady's been here," he said, not looking at her.

She was moving to the fire, stripping off her gloves as he spoke, and his words brought her to an abrupt standstill.

"Here?" she said, and her face stiffened into an expressionless mask.

He faced her and the sight of the hard, stony face, the bleak set of the painted mouth, the still, glittering eyes shocked him. He had told her a long time ago that he knew a tart when he saw one. He had said she wasn't like one in any way, but she was now. There was no mistaking the look he had seen so often on the faces of the women of the West End: that strange blend of wooden hardness and callousness that make them look subhuman.

"Yes," he said, and looked away.

Slowly, as if she wasn't aware what she was doing, she put her hat, gloves and handbag on the table. Then she opened the cedar-wood box, took out a cigarette and lit it "What did he want?" she asked. Even her voice sounded wooden and harsh.

"Can't you guess? Come and sit down. He's going to make trouble."

Instead of sitting down, she went to the cellaret, brought a glass and poured herself a drink from the bottle of whisky that still stood on the table. Although he wasn't looking at her he could tell how unsteady her hand was by the rattle of the bottle neck against the glass.

"He said you married him about five years ago," Harry went on. "Is it true?"

She came slowly to the fire and sat in the easy chair opposite Harry's.

"Is it true?" he repeated after a long silence.

"Yes, it's true," she said. "I heard he had gone to America. I thought I'd never see him again." She drank some of the whisky and put the glass on the hearth kerb. "I'm sorry, Harry. You wanted it so badly. I didn't want to disappoint you."

"I see," Harry said, and stared in the fire for a long moment. "Oh, well, it's too late to be sorry about it. I understand, of course. It was my fault for pressing you. I wish you had told me, Clair. Couldn't you have trusted me?"

"I didn't want to lose you," she said sullenly.

"He wants money. He's coming to see you tomorrow afternoon."

She didn't say anything and he glanced at her. She was staring into the fire. She looked old and worn, somehow shop-soiled, as if her bright, glittering veneer had been stripped away to show what was really underneath.

As she remained silent, he said, "It's blackmail, of course. We could go to the police."

"Let me think a moment," she said sharply.

They remained silent for what seemed to Harry to be a long time. She sat rigid, her cigarette in her lips, the smoke curling in a steady spiral to the ceiling. Only her eyes moved; they shifted continuously, like those of an animal in a trap.

"I want to know exactly what happened," she said suddenly. "Tell me everything. I'm sure he said a lot of filthy things about me, but I want to know everything."

In a cold, flat voice, Harry told her.

"He's been watching you," he concluded. "He says you go quite often to Simpson's flat."

She half-started out of her chair.

"That's a lie, Harry! You don't believe it, do you?"

He looked straight at her, and her eyes shifted.

"I don't want to believe it," he said. "He also said you and Lehmann . . ." He broke off, seeing the trapped expression on her face. "Is it true?"

"I warned you, didn't I?" she said harshly. "I told you I was rotten. Well, I am. I don't make any bones about it. They mean nothing to me. Nothing! All right, I won't lie to you, Harry. I do go to their flats." She reached for another cigarette.

"How could you, Clair?" He got to his feet and began to walk aimlessly about the room. Haven't you any thought for me? I have to mix with them. Why did you do it?"

"How else do you think I got the Regent job? But don't you see, Harry, they can't mean anything to me! You are the only man in my life. Ever since I met you I've wanted to do things for you, but I've only succeeded in making you unhappy. I couldn't help it It was so easy. I knew if I went with them I could handle them."

"You put money before everything," Harry said. "That's where you go wrong. Oh, Clair, why did you do it? We could have been happy if you had left the money side to me. We wouldn't have had a great deal, but we wouldn't have been in this mess."

"I suppose you hate me now," she said in a hard, flat voice. "Well, I don't blame you. What are you going to do? Are you going to walk out on me?"

He went to the window, pushed the curtain aside and stared down into the rain-swept street.

"Harry!" She got up and went to him, putting her hand on his arm. "What are you going to do? Are you going to leave me?"

He shook his head.

"It's all right," he said, not turning. "We'll forget about everything for now except Brady. When we've dealt with him we can tackle our own problem, but not before."

"Does that mean you're going to leave me — in a little while? I must know, Harry. I can't stand the uncertainty. Can't you see a man like Simpson couldn't mean anything to me except what I could get out of him? It's you I love. My whole life's centred around you. A

ll I've done — this place, the car, the money I've made is for you if only you'd accept them. If you're going to leave me, tell me now."

Harry turned and looked helplessly at her.

"How I wish you hadn't done any of this. It's all right, Clair. I'm not going to leave you. I'd be lying if I said it won't make a difference; it will, but I still love you, and if you'll try to change — give up this horrible thirst for money, we'd be so much happier. Can't you see that? Give up the stage, Clair. Let's make a fresh start. What does it matter if we're hard up? Isn't it better to be hard up than in a mess like this?"

"Do you think Brady will let me give this up now?" she asked. He'll want money, and I'll have to earn it. He's like a leech. He'll cling on and suck me dry."

"We'll go to the police. It's the only way to deal with a rat like him."

"The police? I've committed bigamy," Clair said, her voice rising. "How can we go to the police? Do you think I want to go to prison again?"

"But you're not going to give him money, are you?" Harry said, anxiously. "He'll never leave you alone once he knows he can get it out of you. They never do."

"I know I'm not going to prison. I'd kill myself first'

"Clair . . . please—"

"I would! I'd kill myself. I'd rather die than spend a week in prison. You don't know what it's like. It was awful. Worse than I ever imagined. Hellish! Shut away from everything. Made to do beastly chores. Nagged and bullied. Shut up behind bars like an animal. No, that'll never happen to me again. I'm ready this time. I'll kill myself!"

"You mustn't talk like that, Clair," Harry said, shocked. "We haven't the right to end our own lives."

She gave a hard, sneering little smile.

"It's my own life to do what I want with. I know I'll never go to prison again." She turned away.

"Come on, Harry, let's go to bed. It's late and I'm tired." She picked up her hat and gloves and walked into the bedroom. Her shoulders drooped and she walked listlessly. Watching her, Harry felt a pang of pity for her. It was all partly his fault, he thought, following her into the bedroom. He had been weak. It was too late for regrets. Brady now controlled the situation. Unless they could think of some way out, she would either have to go to prison or pay.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

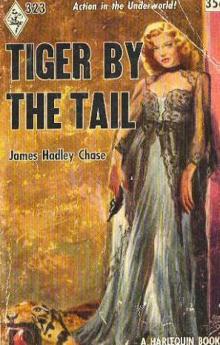

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail