- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid Page 13

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid Read online

Page 13

I heard one of the thugs groan softly, and I knew I hadn’t much time. I stepped up on to the balustrade of the terrace, reached up for the narrow coping running along the edge of the roof, got a grip, then pulled myself upwards.

I have a pretty good head for heights, but while I was dangling in mid-air, I did think of the long, long drop far below.

I got my leg up on the roof, heaved upwards and slid my body on to it. For a long moment I remained there, clutching on to the tiles and wondering if I made one more move if I’d start a slide I wouldn’t be able to stop.

I made the move, got up on hands and knees, and then, very cautiously, I stood up. My crepe-sole shoes afforded a good grip. Bending low, I walked up the tiles to the flat roof and sat down.

There was no skylight. If anyone came after me, he would have to come the way I had, and with a gun in my hand, that made my position for the time being impregnable. I had a magnificent view over the whole of St. Raphael City and I sat admiring it.

Around eight o’clock I heard the club suddenly come to life. Far below big Cadillacs, Packards and Rolls-Royces pulled up outside the hotel entrance. A very slick dance band started up: lights came on on the terrace. I judged it safe to light a cigarette. I decided to wait an hour and then see what I could see.

By nine o’clock the rush was on. Above the precision slickness of the band, I could hear a great buzz of voices and laughter. Now was the time and I stood up.

Going down the sloping roof was a lot more dangerous than going up: one slip and I would shoot over the edge and down on the sidewalk some three hundred feet below.

I moved an inch at a time, squatting on my haunches, digging my heels into the tiles and checking myself with my hands. I reached the edge, got a grip on the coping, got my legs over the edge, twisted off and swung into space.

Away to my right I could see the brilliantly lit terrace with its tables, its elegantly dressed men and women and the regiment of waiters milling around them. I was just in the shadows, and unless anyone came right to the end of the terrace, I couldn’t be seen.

My feet touched the wide ledge that ran below the windows of the offices. I let myself drop: a dangerous move, and as I landed I nearly lost my balance and toppled backwards. But by dropping my head forward I just managed to correct my balance, then I hooked my fingers into the coping and held on while I got my breath back.

The rest was pretty plain sailing. All I had to do was to walk along the ledge and look in the windows as I passed. The first two rooms I came to were empty. They were furnished as offices with desks, typewriters and filing cabinets: everything on the de luxe scale. The third window was much larger. I paused beside it and looked in.

Cordez sat in a high-backed chair before a big glass-topped desk. He was smoking a brown cigarette in a long holder and was checking figures in a ledger.

The room was big and done over in grey and eggshell blue. All the desk fitments were of polished steel. Three big filing cabinets, also of steel, stood along the wall. Near where Cordez was sitting was a big safe.

I kept just out of the stream of light that came through the open window, bending forward so I could peer into the room. Cordez worked quickly. His gold pencil travelled up the rows of figures, casting them with the practised ease of an accountant.

I remained watching him for perhaps ten minutes, and then, just when I was beginning to think I was wasting my time, I heard a knock on the door.

Cordez looked up, called, “Come in,” and then went back to his casting again.

The door opened, and a fat, white-faced man in a well-fitting tuxedo entered. He had a red carnation in his buttonhole and diamonds glittered at his shirt cuffs. He closed the door as if it were made of something very brittle and stood still, waiting, his eyes on Cordez.

When Cordez had finished casting a column, he noted down the total, then looked up.

His expression was coldly hostile.

“Now look, Donaghue,” he said, “if you haven’t any money, get out. I’ve had about all I’m going to take from you.”

The man fingered his perfectly set tie. Sullen hatred showed in his eyes.

“I’ve got the money,” he said, “and don’t give me any of your damned impertinence.” He hauled out a roll of bills from his hip pocket and threw them on the desk. “Here’s a thousand. I’ll have two this time.”

Cordez picked up the roll, straightened it and counted the bills. Then he opened a drawer in his desk and dropped the roll into it. He got to his feet and walked over to the safe. Standing squarely in front of it so his body hid the combination from Donaghue and myself, he twirled the dial and pulled the door open. He reached inside, took something out, closed the safe door and came back to the desk.

He flicked two match-folders across the glass top of the desk so they came to rest before Donaghue.

Donaghue snatched them up, opened them and examined them carefully, then slid them into his vest pocket. He went out without a word, and Cordez returned to his desk. He sat for a long moment staring at the opposite wall, then he picked up his gold pencil and began casting again.

I remained where I was, watching.

During the period of forty minutes, two other people came in: a fat, elderly woman and a young fellow who looked as if he were still at college. They each parted with five hundred dollars for a match-folder. Each time Cordez treated them as if he were doing them a favour. By now it was ten minutes to ten, and I remembered my appointment with Margot Creedy.

I leaned forward and looked down. Ten feet below and to my left I could see a balcony to one of the hotel bedrooms. No lights showed from the window. I decided that would be my safest and easiest way out.

Crouching, I slid past Cordez’s window and arrived immediately above the balcony. Then I sat on the ledge, turned, caught hold of the coping, let myself hang, then dropped.

The french doors were easy enough to force, and a few minutes later I was in the bedroom. I groped my way to the door, opened it and looked cautiously out into a wide, deserted corridor.

Then I set off down the corridor in search of the elevator.

It was as easy as that.

Chapter 9

I

At five minutes after ten o’clock, I saw Margot Creedy come through the hotel’s revolving doors and pause under the brightly lit canopy.

She was wearing an emerald green dress made of sequins, with a plunging neckline, that fitted her like a second skin. Around her throat was a string of big, fat emeralds.

She glittered as she stood there, and she was pretty breathtaking. I was acutely aware of the Buick’s shabbiness as I edged it up to the hotel entrance. I pulled up, slid across the bench seat and got out.

“Hello there,” I said. “I want to be personal and tell you you look wonderful. That’s just for the record. My real opinion is a little too intimate for expression.”

She gave me her small smile. Her eyes were very alive and sparkling.

“I put this on specially for you,” she said. “I’m glad you like it.”

“That’s an understatement: it’s a dazzler. Have you your car here?”

“No. I’ll show you the bungalow, and then perhaps you wouldn’t mind driving me back?”

“Of course I’ll drive you back.”

I held the door open and she got in. I had a brief glimpse of her slender ankles as I shut the door. I went around the car, got in and drove down the drive.

“You turn right and go to the far end of the promenade,” she told me. There were a lot of cars idling along the promenade. It wasn’t possible to do more than twenty miles an hour and then only in short bursts.

The moon was up, the night was warm and the sea and the palms made a nice setting. I was in no hurry.

“From what I hear this Musketeer Club is quite a place,” I said. “Do you go there often?”

“It’s the only place you can go to that isn’t crammed with tourists. Yes, I go there quite a lot. Daddy owns half of it,

so I don’t have to pay the bills. I wouldn’t go there so much if I did.”

“All you’d have to do is to hock one of those emeralds and you could move in there for good.”

She laughed.

“It so happens they don’t belong to me. Daddy allows me to wear them, but they are his. When I want a change, I take them back and he lends me something else. I don’t own anything. Even this dress I really can’t claim as mine.”

“There’s the bungalow you have on lease,” I said, looking at her out of the corners of my eyes.

“It’s not my lease. Daddy bought it.”

“He’ll love his new tenant. I think maybe I’d better skip this idea and not move in.”

“He won’t know. He still thinks I use it.”

“It would come as a surprise if he drops in for a cup of tea, wouldn’t it?”

“He never drops in for anything.”

“Well, if you’re sure about that. So you’re the genuine poor little rich girl?”

She lifted her lovely shoulders.

“Daddy likes to control everything. I never have any money. I have to send him the bills and he settles them.”

“No one ever settles my bills.”

“But no one tells you you shouldn’t have bought this or that, and you can do without these or those, do they?”

“You know if you go on like this, I’ll begin to feel sorry for you, and you wouldn’t want that, would you?”

She laughed again.

“I don’t see why not. I like sympathy. No one ever gives me any.”

“You listen carefully: the drip, drip, drip you hear is my heart bleeding for you,” I said.

We were reaching the quieter part of the promenade now and I was able to increase speed. I shifted into top and moved up to forty miles an hour.

“You don’t believe me, do you?” she said. “Sometimes I’m quite desperate for money.”

“So am I. Now look, you don’t ever have to be desperate for money: not a girl like you. You could make a small fortune as a model. Ever thought of that?”

“Daddy wouldn’t allow me to do it. He is very careful about the dignity of his name. No one would employ me if he told them not to.”

“You’re just stalling. You don’t have to live here. New York would love you.”

“Do you think it would? Turn left here, down that road.”

The headlights picked out a rough, sandy road that seemed to be running right into the sea. I swung the car off the broad promenade and reduced speed. We went down the sandy road into darkness. The headlights cut a white path ahead of us.

“I was just talking: it’s easy to talk,” I said. “You can’t lead other people’s lives. You’ve managed so far. You’ll go on managing.”

“Yes, I suppose I will.”

“This is a little off the beaten track, isn’t it?” I said, as the car bumped over the uneven road. Palm trees on either side blocked out the moon and there was only darkness each side of the headlight beams.

She opened her bag and took out a cigarette and lit it.

“That’s why I wanted it. If you had lived in this town as long as I have, you would welcome a little seclusion. Don’t you like being alone?”

Thinking of a possible visit from Hertz and his thugs, I said with reservation, “Within reason.”

We drove for a quarter of a mile in silence, then the headlights picked out a squat bungalow within twenty yards of the sea.

“Here we are.”

I pulled up.

“Have you a flashlight?” she asked. “We’ll need it until I can find the light switch.”

I got a big flashlight out of the door pocket. We both got out and together we walked up the path to the bungalow’s door.

The moon was brilliant and I could see a mile-long strip of empty sand, palm trees and the sea. In the distance I could see lights of a house that was built up on a rocky hill, projecting into the sea.

“What’s out there?” I asked as Margot opened her bag and hunted for the door key.

“That’s Arrow Point.”

“Those lights from Hahn’s place?”

“Yes.”

She found the key, pushed it into the lock and turned it. The door swung open. She groped, and then a light sprang up on a big luxuriously furnished lounge with a small cocktail bar in the distant corner, a radiogram and television combination, plenty of comfortable lounging chairs, a three-foot wide padded window seat that ran the length of one of the walls and a blue and white mosaic floor.

“This is quite something,” I said, walking in and pausing in the middle of the big room to look around. “Are you sure you mean me to move in here?”

She walked over to the double french doors and threw them open. She touched a light switch and lights came up on a thirty-foot long terrace that had a magnificent view of the sea and the distant lights of St. Raphael.

“Do you like it?”

She came back to stand in the doorway and she again gave me her small bewitching smile. Just to look at her got my blood running around in my veins like a car on a roller coaster.

“It’s terrific.”

I was looking at the bar. There was an assortment of bottles on the shelves. It seemed to me there was every drink you could want there.

“Are those bottles the property of your dad or are they yours?”

“They’re his. I took them from the house. Four bottles at a time.” She smiled. “He has everything. I don’t see why I shouldn’t help myself sometimes, do you?”

She went behind the bar, opened the door of a refrigerator and took out a bottle of champagne.

“Let’s celebrate,” she said. “Here, you open it. I’ll get the glasses.”

She went out of the lounge. I broke the wire around the cork of the bottle and, as she returned with two champagne glasses on a tray, I eased the cork out. I poured the wine and we touched glasses.

“What do we celebrate?” I asked.

“Our meeting,” she said, her eyes sparkling at me. “You’re the first man I’ve met who doesn’t care if I’m rich or poor.”

“Now wait a minute . . . what makes you think that?”

She drank the champagne and flourished the empty glass.

“I can tell. Now go and look at your new home and tell me what you think of it.”

I put my glass down.

“Where do I begin?”

“The bedroom is through there to the left.”

We looked at each other. There was an expression in her eyes that could have meant anything.

I went to look at the bedroom, finding I was a little short of breath. I told myself I was letting my imagination run away with me, but the feeling that she wasn’t here merely to show me the bungalow persisted.

It was a nice bedroom: a double bed, closets and a mosaic floor. The closets were full of her clothes. The room was decorated in pale green and fawn.

The bathroom was right next door and looked as if it had been built for a Cecil B. de Mille movie with a sunken bath and a shower cabinet in pale blue and black.

I returned to the lounge.

Margot was lying full length on the window seat, her head supported by two cushions. She was staring out across the expanse of moonlit sea.

“Do you like it?” she asked, without looking at me.

“Yes. Are you quite sure you want me to have it?”

“Why not? I don’t use it now.”

“You have your things here still.”

“There’s nothing I want immediately. I’m a little bored with them. Later, I’ll use them again. I like giving clothes a rest. There’s plenty of room for your things.”

I sat in a lounging chair by her. Having her alone in this bungalow gave me a feeling of acute excitement. She turned her head and looked at me, then she said, “Are you making any progress with your murder?”

“I don’t think I am, but you can’t expect me to keep my mind on my job with this sort of thing happening t

o me, can you?”

“What is happening to you?”

“This—the bungalow. And, of course, you. . .”

“Am I so disturbing then?”

“You could be. You are.”

She looked at me.

“But then so are you.”

There was a long pause, then she swung her long legs off the window seat.

“I’m going to have a swim. Coming?”

“Why sure.” I got up. “I’ll get my bag. It’s in the car.”

Leaving her, I went out into the darkness, got my bag out of the car and came back.

I carried the bag into the bedroom where I found her standing before the full—length mirror. She had taken off her dress and she had on now a white negligée. She was looking at herself, her hands lifting her hair off her shoulders.

“You don’t have to do that,” I said, setting down the bag. “I’ll do it for you.”

She turned slowly. There was that look in her eyes I’ve seen from time to time in the eyes of a woman who is making a proposal.

“You think I’m beautiful?”

“More than that.”

I felt myself sliding over the edge. I made a poor attempt to stop this from developing into something I could be sorry about in the morning, by saying, “Maybe we’d better skip the swim and I’ll take you home.” I was aware of feeling suddenly short of breath. “We might be sorry. . .”

She shook her head.

“Don’t say that. I’m never sorry for anything I do.” Still looking at me, she walked slowly towards me.

II

Give me a cigarette,” Margot said from out of the darkness. I reached for my pack on the bedside table, shook one out, gave it to her, then flicked my lighter alight. In the tiny flame, I could see her with her golden head resting on the pillow. There was a relaxed, peaceful expression on her face and she looked at me, our eyes meeting above the flame and she smiled.

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

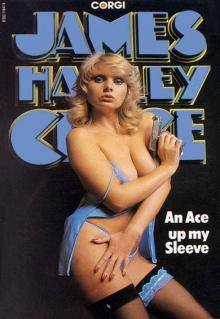

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

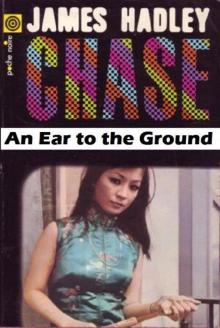

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

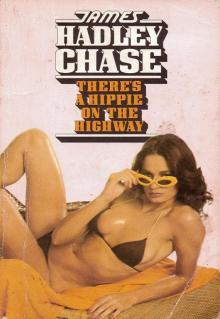

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

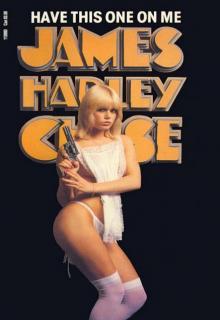

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail