- Home

- James Hadley Chase

1971 - Want to Stay Alive Page 12

1971 - Want to Stay Alive Read online

Page 12

“My son has a difficult temper, sir,” the old man said huskily. “He has been difficult at home. I had to speak to our doctor. He did speak to Poke, but . . .young people are difficult these days.”

“Who is your doctor?”

“My doctor?” Toholo looked up. “Why, Dr. Wanniki.”

Lepski took out his notebook and wrote the name down, then he leaned forward and looked directly at Toholo.

“Is your son sick, Mr. Toholo?”

The old man suddenly sank onto a stool and put his hands to his face.

“Yes, God help his mother and me . . . yes, he could be.”

SIX

While the Homicide squad were systematically turning over the two cabins at the Welcome motel, Lepski drove back to headquarters.

With the siren screaming, Lepski stormed down the busy boulevard, imagining himself to be Jim Clark coming into the last lap. If there was one thing Lepski loved more than anything else it was to cut a swathe through the Rolls, and Bentleys and the Cadillacs of the rich. He watched the sleek, glittering cars pull to one side in panic as his siren hit their drivers. He flashed by the wealthy with their fat plum-coloured faces and their immaculate clothes and grinned his wolf’s grin. This was, he thought, as he whipped his car by a semi-paralysed owner of a Silver Shadow Rolls, a compensation for the dreary, hard toil he had saddled himself with as a police officer.

He had to restrain himself from leaning out of his car window and yelling, “Up yours,” as he swept down the boulevard.

He arrived outside headquarters, swept through the gateway and into the police yard. He shut off the siren, wiped his face with the back of his hand and scrambled out of the car. He ran across the yard and started up the stairs, then suddenly he realised how tired he was.

He paused for a moment to think. It occurred to him he hadn’t been home for two nights and for fifty-eight hours, he hadn’t thought of his wife. He also realised he had had only four hours’ sleep since he had left her and those four hours had been spent on a truckle bed at headquarters.

He shook his head, then started up the steps again. He arrived in the Charge room where Sergeant Charlie Tanner was coping with the everyday events of a busy cop house.

“Charlie! Did you think to call my wife?” Lepski demanded, coming to a skidding stop before Tanner’s desk.

“How could I forget?” Tanner said with some bitterness. “I didn’t have to call her. She has been calling me! You’ll have to speak to her, Tom. She’s blocking our lines.”

“Yeah.” Lepski ran his fingers through his hair. “Did she sound worked up?”

Tanner considered this while he sucked the end of his biro.

“I wouldn’t know what you call worked up,” he said finally, “but to me, she sounded like a tiger with a bee up its arse.”

Lepski closed his eyes, then opened them.

“Look, Charlie, be a pal. Call her: tell her I’m working nonstop. Will you do that for me?”

“Not me!” Tanner said firmly. “I want to keep my ear drums intact.”

Lepski released a snort down his nostrils that would have startled El Cordes.

“Who cares about your goddamn ear drums? Call her! Didn’t I call your wife when you had your back to the wall? Didn’t I?”

Tanner wilted. He remembered the awful occasion when he had had it off with a strawberry blonde and Lepski, by barefaced lying, had saved his marriage.

“That’s blackmail, Tom!”

“So go ahead and file charges,” Lepski snarled. “Call Carroll and pour the oil,” then he started up the stairs to the Detectives’ room.

Within minutes he was reporting to Captain Terrell with Beigler sitting in.

“Okay, Tom, you go talk to this doctor . . . what’s his name. Wanniki? If this boy is as sick as his father thinks he is then he must be our number one.” Terrell turned to Beigler. “Get someone down to Toholo’s home. We might find a photograph of this boy and we could find his finger prints.” He got to his feet. I’ll go down to the Fifty Club and talk to some of the members.”

As Lepski started down the stairs, passing the Charge room, he saw Tanner waving frantically as he held out the telephone receiver.

Lepski pulled up short, skidding on his heels.

“What is it?”

“Your wife,” Tanner said.

One look at Tanner’s stricken face gave Lepski cramps in his stomach. He hesitated, then snatched the receiver from Tanner’s hand.

“Carroll? I have been meaning to call, honey. Right now I’m up to my ears and over the top of my head! I’ll call you some time. Okay? . . . okay? I’ve got to go out right this second!”

“Lepski!”

The tone of his wife’s voice was like a bullet through Lepski’s brain.

He winced, then resigned himself.

“Yeah . . . yeah . . . how are you, baby? I’m rushing around like a goddamn . . . I mean, I’m busy, baby!”

“Lepski! Will you stop yammering and listen to me?”

Lepski leaned on Tanner’s desk and dragged his tie loose.

“I told you . . . I’m sorry. I have had only four hours’ sleep since I saw you. I . . . Goddamn it! I’m busy!”

“If I didn’t think for one moment that you were, are and we’ll be busy, Lepski, I would divorce you,” Carroll said. “Now will you stop sounding off and let me sound off?”

Lepski tried to make holes in the surface of Tanner’s desk with his fingers and nearly succeeded.

“I’m listening,” he said.

“I’ve just seen Mehitabel Bessinger.”

“Have you given away another bottle of my whisky?”

“Will you stop thinking about your drink. Mehitabel knew this Indian was the Executioner! She told me and I told you, but you wouldn’t listen! She . . .”

“Just a moment . . . did you give her a bottle of my goddamn whisky?”

“Lepski! How many more times do I have to ask you not to use vulgar language?”

The expression on Lepski’s face so startled Sergeant Tanner that he instinctively reached for the emergency Red Cross box.

“Yeah. So what did the old rum-dum foretell?”

“Don’t call her names like that. If I were you, I’d be ashamed to call an old woman a name like that.”

Lepski made a noise like a car with a flat battery trying to start.

“What was that?” Even Carroll who was used to the noises her husband made was startled. “Are you all right, Lepski?”

“I don’t know.”

“There are times when I get worried about you. You don’t seem to be able to concentrate and to become a sergeant you have to concentrate.”

Lepski wiped the sweat off his face.

“Yeah . . . you’re right. Go ahead . . . I’m concentrating.”

“Thank goodness! Mehitabel says . . . you’re sure you’re listening?”

Lepski stamped on his own foot with exasperation and hurt himself. As he began to hop up and down, Tanner who had never taken his eyes off Lepski, sat back stunned, his eyes goggling.

“Yes, I’m listening,” Lepski said, holding his foot in the air.

“She says you must look for the Executioner among oranges.”

“Among who?” Lepski shouted.

“Don’t shout like that: it’s vulgar. I said she said you should look for this man among oranges. She sees that in her crystal ball.”

“She does? Among oranges, huh?” Lepski drew in a breath that would have made a Hoover cleaner green with envy. Well, that’s something. She can’t go wrong with a give-out like that, can she? Let’s face it: the whole of this goddamn district is stinking with oranges. She’s on a winner there, isn’t she? For that, did she grab another bottle of my whisky?”

“I’m telling you what she said. She was right the first time, but you didn’t believe her. This is her second clue. Use your head, Lepski.”

“Okay, baby, I’ll use it. I’ve got to go now.”

“I’m trying to help you get promoted.”

“Sure . . . yeah . . . yeah . . . thanks!” He paused, then went on, “You didn’t answer my question. Did that old fruit vendor get another bottle of my whisky?”

There was a long pause, then Carroll said, her voice icy, “There are times, Lepski, when I think you have a tiny mind,” and she hung up.

Lepski replaced the receiver and stared at Tanner.

“Did your wife ever tell you you had a tiny mind, Charlie?”

Tanner gaped at him.

“Why should she? She wouldn’t know what the word means.”

“Yeah. You’re lucky,” and Lepski went down the stairs three at the time and threw himself into his car.

***

The hot evening sun beat down on the quay, bouncing off the striped awnings of the fruit stalls. The serious buying was over. A few stragglers, hoping to get cheap fruit, still moved around the stalls, but the main business of the day was over.

Jupiter Lucie had gone across to a nearby bar for a beer, leaving Poke in charge of the stall. They had had a good day and the stall had only a few boxes of oranges left.

Chuck came out of the shadows and paused by the stall. The two men looked at each other. The glittering black eyes of the Indian and Chuck’s small, uneasy eyes surveyed the quay, then Chuck moved forward.

“I got it: five hundred bucks!”

“Is she all right?”

Chuck nodded.

Poke began to weigh a pound of oranges, taking his time.

“She’ll be busy tomorrow , “ he said as he took an orange off the scales and looked for a smaller one. “Five calls.”

Chuck sucked in his breath.

“Five calls . . . five?”

“Two thousand five hundred dollars. I’ve put the dope how she’s to collect it at the bottom of the sack.”

Chuck nodded. Then he looked along the quay to right and left, then when he was satisfied no one was watching him, he slid something into Poke’s hand.

“I got it right: three fifty for you and a hundred and fifty for me?”

“Yes.”

Chuck picked up the sack of oranges and walked away.

After a while Luck came from the bar. He and Poke began to dismantle the stall.

Tomorrow would be another day.

***

When Captain Terrell drove into the forecourt of the Fifty Club he was lucky to spot Rodney Branzenstein getting out of his Rolls.

Branzenstein was one of the founder members of the Club. Apart from being a top class bridge player he was also a top class Corporation lawyer.

The two men shook hands.

“What are you doing here, Frank? Don’t tell me you’re joining this mausoleum?”

“I’m looking for information,” Terrell said.

“Couldn’t have come to a better man.” Branzenstein smiled. “Come in and have a drink.”

“I’d rather sit in your swank car and talk,” Terrell said. “It’s my bet this mausoleum as you call it could be a little sensitive to a police visit.”

“You could be right.” Branzenstein led the way to his car, opened the door and slid in.

“Nice car: television . . . phone . . . air conditioning . . . booze . . . some car,” Terrell said, as he settled himself beside Branzenstein.

“You know how it is . . . a status symbol. Between you and me, I’d rather drive an Avis,” Branzenstein said. “It’s part of the racket. What’s on your mind, Frank?”

Terrell told him.

“Poke Toholo? Yes, I remember him: good looking and mixed one of the best martinis in this City. The trouble, of course, was old mother Hansen couldn’t keep his hands to himself and the boy had to go.”

“I guessed that,” Terrell said. “How did the other members of the club react to him . . . apart from Hansen?”

Branzenstein shrugged.

“Ninety per cent of them don’t believe anyone who isn’t white isn’t a monkey. Personally, I like Seminole Indians. But the majority of the members of the club regard Indians as fetch-and-carry monkeys.”

“Did Toholo ever have trouble with Mrs. Dunc Browler?”

“Come to think of it, he did,” Branzenstein said, his eyes narrowing. “Of course she was a sad old bitch. All she thought about was her dog and bridge. I remember I was playing at another table.., this must be three months ago . . . could be more . . . I forget. Anyway, Toholo was serving drinks and Mrs. B. told him to take her dog out to have a pee. Toholo said he couldn’t leave the bar. I heard it all. Maybe he didn’t act servile as Mrs. B. expected. Anyway, she called him a nigger.”

“Then what happened?”

“The other three players with her told Toholo to take the dog out and not be insolent . . . so he took the dog out.”

“Who were the other players?”

“Riddle, McCuen and Jefferson Lacey.”

Terrell brooded.

“This makes a pattern, doesn’t it?” he said finally. “McCuen, Riddle and his mistress and Mrs. Browler are dead. I’d like to talk to Jefferson Lacey.”

Branzenstein nodded.

“Okay. He is one of our special members. He has a room at the club. Do you want me to introduce you?”

“That would be a help.”

But when Branzenstein asked the Hall porter if Mr. Lacey was available, he was told Mr. Lacey had gone out some thirty minutes ago.

Neither Branzenstein nor Terrell could guess that at this moment Jefferson Lacey, his face panic stricken, was fixing an envelope containing five one hundred dollar hills to the bottom of a coin box in a telephone booth in the lobby of the City’s railroad station.

***

Meg was beyond caring as she walked into the busy lobby of the Excelsior hotel that catered for second class tourists. The previous evening Chuck had told her she was to collect five envelopes from five different telephone booths the following morning.

“This is where we move into the money, baby,” Chuck had said. “This is when you make the big discovery. Do you know what that is?”

Meg sat on the bed, staring down at the worn carpet. She said nothing.

“Baby . . . have you wax in your ears?”

The threat in his voice forced her to look up.

“What discovery?” she asked indifferently.

Chuck nodded his approval.

“You make the discovery like this Columbus or whatever his name was . . .you’ve reached the promised land . . . a meal ticket.”

She looked beyond Chuck and through the open window at the sky with its pink clouds that were slowly turning to crimson as the sun began to set.

“Is that what you are?” she asked.

“Yeah. That’s what I am.” Chuck grinned. “Every doll in this goddamn world is looking for a meal ticket and you’ve hit the jackpot. You’ve found a meal ticket . . . me!”

Meg continued to stare at the clouds as they turned blood red in the dying rays of the sun.

“Is that what you call it? I take all the risks, give you the money and you call yourself a meal ticket?” she said.

Chuck lit another cigarette.

“The trouble with you is you have nothing between your ears except an empty hole. You’re lucky I have brains. Tomorrow, you go to five telephone booths and you pick up five hundred dollars from each booth. What does that add up to? Go on . . . tell me?”

“Who cares?” Meg said, shrugging. “Why bother me?”

Chuck’s hand flashed out.

Meg found herself lying flat on her back across the bed, her face stinging from the slap he had given her.

“You tell me,” he said viciously. “Make with the addition!”

She touched the side of her face as she stared up at him. The imprints of his fingers showed on her white cheek.

“I don’t know and I don’t care,” she said and closed her eyes. His second slap jolted her head.

“How much, baby?”

She lay there, waiting and shivering, her

eyes tightly closed.

“Okay, okay, if you’re that dumb!” Chuck said in disgust. “You know something? You bore me. You’ve got no ambition. Tomorrow, you’re picking up two thousand five hundred dollars? Do you hear? Two thousand five hundred dollars! Then you and me are getting the hell out of here! With that kind of money we’re fixed!”

She suddenly realised what he was saying and what it meant and she felt a tiny surge of hope.

“What about him?” she asked, opening her eyes.

“So you’ve got something between your ears after all.” Chuck wagged his head in mock admiration. “You know something? That’s the first bright thing you’ve said since I found you.”

Found me?

Meg stared up at the dirty ceiling. Found me . . . like a lost dog or a stray cat. Yes . . . that’s what she was . . . lost.

“Will you quit acting like a zombie and listen to me?” Chuck was saying It was good to lie flat on the bed, feeling the evening breeze coming through the open window on her hot, aching face. It required no effort.

Even having to listen to Chuck’s harsh voice required no effort.

“This Indian is crazy in the head . . . he’s a nutter,” Chuck went on. “I never told you, but he could have killed me. The first time . . . remember? When we went swimming.”

Why did he bother to tell her this now? she wondered. It was stale news.

She had already told him the Indian was sick.

“So he’s a nutter,” Chuck went on, “but he’s dreamed up an idea to get quick money and that’s what we want. That’s why I’m going along with him, but once we get the money . . . this two thousand five hundred bucks . . .we’re going to ditch him.”

Meg’s mind went back to her home. Suddenly and vividly, she saw her mother and father sitting in the shabby little living room watching the lighted screen of the television set. She could see her mother’s shapeless body slumped in the armchair. Her father had the habit of lifting his dentures with his tongue and settling them back into place with a distinct click. Her mother always kicked off her shoes when watching the telly: her feet were big and studded with corns.

“Baby!”

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

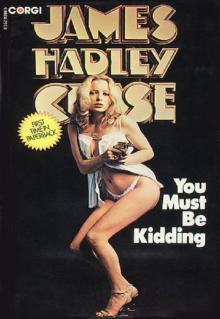

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

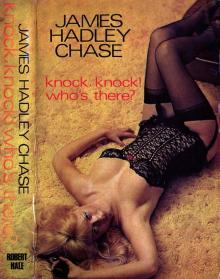

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

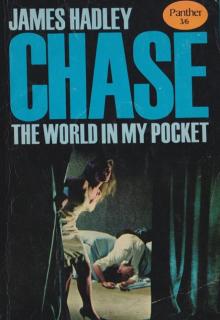

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

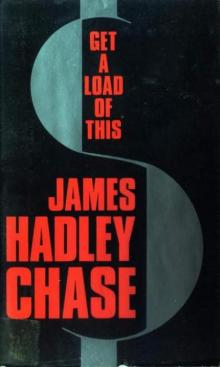

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

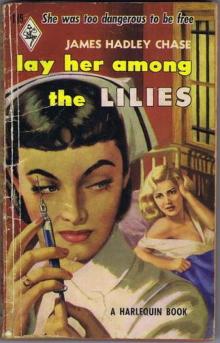

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

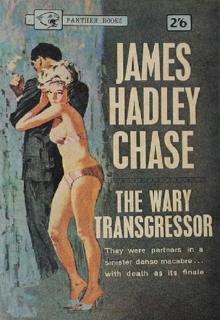

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

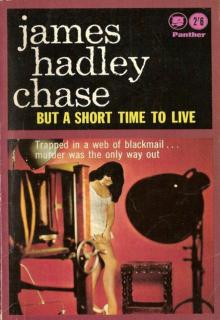

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail