- Home

- James Hadley Chase

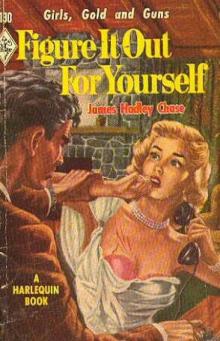

Figure it Out For Yourself Page 11

Figure it Out For Yourself Read online

Page 11

I picked on one who was on his own, aimlessly whittling a piece of wood into the shape of a boat.

'Can you put me on to Coral Row?'

He eyed me over, leaned away from me to spit into the oily water of the harbour and jerked his thumb over his shoulder in the direction of the coffee-shops, the sea-food stalls and the like that faced the waterfront.

'Behind Yate's Bar,' he said curtly.

Yate's Bar is a two-storey wooden building where, if you aren't fussy who you eat with, you can get a good clam-chowder and a ten-year-old ale that sneaks up on you if you don't watch out. I had been in there once or twice with Kerman. It's the kind of place where anything can happen, and very often does.

'Thanks,' I said, and crossed the broad water-front road to the bar.

Alongside the wooden building was an alley. High up on the wall was a notice that read: Leading to Coral Row.

I paused to light a cigarette while I regarded the alley with a certain amount of caution and no enthusiasm. The high walls blocked out the sunlight. The far end of the alley was a black patch of smelly air and suspicious silence.

I slid my hand inside my coat to reassure myself I could get the .38 out fast in case of an emergency, then I walked quietly towards the darkness.

At the end of the alley, and at a sharp right-angle to it, was Coral Row: a dismal, dark courtyard flanked on three sides by derelict-looking buildings that had at one time or another served as marine storehouses. By the look of them now they were nothing better than ratinfested ruins.

High above me I could see the stark, black roofs of the buildings sharply outlined against a patch of blue sky.

I stood in the opening of the alley, looking at the buildings, wondering if I was about to walk into a trap.

Opposite, a worm-eaten door sagged on one hinge. A dirty brass number, a 2, was screwed to the central panel.

There it was: 2 Coral Row. It now depended on myself whether I'd go in there or not. I took a drag at my cigarette while I looked the place over. It would probably be as dark as a Homburg hat inside, and I hadn't a flashlight. The boards would be rotten, and it would be impossible to move silently.

I decided to go ahead and see what happened.

Throwing my cigarette away, I walked across the courtyard to the sagging door. I wasn't any calmer than a hen chased by a motor car, and my heart was banging against my ribs but I went ahead because I'm a sucker for discipline, and I feel, every now and then, it is good for one's morale to do things like this.

I gum-shoed up the stone steps and peered into a long, dark passage. Facing me was a flight of stairs, several of them crushed flat as if some heavy foot had been too much for the wormrotten timber. There were no banisters, and the stains looked unpleasantly suicidal. I decided to leave them alone, and investigate the passage.

The floor creaked and groaned under my feet as I walked slowly and cautiously into the stalesmelling darkness. Ahead of me I heard a sudden rustle and a scamper of rats. The sound brought me to a standstill, and the hair at the back of my neck stiffened. To be on the safe side, and probably to bolster up my courage, I eased out my gun.

There was an open door at the end of the passage. I paused before it and peered in. There wasn't much to see except dark- ness. I was in no hurry to go in, and after a few seconds I made out tiny chinks of light coming in through the boarded walls. Even at that, it was much, much too dark in there.

I took a couple of very cautious steps forward, and paused just inside the doorway. There seemed no point in going far- ther, and no point in staying longer. If someone was hiding in there, I couldn't see him, and I doubted if he could see me, but in this I was wrong.

A board creaked suddenly close to me. The swish of a descending sap churned the air. I threw myself forward and sideways.

Something very hard and that hurt hit my shoulder, driving the gun out of my hand: a blow aimed at my head, and which would have sent me to sleep for a long, long time if it had landed.

I fell on my hands and knees. Legs brushed against my side, fingers groped up my arm, touched my face and shifted to my throat: lean, strong fingers, damp against my skin, and cold.

I shoved my chin into my collar so he couldn't get a prom grip, straightened, groped in my turn for a hold. My hand touched a coat, went up a powerful bicep. That gave me an idea where his face was. I slammed in a short, hard punch that connected with what felt like an ear.

There was a grunt, then a weight that could have been around fourteen stone dropped on top of me, driving me flat on to the floor. The fingers dug into my neck; hot, hurried breathing fanned my face.

But this time he wasn't dealing with a girl. Probably he hadn't had a great deal of trouble in handling Gracie, but he was going to have some trouble handling me.

I caught hold of his thumbs and bent them back. I heard him catch his breath in a gasp of pain. He jerked his thumbs out of my grip only because I let him, and as he straightened up I clouted him on the side of the head with a round-house swing that sent him away from me with a grunt of anguish.

I was half up, with my fingers touching the floor, as he launched himself at me again. I could just make out his dim form in the darkness as he came, and I lurched towards him. We met with a crash like a couple of charging bulls. He reeled back, and I socked him in the belly: a goingaway punch that hadn't the beef to put him down, but that brought the wind out of him like the hiss of a punctured tyre.

At the back of my mind I could see that screwed-up figure in the soiled blue nightdress hanging on the back of the bathroom door, and it made me mad. I kept moving in, belting him with right and left punches, not always landing, but taking good care when they did land they'd hurt. I took one bang on the side of the jaw that sent my head back, but it wasn't hard enough to stop me.

He was gasping for breath now, and backing away as fast as he could. I had to stop throwing punches, because I lost sight of him. I could only hear his heavy breathing, and guess he was somewhere just ahead of me. For a moment or so we stood in the darkness, trying to see each other, listening and watching for any sudden move.

I thought I could just make out a shadow in the darkness about a yard to my left, but I wasn't sure. I stamped my foot, and the shadow swerved away like a scared cat. Before he could cover his balance, I jumped in, and my fist caught him on the side of his neck. The impact sounded like a cleaver driving into a hunk of beef.

He gave a wheezing gasp, fell over on his back, scrambled up and backed away. He now seemed very anxious to break up the meeting and go home. I dived forward to finish him, in- stead, my foot landed on a rotten plank that gave under me and I came down with a crash that shook the breath out of me.

He had me cold then, but he wasn't interested. All he could think of was getting home.

He bolted for the door.

I struggled to get up, but my foot was firmly held in the rotten flooring. I caught a glimpse of a tall, broad-shouldered figure outlined in the dimness of the doorway; then it vanish-ed.

By the time I got my foot free I knew it would be useless to go after him. There were too many bolt-holes in Coral Gables to find him after such a start.

I limped to the door, swearing to myself. Something white lying in the passage caught my eye. I bent to pick it up.

It was a white felt hat.

III

The barman in Yate's Bar looked like a retired all-in-wrestler. He was getting old now, but he still looked tough enough to quell a riot.

He served me with a slice of baked ham between rye bread and a pint of beer, and while I ate he rested hairy arms on the counter and stared at me.

At this hour of the day the bar was slack. There were not more than half a dozen men at the various tables dotted around the room: fishermen and turtle men waiting for the tide to turn. They took no notice of me, but I seemed to fascinate the barman. His battle-scarred face was heavy with thought, and every now and then he passed a hand as big as a ham over his shaven head as if to coax h

is brain to work.

'Seen yuh kisser some place,' he said, pulling at a nose that had been stamped on in the past. 'Been in here before, ain't yu?'

He had a high, falsetto voice that would have embarrassed a choirboy.

I said I had been in before.

He nodded his shaven head, scratched where his ear had been, and showed a set of very white even teeth.

'Never forget a kisser. Yuh come in here fifty yars from now and I'd remember ya. Fact.'

I thought it wasn't likely either of us would live that long, but I didn't say so.

'Wonderful how some people remember faces,' I said. 'Wish I could. Meet a man one day, walk through him the next. Bad for business.'

'Yah,' the barman said. 'Guy came in yesterday; ain't been in here for three yars. Give him a pint of old ale before he could ask for it. Always drank old ale. That's memory.'

If he had served me old ale without asking me I wouldn't have argued with him. He didn't look as if he had a lot of patience with people who argued.

'Test your memory on this one,' I said. 'Tall, thin, broad-shouldered. Wears a fawn suit and a white felt hat. Seen him around here?'

The squat, heavy body stiffened. The battered, hairy face hardened.

'It ain't smart to ask questions in dis joint, brother,' he said, lowering his voice. 'If yuh don't want to lose yu front teeth, better keep yu yap shut.'

I drank some beer while I eyed him over the rim of the glass.

'That scarcely answers my question,' I said, put down the glass and produced a five-dollar bill. I kept it between my fingers so only he and I could see it.

He looked to right and left, frowned, hesitated, then looked to right and left again: as obvious as a ham actor playing Hard-iron, the spy, for the first time.

'Give me it wid a butt,' he said, without moving his lips.

I gave him a cigarette and the bill. Only five of the six men in the bar saw him take it. The other had his back turned.

'One of Barratt's boys,' he said. 'Keep clear of him: he's dangerous.'

'Yeah; and so's a mosquito if you let it bite you,' I said, and paid for the beer and the sandwich.

As he scooped up the money, I asked, 'What's he call himself?'

He looked at me, frowning, then moved off down to the far end of the bar. I waited a moment until I was sure he wasn't coming back, then I slid off the stool and went out into the hot afternoon sunshine.

Jeff Barratt: could be, I thought. I didn't know he had any boys. He had a good reason to shut Gracie's mouth. I began to wonder if he was the master-mind behind the kidnapping. It would fit together very well if he was; possibly too well.

I also wondered, as I walked across to where I had parked the Buick, if Mary Jerome was hooked up in some way with Barratt. It was time I did something about her. I decided to run up to the Acme Garage and ask some questions.

I drove fast up Beach Road into Hawthorne Avenue and I turned left into Foothill Boulevard.

The sun was strong, and I lowered the blue sunshield over the windshield. The sunlight, coming through the blue glass, filled the car with a soft, easy light and made me feel as if I was in an aquarium.

The Acme Garage stood at the corner of Foothill Boulevard and Hollywood Avenue, facing the desert. It wasn't anything to get excited about, and I wondered why Lute Ferris had selected such an isolated, out-of-the-way spot for a filling station.

There were six pumps, two air- and water-towers in a row before a large steel and corrugated shed that acted as a repair shop. To the right was a dilapidated rest-room and snack bar, and behind the shed, almost out of sight, was a squat, ugly looking bungalow with a flat roof.

At one time the station might have looked smart. You could still see signs of a blue-and-white check pattern on the build-ings, but the salt air, the sand from the desert, the winds and the rain had caught up with the smartness, and no one had bothered to take on an unequal battle.

Before one of the gas pumps was a low-slung Bentley coupé; black and glittering in the sunshine. At the far end of the ramp leading to the repair shop was a four-ton truck.

There seemed no one about, and I drove slowly up to one of the pumps and stopped; my bumpers about a couple of yard from the Bentley's rear.

I tapped on the horn and waited; using my eyes, seeing nothing to excite my interest.

After a while a boy in a blue, greasy overall came out of the repair shop as if he had the whole day still on his hands, and wasn't sure what he was going to do with it now he had it. He lounged past the Bentley, and raised eyebrows at me without any show of interest.

At a guess he was about sixteen, but old in sin and cunning. His oil-smudged face was thin and hard, and his small green eyes were shifty.

'Ten,' I said, took out a cigarette and lit it. 'Don't exhaust yourself. I don't have to be in bed until midnight.'

He gave me a cold, blank stare, and went around to the back of the car. I kept my eye on the spinning dial just to be sure he didn't short-change me.

After a while he reappeared and shoved out a grubby paw. I paid.

'Where's Ferris?'

The green eyes shifted to my face and away.

'Out of town.'

'When will he be back?'

'Dunno.'

'Mrs. Ferris about?'

'She's busy.'

I jerked my thumb towards the bungalow.

'In there?'

'Wherever she is, she's still busy,' the boy said and moved off.

I was about to yell after him when from behind the repair shop came a tall, immaculate figure in a light check lounge suit, a snap-brimmed brown hat well over one eye and a blood-red carnation in his buttonhole: Jeff Barratt.

I sat still and watched him, knowing he couldn't see me through the dark blue sunshield.

He gave the Buick a casual stare before climbing into the Bentley. He drove off towards Beechwood Avenue.

The boy had gone into the repair shop. I had an idea he was watching me, although I couldn't see him. I waited a moment or so, thinking. Was it a coincidence that Barratt had appeared here? I didn't think so. Then I remembered Mifflin had told me Lute Ferris was a suspected marijuana smuggler. I knew Barratt smoked the stuff. Was that the hook-up between them? Was it also a coincidence that Mary Jerome should have picked on his out-of-the-way garage from which to hire a car? Again I didn't think so. I suddenly realized I was making discoveries and progress for the first time since I started on this case. I decided to take a look at Mrs. Ferris.

I got out of the Buick, and set off along the concrete path that led past the repair shop to the bungalow.

The boy was standing in the shadows, just inside the door of repair shop. He stared at me woodenly as I passed. I stared right back at him.

He didn't move or say anything, so I went on, turned the comer of the shed and marched up the path to the bungalow.

There was a line of washed clothes across the unkept garden: a man's singlet, a woman's vest, socks, stockings and a pair of ancient dungarees. I ducked under the stockings, and rapped on the shabby, blistered front door.

There was a lengthy pause, and as I was going to rap again the door opened.

The girl who stood in the doorway was small and Compact and blowsy. Even at a guess I couldn't have put her age within five years either side of twenty-five. She looked as if life hadn't been fun for a long time; so long she had ceased to care about fun, anyway. Her badly bleached hair was stringy and limp. Her face was puffy and her eyes red with recent weeping. Only the cold, hard set to her mouth showed she had a little spirit left, not much, but enough.

'Yes?' She looked at me suspiciously. 'What do you want?'

I tipped my hat at her.

'Mr. Ferris in?'

'No. Who wants him?'

'I understand he rented a car to Miss Jerome. I wanted to talk to him about her.'

She took a slow step back and her hand moved up to rest on the doorknob. In a second or so she was going to slam the door

in my face.

'He's not here, and I've nothing to tell you.'

'I've been authorized to pay for any information I get,' I said hurriedly as the door began to move.

'How much?'

She was looking now like a hungry dog looking at a bone.

'Depends on what I get. I might spring a hundred bucks.'

The tip of a whitish tongue ran the length of her lips.

'What sort of information?'

'Could I step inside? I won't keep you long.'

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

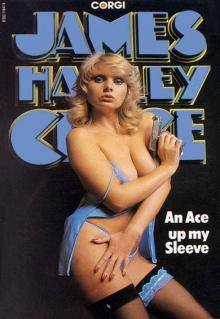

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

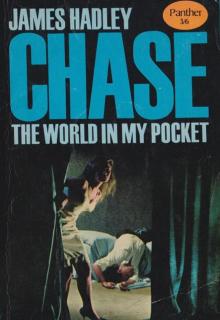

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

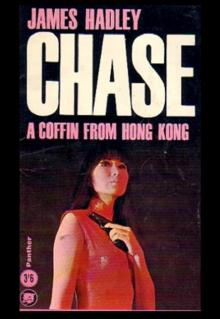

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

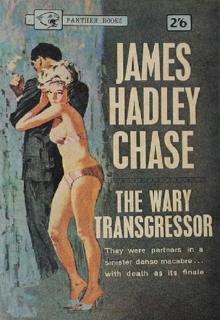

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

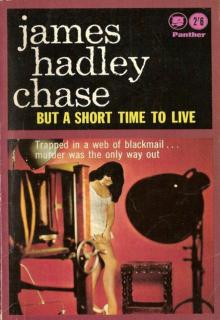

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

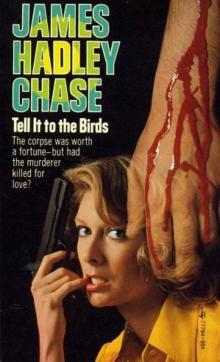

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

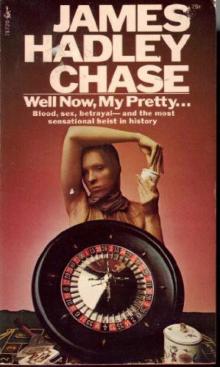

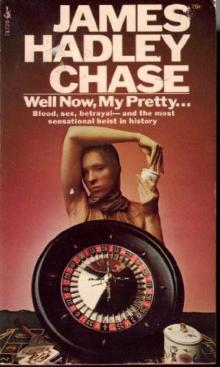

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

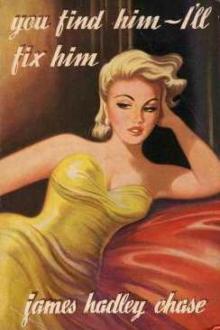

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

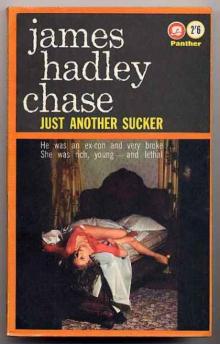

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

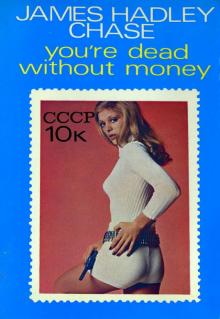

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

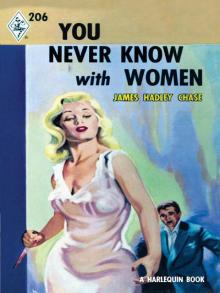

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

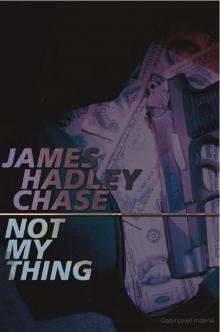

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

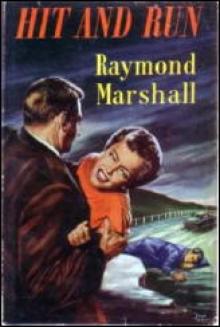

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

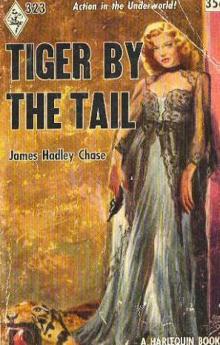

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail