- Home

- James Hadley Chase

You've Got It Coming Page 11

You've Got It Coming Read online

Page 11

“Don't lose your nerve, Harry,” she said. “It's done now.”

“Oh, shut up!” Harry snarled. “You can talk. You aren't heading for the chair. That was a fine idea of yours, dreaming up Harry Green. If you're all that smart, why didn't you think of my prints? Harry Green doesn't exist! Like hell he does! He's here —right here for any cop to find,” and he held out his hands towards her. “If you hadn't sold me on the idea of disguising myself I wouldn't have pulled the job!”

Glorie closed her eyes.

“How can you talk like that, Harry? You know I tried and tried to stop you. . .”

“Stop talking! That's all you can do—talk! You've never stopped talking since we've been together. How the hell am I going to get out of this jam?”

The sound of a car engine drew him back to the window. A breakdown track had arrived. The police hooked the Pontiac to the crane and the truck took the Pontiac away.

The three detectives stood in a group, talking. Harry watched them, his breath whistling through his clenched teeth. After a while, the detectives walked over to their car, got in and drove away. The policemen hung around a little longer, then they too got in their cars and drove away.

Harry stepped back and moved slowly to the bed and sat on it. He put his face in his hands. He hadn't realized until this moment just how frightened he had been. The reaction knocked him off balance.

Glorie ran into the other room, poured a stiff whisky and came back with it.

“Drink this, darling.”

Harry gulped down the whisky, shuddered and put down the glass.

“I can't believe it,” he muttered. “To think those punks had me cold, and they didn't do anything about it. They had me! They had only to take my prints and I was sunk.”

“Why should they?” Glorie said. “They can't take everyone's prints. Why should they think you were Harry Green?”

“Yeah, that's right. He looked at her, then reached out and pulled her down beside him. “I didn't mean what I said just now, baby. You know that, don't you? I was scared. I didn't know what I was saying. I'm sorry, Glorie, honest, I'm sorry.”

“It's all right. I know how you felt. I was scared too. Oh, darling, let's stop this before it's too late. We can mail the diamonds to Ben and then we're free of them. Let’s do it first thing in the morning. If s the only way. Please, Harry.”

He pulled away from her, got up and went over to the table and poured himself another drink.

“No. I got away with it, didn't I? I'd be a mug to pass up a million and a half bucks: that's what I should get for them. Think of it! Think what we can do with that much money. I'm going ahead with this and no one's going to stop me.”

She made a little movement of despair, then shrugged her shoulders.

“Oh, all right, Harry: just as you say.”

II

The Far Eastern Trading Corporation had offices that spread over four floors of the National and Californian State Building on 27th Street.

The smartly-dressed, well-groomed girl at the reception desk looked at Harry with a kindly, patronizing smile that is usually reserved for simple-minded children when they have asked for the impossible.

“No, I'm sorry, Mr. Griffin, but Mr. Takamori never sees anyone except by appointment,” she said. “Perhaps Mr. Ludwig could help you? I'll see if he is disengaged.”

“I don't want Mr. Ludwig,” Harry said. “I want Mr. Takamori.”

“I'm sorry but that is quite impossible.” The kindly smile began to fade. “Mr. Takamori . . .”

“I heard you the first time,” Harry said, “but he'll see me.”

He took a sealed envelope from his pocket and handed it to the girl. “Give him that. You'll be surprised how anxious he'll be to have me walk in.”

She hesitated, then, lifting her shoulders, she touched a bell push. A small , boy in a fawn uniform with blue facings materialized from a nearby room and came to the desk.

“Give this note to Miss Schofield,” the girl said. “It's for Mr. Takamori.” As the boy went away, he went on to Harry, “Please sit down. Miss Schofield may be able to see you.”

Harry sat down, took out a cigarette and lit it. He was hot and nervous and jittery, but he managed not to show it.

It was now five days since the robbery. He and Glorie had been living in a small hotel in New York. He had left her there while he had returned to Los Angeles for this all-important interview with Takamori.

He had racked his brains for a safe method of dealing with Takamori, but without success. It had slowly and reluctantly dawned on him that if he were to get his hands on a million and a half dollars, he had to approach Takamori as himself, and not to attempt to go to him under a false name or in disguise.

That amount of money couldn’t be hidden. Even if he spread the amount over a dozen banks, he still couldn’t hide it. He would get into trouble with the tax people, and then the police would get after him. He had no alternative but to deal openly with Takamori. He had to gamble on Takamori wanting the diamonds so badly that he would be prepared to work with Harry and not with the police. If the gamble didn't come off, then Harry would be in trouble, but the way he was planning it, he wouldn't be in serious trouble and he felt the risk was worth it.

But Glorie had been horrified when Harry had outlined his plan to her. She had begged him not to go ahead with it. By now, Harry was getting tired of her opposition, and he had curtly told her not to interfere. Okay, he admitted it: it was a risk, but what did she expect if they were going to make that kind of money?

He sat in the deep armchair, his feet resting on the thick pile of the carpet and waited. There was a constant stream of men with brief cases coming to the desk. The girl handled them with the kindly, patronizing smile that made Harry itch to smack her.

She passed them on to various small boys who took them away down the corridor and out of Harry's sight. Still he sat there, smoking.

Thirty-five minutes and four cigarettes later, the boy who had taken his note came down the long corridor and went over to the girl at the reception desk. He said something to her, and Harry, who was watching her, saw her eyebrows shoot up.

“It's okay for you to see Mr. Takamori,” she said and smiled.

The smile was no longer patronizing. She was friendly and startled.

“I told you, didn't I?” Harry said and went after the boy who took him to a small elevator, whisked him up three floors, then conducted him down a passage to a solid walnut door before which the boy paused. He seemed to be gathering his strength and courage before he knocked. When he had knocked, a faint sound came from beyond the door. The boy turned the handle and let the door swing open. He stood aside, and Harry walked into a vast, luxurious office, panelled with polished walnut. He felt the pile of the carpet tickling his ankles as he crossed the room to the big desk behind a huge window that looked out on the east side of Los Angeles.

At the desk sat a little yellow man in a black coat and black-and-white check trousers, his greying hair slicked down, his small, compact face as expressionless as a hole in a wall.

He looked at Harry and waved a small, perfectly groomed hand towards a chair by the desk. Harry sat down, put his hat on the floor beside him, and blew a cloud of cigarette smoke towards the ceiling.

“It is Mr. Griffin—Harry Griffin?” the little man at the desk said, looking at Harry with bright, bird-like eyes.

“That's right,” Harry said. “You are Mr. Takamori?”

The little man nodded, reached out his hand and picked up Harry's note.

“You say here that you want to talk to me about diamonds. He dropped the note on his desk and sat back, folding his hands on the snowy white blotter. “What do you know about diamonds, Mr. Griffin?”

“Nothing,” Harry said. “I happened to see in the newspaper a few days ago that you had persuaded the U.S. Consulate to allow you to export three million dollars’ worth of diamonds. The following morning I saw in the paper that the diamonds h

ad been stolen. I thought you might be interested in getting them back.”

Takamori looked thoughtfully at him.

“Yes, I should be interested,” he said.

“I thought you would be.” Harry paused to flick ash off his cigarette, then he went on. “A day after the robbery, I happened to be driving to Sky Ranch airport on business and about two miles from the scene of the robbery I got a flat. I fixed it. I had some sandwiches with me and I thought I might just as well have lunch as I had stopped as to wait until I reached the airport. I went over to a sandhill and sat down. Half hidden in the sand was a square-shaped steel box. I had a little trouble in opening it as it was locked, but I got it open after a while. It was full of diamonds. There was also an invoice in the box that told me the diamonds came from the Far Eastern Trading Corporation and I realized they were the stolen diamonds. From the way the box was lying, it seems likely the thieves lost their nerve and threw the box out of the car window. I was going to hand the diamonds to the police, but the idea came to me that you and I might do a deal.”

Takamori leaned forward to stare at Harry.

“You actually have the diamonds?” he asked. His voice was as unexcited as if he were asking Harry the time of day.

“I actually have them,” Harry said.

Takamori sat back. He rubbed the side of his small, yellow nose with the forefinger of his right hand.

“I see,” he said, “and you thought you and I might do a deal. That is interesting. What kind of a deal had you in mind, Mr. Griffin?”

Harry stretched out his long legs. He stubbed out his cigarette in the crystal glass bowl on the occasional table at his side. He took another cigarette from his case and lit it. All the time he was doing this he stared into the dark, glittering eyes of Takamori.

“A business deal,” he said. “It seems to me—and correct me if I am wrong—that when someone has something that another party wants very badly, the someone would be a mug to hand it over for nothing.”

Takamori picked up a paper knife and examined it as if he had never seen it before.

“That is the basis of business, Mr. Griffin,” he said mildly, “but I understand in this country such a formula does not apply when dealing with stolen property. I understand it is not only the duty but the obligation of the finder to return what he has found and accept the reward. Is that not so?”

Harry smiled. He was feeling more at ease now, but he wasn't fooled by Takamori's mild manner.

“I guess that's right,” he said, “but I had another angle on this particular setup. I understand these diamonds are insured and that the brokers are covering you.”

“The brokers will cover me, Mr. Griffin, when they are quite sure the diamonds are not going to be recovered.”

“Yeah, that's the usual way the brokers work. They keep you waiting for your money, but that shouldn't bother you. From what I hear you have a lot of money, but what you haven t got is recognition and honours from your government. I’ve been digging into your background. It seems you've done quite a lot of good work for your country without much reward.”

Takamori laid down the paper knife “Should we keep to the point, Mr. Griffin?” he said, a slight rasp in his voice. “You were talking about finding the diamonds. I take it you propose to sell them to me.”

Harry leaned back in his chair.

“That's the idea.”

“And how much would you want for them?

“It's not as easy as that,” Harry said. “Taking cash presents difficulties. I want you to finance an idea of mine. It would be less tricky for me to make an arrangement like that.”

Takamori went back to his inspection of the paper knife.

“What would the amount involve, Mr. Griffin, always supposing the arrangement interested me?”

“It would run out at about a million and a half. The way I’ve planned it I couldn't take less.”

“That is a lot of money,” Takamori said, testing the point of the paper knife on the ball of his thumb. He seemed to find it sharp for he frowned and examined his thumb to see if he had drawn blood: he hadn't. “It has occurred to you, Mr. Griffin, that Chief of Police O'Harridan could not only persuade you to hand over the diamonds for nothing, but even arrange for you to remain in prison for some considerable time.”

Harry shrugged.

“He wouldn't persuade me to hand over the diamonds. I have them in a place where they won't be found. I agree he might be able to put me in prison, but I doubt it. It would be your word against mine, wouldn't it?”

“Not entirely,” Takamori said. “This conversation is being recorded on a tape machine. I have only to hand the tape to O'Harridan and he would have no difficulty in prosecuting you.”

Glorie had warned Harry that the conversation might be recorded and he had laughed at her. Now he knew she was right, he still wasn't flustered.

“Okay,” he said, leaning forward, “you have enough on your recorder to put me in prison. I admit it. Now suppose you turn it off so we can talk off the record. If my proposition doesn't suit you, send for the police, but at least listen to what I have to say. I'm not talking until you turn the recorder off.”

Takamori laid down the paper knife, again scratched his nose with the forefinger of his right hand, then he leaned forward and pressed down a button on his desk.

“The recorder is now no longer working, Mr. Griffin. What is your proposal?”

“Mind if I convince myself that it isn't working?”

Takamori opened a drawer in his desk.

“By all means.”

Harry got up, peered at the recorder, nodded and sat down again.

“Right. Now let's talk business. You have taken eighteen months to collect the diamonds and to get permission to export them. For this you are being received by your Emperor and he will honour you. I was in Japan, Mr. Takamori, during the war. I know a little of the background of your race, and I know you prize an audience with your Emperor pretty highly. You won't get the audience if you don't produce the diamonds. Okay, you can sick the cops on to me, but if you do, you'll never get the diamonds. There are plenty of other guys who can handle the diamonds and will be glad to take them off me. I had nothing to do with the robbery. My crime is finding the diamonds and asking money for them: that'll rate about three years; maybe if I come up against a tough judge, I'll draw five. I'm twenty-eight. In five years' time I shall be thirty-three, still young enough to enjoy the money I shall get for the diamonds when I sell them. In five years' time you'll be around seventy-three: you won't have all that time to enjoy an honour your Emperor may or may not give you if you dig up another batch of diamonds if—repeat if—the authorities here let you export them which I can't see them doing.” He stubbed out his cigarette and lit another while he stared at the expressionless, yellow face. “Rather than disappoint your Emperor and lose face, rather than wait to see if you can dig up another batch of diamonds, I think you'd be smart to deal with me. The way I see it, you will not only have the diamonds and your honour, but you will also clean up a profit of a million and a half bucks, and that sounds a pretty sound proposition to me.”

Takamori leaned back in his chair, his black, glistening eves resting on Harry's face.

“You have a persuasive manner, Mr. Griffin. How do you suggest I should make a profit on the deal?”

“It's obvious, isn't it? The diamonds are insured. The brokers eventually will pay up in full. You will get three million bucks within a year. You will have the diamonds. You don't have to tell the brokers you have got them back. You will finance my company for a million and a half and the other million and a half goes into your pocket. Simple, isn't it?”

“It would appear so,” Takamori said. “What is this company you suggest I finance?”

“I want to start an air-taxi service. I have all the dope here.”

Harry took out a bulky envelope from his pocket and put it on the desk. “I'll leave this with you. You will want to study it. You

can have a ten percent share in the business if it interests you. I'll make it pay. You don't have to worry about that. All I want is the capital, and that's what you've got. I don't expect an immediate decision, but for your own sake, don't take too long to make up your mind.” He got to his feet. “It may occur to you that, if you go ahead with this deal, you will be making yourself a first-rate target for blackmail. Maybe you are, but so am I. This is a partnership: if either member of the partnership tries to double cross the other, there is a blow back to the double crosser. It's not as if I'm going to disappear. If you finance me I'll have a business to look after, and you can always find me. To a certain extent we'll have to trust each other. I could go to jail for finding the diamonds; you could go to jail for twisting the insurance companies. Think it over. I'll be back at this time on Thursday. That'll give you forty-eight hours in which to decide. I'm taking a chance on you. For all I know the police will be waiting for me when I come back. I'm risking that. It they are here then you can kiss the diamonds good-bye.”

Leaving Takamori fiddling with the paper knife, Harry crossed the room, opened the door and let himself out.

When he reached the main lobby, the girl at the reception desk came to meet him.

“Excuse me, Mr. Griffin, Mr. Takamori just phoned through. You haven't left him your address.”

Harry hesitated. Was Takamori going to slick the cops on to him: have him arrested? If that was his intention he could do it when Harry called on him.

“I'm at the Ritz, room 257,” Harry said.

“Thank you, Mr. Griffin. I'll tell Mr. Takamori.”

III

Borg moved ponderously across the room and settled his vast bulk in the armchair facing Ben Delaney's desk. He pushed his black slouch hat to the back of his head, and taking out a dirty handkerchief, he wiped his forehead while he breathed asthmatically, his great chest heaving as he struggled to get more air into his lungs.

“Now look, Borg,” Ben said, resting his hands on his blotter and leaning forward, “forget what I said on the telephone the other night. I was rattled. Okay, so I've been taken for a ride. I've lost fifty grand. Sooner or later anyone with dough gets taken: I don't care who it is. I've decided to write it off to experience. Even if I got the diamonds now, they'd be too hot to handle. O'Harridan is really working on this thing. I'd have to sit on those rocks for five or six years and even then I'd be sticking my neck out. Killing the guard fixed it, and to make matters worse, one of the passengers on the aircraft was a senator, and he's really riding O'Harridan ragged.”

Come Easy, Go Easy

Come Easy, Go Easy Why Pick On ME?

Why Pick On ME? The Dead Stay Dumb

The Dead Stay Dumb Figure it Out For Yourself

Figure it Out For Yourself 1944 - Just the Way It Is

1944 - Just the Way It Is No Business Of Mine

No Business Of Mine 1953 - The Sucker Punch

1953 - The Sucker Punch Cade

Cade 1973 - Have a Change of Scene

1973 - Have a Change of Scene An Ace up my Sleeve

An Ace up my Sleeve 1968-An Ear to the Ground

1968-An Ear to the Ground 1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself

1950 - Figure it Out for Yourself 1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead

1976 - Do Me a Favour Drop Dead The Flesh of The Orchid

The Flesh of The Orchid 1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place

1974 - Goldfish Have No Hiding Place Whiff of Money

Whiff of Money 1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts

1984 - Hit Them Where it Hurts 1971 - Want to Stay Alive

1971 - Want to Stay Alive 1980 - You Can Say That Again

1980 - You Can Say That Again 1978 - Consider Yourself Dead

1978 - Consider Yourself Dead The Paw in The Bottle

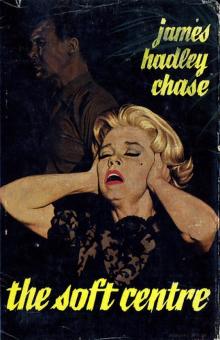

The Paw in The Bottle Soft Centre

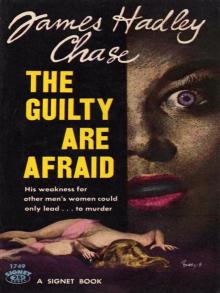

Soft Centre The Guilty Are Afraid

The Guilty Are Afraid The Soft Centre

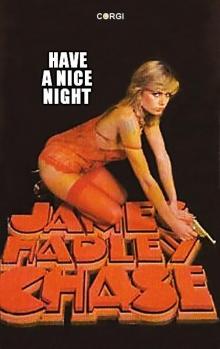

The Soft Centre Have a Nice Night

Have a Nice Night 1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid

1957 - The Guilty Are Afraid 1979 - You Must Be Kidding

1979 - You Must Be Kidding Knock, Knock! Who's There?

Knock, Knock! Who's There? 1958 - The World in My Pocket

1958 - The World in My Pocket Get a Load of This

Get a Load of This 1958 - Not Safe to be Free

1958 - Not Safe to be Free This Way for a Shroud

This Way for a Shroud More Deadly Than the Male

More Deadly Than the Male Safer Dead

Safer Dead 1945 - Blonde's Requiem

1945 - Blonde's Requiem I'll Bury My Dead

I'll Bury My Dead 1975 - The Joker in the Pack

1975 - The Joker in the Pack 1972 - Just a Matter of Time

1972 - Just a Matter of Time 1954 - Mission to Venice

1954 - Mission to Venice Strictly for Cash

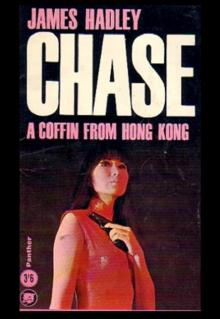

Strictly for Cash A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG

A COFFIN FROM HONG KONG Lady—Here's Your Wreath

Lady—Here's Your Wreath I Would Rather Stay Poor

I Would Rather Stay Poor Eve

Eve Vulture Is a Patient Bird

Vulture Is a Patient Bird 1979 - A Can of Worms

1979 - A Can of Worms 1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead

1949 - You're Lonely When You Dead 1965 - This is for Real

1965 - This is for Real (1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief

(1941) Miss Callaghan Comes To Grief What`s Better Than Money

What`s Better Than Money This is For Real

This is For Real Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2

Lay Her Among the Lilies vm-2 Knock Knock Whos There

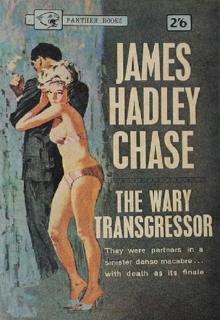

Knock Knock Whos There 1952 - The Wary Transgressor

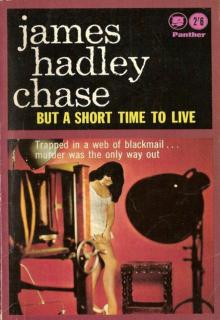

1952 - The Wary Transgressor 1951 - But a Short Time to Live

1951 - But a Short Time to Live 1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong

1962 - A Coffin From Hong Kong Tell It to the Birds

Tell It to the Birds Well Now, My Pretty…

Well Now, My Pretty… The World in My Pocket

The World in My Pocket A Lotus for Miss Quon

A Lotus for Miss Quon You Find Him, I'll Fix Him

You Find Him, I'll Fix Him Lay Her Among The Lilies

Lay Her Among The Lilies 1951 - In a Vain Shadow

1951 - In a Vain Shadow Miss Shumway Waves a Wand

Miss Shumway Waves a Wand 1953 - This Way for a Shroud

1953 - This Way for a Shroud 1964 - The Soft Centre

1964 - The Soft Centre You Can Say That Again

You Can Say That Again 1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything

1975 - Believe This You'll Believe Anything 1954 - Safer Dead

1954 - Safer Dead 1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy

1960 - Come Easy, Go Easy Shock Treatment

Shock Treatment 1953 - I'll Bury My Dead

1953 - I'll Bury My Dead You Find Him – I'll Fix Him

You Find Him – I'll Fix Him Dead Stay Dumb

Dead Stay Dumb Just Another Sucker

Just Another Sucker Well Now My Pretty

Well Now My Pretty You've Got It Coming

You've Got It Coming 1972 - You're Dead Without Money

1972 - You're Dead Without Money 1955 - You Never Know With Women

1955 - You Never Know With Women Not My Thing

Not My Thing Hit and Run

Hit and Run 1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve

1971 - An Ace Up My Sleeve 1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway

1970 - There's a Hippie on the Highway 1968 - An Ear to the Ground

1968 - An Ear to the Ground 1955 - You've Got It Coming

1955 - You've Got It Coming 1963 - One Bright Summer Morning

1963 - One Bright Summer Morning 1967 - Have This One on Me

1967 - Have This One on Me He Won't Need It Now

He Won't Need It Now 1953 - The Things Men Do

1953 - The Things Men Do Believed Violent

Believed Violent You Never Know With Women

You Never Know With Women Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief

Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief Mission to Siena

Mission to Siena What's Better Than Money

What's Better Than Money Trusted Like The Fox

Trusted Like The Fox I'll Get You for This

I'll Get You for This Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3

Figure It Out for Yourself vm-3 Like a Hole in the Head

Like a Hole in the Head 1977 - I Hold the Four Aces

1977 - I Hold the Four Aces 1969 - The Whiff of Money

1969 - The Whiff of Money 1946 - More Deadly than the Male

1946 - More Deadly than the Male 1956 - There's Always a Price Tag

1956 - There's Always a Price Tag No Orchids for Miss Blandish

No Orchids for Miss Blandish 1977 - My Laugh Comes Last

1977 - My Laugh Comes Last 1958 - Hit and Run

1958 - Hit and Run 1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf

1981 - Hand Me a Fig Leaf 1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal

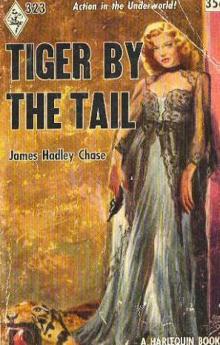

1966 - You Have Yourself a Deal Tiger by the Tail

Tiger by the Tail